William Gibson and his novel Neuromancer burst into the cultural consciousness in 1984. The book was in the first wave of cyberpunk and established ideas of cyberspace, artificial intelligence, and human augmentation that only to become more relevant with each passing year. His more recent work has examined everything from online message boards, viral marketing, and corporate terrorism.

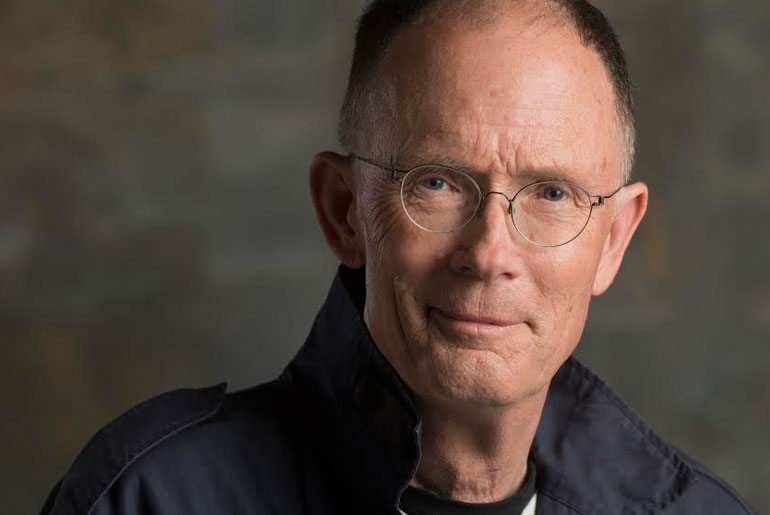

It might seem odd to interview a science fiction author on a website that’s explicitly about blue jeans, but not every science fiction author has a capsule collection with Buzz Rickson’s. If Mr. Gibson knows anything as well as writing novels it’s clothing–specifically repro workwear, military wear, and technical streetwear (note the Acronym he’s wearing above).

