Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

There’s no question–vinyl records are back. You can now find them again at the bookstore, at the mall, at Urban Outfitters. Buying music in a tangible format is now a conscious decision and you can’t get more tangible than a 12” LP record.

They’ve never been gone for me – I grew up with the format and there’s still tons of music out there that’s only ever been released on vinyl. But why invest now that there’s Spotify and mp3s and phones that you can store hundreds of hours of music on? It’s a great question and one that I’d answer by comparing listening to portable digital media to talking your friends via vidchat. It’s convenient and better than nothing, but there’s something unique about occupying the same space with people you connect to, responding to each others’ physical presence and just being together and experiencing the exact same thing at the same time.

Stereos were designed to replicate a concert – or more specifically, to reproduce the sound produced by musicians performing live, on a stage, in front of you. While headphone listening can also be great, it exists in your head – you can kick off a literally endless supply of music by two taps on your phone and that’s it. Compare that to the process of taking an LP, teasing it from its sleeve, placing it on the turntable, flipping a switch to start the platter rotating and placing the needle in the groove – each step an interaction with a physical object, a ritual that’s been repeated by millions of people for decades.

And yes, I’d argue that records sound better if you take the care to do it the right way (although not always better than CDs – more on that later). Not unlike raw denim, the format has its fair share of myths and marketing gimmicks. Vinyl records also require good care to get the best out of them. If you’re just dipping your toes into this analog world or are looking for help on where and how to start, here are some tips to get you on the right path.

To establish some basic terminology, a turntable consists of a platter driven by a motor and a needle that reads the music off of a groove on the record. This needle is housed in a cartridge, which is mounted to a tonearm that is anchored to the base of the turntable. You used to have to plug a turntable into a receiver (the brains of a stereo, with all the buttons and volume knob), through which you’d connect the speakers – but these days you can even skip that piece.

Do No Harm

Vinyl is fragile and can be easily damaged – in both obvious and invisible ways. One of the most insidious ways you can damage a record is during playback – remember, your needle is dragging through the groove of the record. The weight of this needle on the record is called the tracking force. Too heavy a force and it will plow the groove down – too light and it can mistrack and bounce around with the same potential for damage. Either way, you could be ruining your needle and the record at the same time. What’s worse, this kind of damage is often invisible and hard to detect until it’s too late to save either.

All of this can be prevented by keeping your cartridge in good shape and making sure to calibrate your tonearm in line with manufacturer recommendations. Most tonearms can be calibrated for tracking force with a counterweight (a dial-like donut around the opposite end of the tonearm to the cartridge) and a separate setting called anti-skating (usually a different dial at the base of where the tonearm connects to the turntable… your needle is never tracking a straight line – so as it goes in a spiral, it needs something to offset