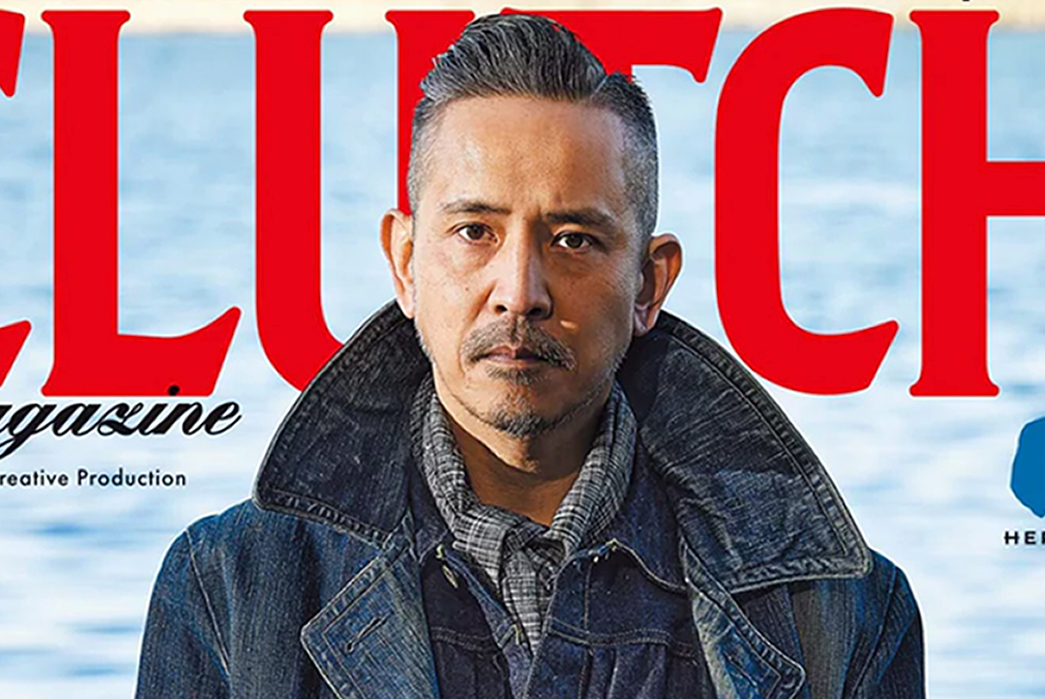

In 2004 he launched a joint collection with the Japanese repro label of mil-spec jackets. They began with a black MA-1 and have slowly grown the line into several dozen flying jackets, deck jackets, and accessories. We recently connected with Mr. Gibson and discussed everything including the start of his collaboration with Rickson’s, his time as a vintage picker, and how the internet has changed the nature of fashion.

Heddels (David Shuck): The Buzz Rickson William Gibson Collection has been around since 2004 so it predates all of the North American retail stores and most of the English-language message boards. If not in store or online, what was your introduction to Japanese repro clothing?

William Gibson: In 2001, I was writing a novel called Pattern Recognition. The protagonist was an American woman famous for the minimalism of her style. An internet buddy of mine in Seoul happened to visit Tokyo then, and told me he’d been able to buy a reproduction military jacket there, by a company called Buzz Rickson. He was excited about it, said their stuff was exquisitely made, hard to get. He had a pal at work who collected nothing but vintage US military *zippers*.

These guys had an otaku thing going on like nobody’s business. It was an N-1 deck jacket. I thought that the brand sounded right for my heroine, and I liked the idea of a passionate Japanese reproduction of an old US military garment, though at the time it was just an idea, because I’d never seen anything quite like that, though I’d been to Tokyo a few times. So I invented a jacket for her, but I made it a black MA-1, because I like MA-1s on women, and because she had a very limited color-range.

As it it happened, when the book was published in the UK, I was in London, found Buzz Rickson heritage jeans in American Classics, by Covent Garden, great old “ authenticity” shop. and bought some. So that was my rediscovery of rigid denim, overlapping my discovery of Buzz Rickson. I started buying LVC denim on eBay, when it was being designed in Tokyo but still made in their Valencia Street factory.

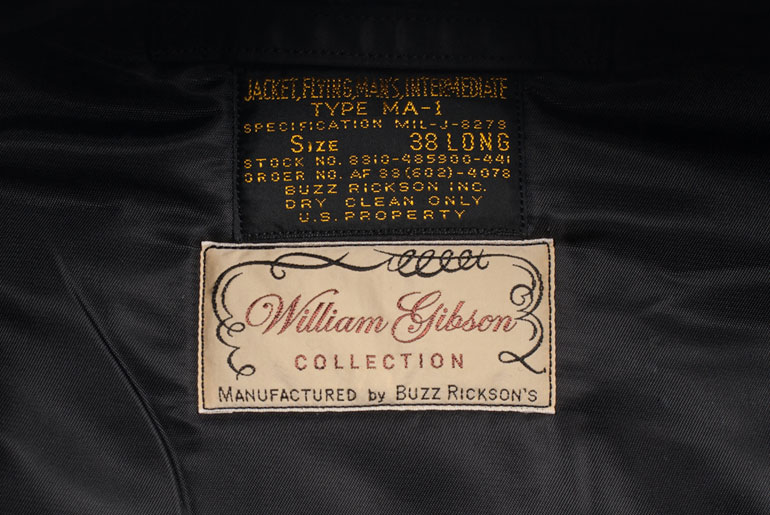

Eventually I received a baffled letter from Buzz Rickson, asking why I’d put their name on something they’d never made. I explained it as best I could, apologetically, and they told they really wanted to make that jacket. They’d been getting letters from people, asking where they could buy one. So the black MA-1 was our first jacket. I had them make it a few inches longer than the original pattern, though, because most MA-1s are a little too short for me.

The William Gibson Collection MA-1. Image via: Self Edge.

H: What’s the process like in producing the collection?

WG: Most of the garments are US military patterns, full spec, but black. The fabrics are woven for the particular garment, in Japan, so the black nylon for the MA-1 and N-3B is custom-made. I make suggestions. My first, actually, was for a black N-1.

Another year I suggested they make chinos out of the black bedford cord they’d had woven for the shell of our N-1. I love those, but I actually prefer the black straight-leg five-pocket jeans that Self Edge had Sugar Cane (one of Buzz Rickson’s sister labels) make out of the same fabric. I really enjoy the process, such as it is. It’s as if I get to pretend for a few days that I’m Hiroshi Fujiwara, though they won’t always make what I ask for.

H: What do you think of American influence on Japanese fashions? I’ve always struggled with the fact that one of the most prized vintage items in Japan are A-2 jackets, the very jackets of the men who bombed them. Why have the American military and workwear aesthetics of the 40s, 50s, and 60s become such popular subcultures in Japan?

WG: Japan had a more radical experience of future shock than any other nation in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. They were this feudal place, locked in the past, but then they bought the whole Industrial Revolution kit from England, blew their cultural brains out with it, became the first industrialized Asian nation, tried to take over their side of the world, got nuked by the United States for their trouble, and discovered Steve McQueen! Their take on iconic menswear emerges from that matrix. Complicated!

H: Much of your work, particularly the Sprawl trilogy, explores the expanding influence of Japanese culture on the rest of the world. Do you think your predictions have become manifest? Has Japanese obsession with Americana has in turn affected the fashions of the United States?

WG: When I was first writing about Japan, it was at the peak of the Bubble. Bubble popped, but they kept on going. Japanese street style feeds American iconics back into America in somewhat the way English rock once fed American blues back into America.

H: To a certain extent, many of the items made by brands like The Real McCoy’s, Buzz Rickson’s, and Levi’s Vintage Clothing are knockoffs that happen to be better made than the genuine articles. Would you consider such items to be simulacra of the originals? Can a repro ever be anything more than a very well made copy?

WG: “Authenticity” doesn’t mean much to me. I just want “good”, in the sense of well-designed, well-constructed, long-lasting garments. My interest in military clothing stems from that. It’s not about macho, playing soldiers, anything militaristic. It’s the functionality, the design-solutions, the durability. Likewise workwear.

Military clothing is built to strict contract, but with the manufacturer cutting ever corner they can without violating the specifications. The finishing on a Rickson reproduction is exponentially superior to the finishing on most of the originals, and I’d much rather have a brand-new exact copy that’s more carefully assembled.

A reproduction A-2 Flying Jacket from The Real McCoy’s. Image via: Blue in Green.

H: The heritage/workwear movement of the last five-ish years mostly harkens back to the blue collar styles of the early to mid-twentieth century. One of the main buzzwords is “authenticity”–it was more authentic when people worked with their hands, products were made in the US, etc. Many companies go to extreme lengths to recreate the products that are supposedly authentic to that era–buttons, fabrics, zippers, stitches.

What fallacies do you see in this selective view of the past? Is this a reactionary and regressive movement? Are we no different than the Amish but focused on a different era?

WG: The difference between, say, Engineered Garments and, for instance, Iron Heart, is that Engineered Garments is nostalgic, while Iron Heart is atemporal. Iron Heart achieves that atemporality through an inherent tightness, a stubbornness of intent. Iron Heart clothes look brand new when you buy them. Hard, bright. Which was how real vintage looked when it was new. Like you could cut yourself on them. Then you wear them for five years and very gradually they change. Compared to that, Engineered Garments feels slightly pre-digested to me. Though to be fair, J.Crew makes Engineered Garments look like Iron Heart! I actually like Engineered Garments, the idea of it.

With J.Crew, say, or Urban Outfitters, claims to authenticity tangle bizarrely with economies of scale, and we see “value-mining”, hollowing out the individual unit for maximum profit. T-shirt weaves conceived to require less cotton (“it looks authentically worn”). That’s when you get into seriously sad simulacra territory.

An Iron Heart chambray shirt (left) and a J.Crew chambray shirt (right).

H: What do you think of Needles and the way they frankenstein old clothes into new garments?

WG: I don’t think they have any grasp of source code at all. Their combination MA-1/M-65 field jacket actually negates the functionality of the M-65’s lower pockets. You can’t fucking put your hands in them. Freaks me out.

Needles M-65/MA-1 Rebuild. Image via: The Bureau Belfast.

This stuff [the Victorinox Remade in Switzerland Collection], which I deeply regret having been unable to get at the time, is among the best upcycling of surplus garments I’ve seen.

Other best bits have all been from Portobello or Camden stalls, anonymous, made from WWII bivouac tents, plus some Berlin efforts, similar. And a take on the Levi’s trucker jacket that Monitaly cut from US surplus tents. Sorry I missed that one as well.

H: The clothing inspired by this period is often so expensive that the vast majority of consumers will never use these clothes for their intended purpose, manual labor. What’s the appeal? Why do we spend lots of money to dress like poor people from a hundred years ago?

WG: I don’t know about 1915, but in 1947 a lot of American workingmen wore shirts that were better made than most people’s shirts are today. Union-made, in the United States. Better fabric, better stitching. There were work shirts that retailed for fifty cents that were closer to today’s Prada than to today’s J.Crew. Fifty cents was an actual amount of money, though. We live in an age of seriously crap mass clothing. They’ve made a science of it.

H: In an essay you wrote for Wired you described much of the appeal of mechanical wind watches is their “Tamagotchi Gesture”, meaning the wearer has to actively keep them alive. Does raw denim and/or repro workwear/military wear have their own Tamagotchi Gestures? Would rituals like washing your jeans in the tub or DIY repairs qualify?

WG: Probably, though it’s a depressing thought.

H: You worked as a vintage picker during the 70s before your writing career took off. What were collectors looking for back then? Where and how did you find the goods?

WG: Not “worked as”, so much as “survived while unemployed in part by doing”. I developed an eye for downscale Art Moderne doohickies, just as that was starting to become a thing. I’d find chrome airplane ashtrays in charity shops. Cigarette boxes. Had there been an Internet, that stuff would have all migrated to Portobello Road by then.

When I started, there were no vintage clothing retailers in Toronto, that I knew of. The big charity stores were awash with amazing vintage clothing, but there was scarcely a market, so I never tried to resell any. Turnbull & Asser detachable-collar shirts, laundered in the 1950s and left in a drawer til the old dude died, one dollar at Crippled Civilians. Good as new.

H: Many of the most sought after vintage items are military pieces from WWII through Vietnam–A-2s, M-65s, MA-1s, Boondocker boots, etc. Will their popularity eventually fade away? Do you think any current pieces of military apparel will have the same lasting appeal?

WG: It will become not the thing, and then it will again belong to the people who totally get it, until it becomes the thing again. I think Caleb Crye’s combat pants, for Crye Precision, will be around after the wars they were built for are forgotten, but it’s too soon to wear them now without being taken for a mall-ninja.

Crye Precision G3 combat pants.

H: Do you still collect vintage clothing or watches? If so, what are some of the prized pieces in your collection? What grails are you still hunting for?

WG: I’ve never actually been a collector. I like the learning-curve, but I buy things, sell them to finance other things. I have fewer than ten watches now, none amazingly rare, though some quite odd. Not a grail kind of guy.

H: In Pattern Recognition, Cayce dresses in clothing items called CPUs, or Cayce Pollard Units, which are “…either black, white, or gray, and ideally seem to have come into this world without human intervention…She is, literally, allergic to fashion. She can only tolerate things that could have been worn, to a general lack of comment, during any year between 1945 and 2000.” Is this an accurate appraisal of your personal style? If not, do you have a set of guidelines like Cayce that govern what you wear?

WG: She’s an exaggerated take on one impulse of mine. I have more technical streetwear than repro-vintage: Acronym (Errolson’s by far my favorite designer), Arcteryx Veilence, Outlier, Finnisterre (cold water surf clothing from Cornwall). The other side is the Self Edge side, where as I’ve said I really like Iron Heart. Stevenson Overall Company jeans. Some Nigel Cabourn. And actually quite a bit of Buzz Rickson William Gibson Collection.

My rule is that if Dick Cheney couldn’t wear it without creating a stir, I shouldn’t either. I like clothing that isn’t easily noticed. I know a man in London who wears Savile Row suits the way some people wear hoodies, and he says the greatest thing about them is that “nobody knows what you’ve got”. They actually have *no* labels. Very Cayce.

Dick Cheney in an N-3 snorkel parka at the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in 2005. It created quite a stir. Image via: Washington Post.

H: I’ve often thought of raw denim as the world’s most subtle gang sign–you could be wearing Iron Hearts and a Rickson’s loopwheeled sweatshirt and 99 out of 100 people couldn’t tell you apart from someone who bought similar items at the mall. That 1 person, however, could spot you from 100 feet away and know exactly what brands you have on and probably how much wear you’ve put into them. Is that part of the appeal for you, that it isn’t easily noticed but it is by the people who care?

WG: Not so much, actually. It’s not about exclusivity, for me, or about *hyper-coded* exclusivity, or any kind of clubbiness. I’m embarrassed if I think anyone knows exactly what I paid for something, or even where I got it. I want what I’m wearing to feel good on, wear well, and to be extremely functional.

There’s an idea called “gray man”, in the security business, that I find interesting. They teach people to dress unobtrusively. Chinos instead of combat pants, and if you really need the extra pockets, a better design conceals them. They assume, actually, that the bad guys will shoot all the guys wearing combat pants first, just to be sure. I don’t have that as a concern, but there’s something appealingly “low-drag” about gray man theory: reduced friction with one’s environment. Arc’teryx Veilance had a lot of that in its original DNA, and I also find it, though probably for different reasons, in Outlier. Nothing worse than clothing that gets in its wearer’s way.

H: How has the internet changed the way we discuss clothing? Every subculture has been balkanized to message boards and niche sites (Heddels, for one) that cater to very specific interests. For many, the way they dress is determined more by where they hang out online instead of where they hang out in real life. Do you think regional styles and cultures will be completely supplanted by their online counterparts?

WG: For one thing, it’s made *visible* the ways in which various sorts of men think about clothing, and made that widely, democratically available to other men. That’s really quite remarkable, new, and something whose implications aren’t entirely clear yet. Men used to do this one-on-one, or in very small groups. But it required a sort of mutual permission, and more trust in other men than many had.

A cultural inability in this area was basically what made men’s magazines of the non-wank variety commercially viable. You couldn’t ask, but Esquire would tell you, on a monthly basis. But it’s easier to genuinely grasp a “look” if you can observe it being worn successfully on the street, which continues to give major urban centers an edge.

Today it’s not uncommon to see men who’ve gone to considerable care and expense to get some very specific look exactly wrong, and I suspect that that’s down to the internet. There are some things that bulletin boards can’t really convey. You have to see it being worn well.

H: How has online retail affected the way we buy clothes? As per the above question, having very specific taste means you have to buy your clothes online. Do you think brick and mortar retail going to fade away except for the die-hard establishments like Self Edge, Blue in Green, etc.?

Also, online shopping often makes me feel like I’m not really buying the physical product (how the fabric feels, fits, how heavy it is), I’m buying the picture of it instead. Are we inadvertently training designers to create clothes that photograph well instead of clothes that look good in real life?

WG: Designing for “rack-appeal” is all too common, and not new, and I don’t see how the web version really differs from that. Most of the clothing I like lacks rack-appeal, because it’s rigorously designed for functionality, comfort, fit, none of which have anything to do with how it looks on a hanger. You can’t get what it does for you by looking at photographs of it. Buying clothing that way is like buying your home off a website, without having been inside it.

Errolson Hugh sometimes speaks of clothing as “micro-architecture”, and I accept that quite literally. We live in our clothes. They’re the architecture closest to us.

H: Thanks for your time!

WG: I’ve enjoyed it. Thank you.

You can find the Buzz Rickson’s William Gibson Collection for sale at Self Edge and learn more about Mr. Gibson on his website. His most recent novel, The Peripheral, is currently available on Amazon.

Lead image courtesy of Penguin Publishing and photographed by Michael O’Shea.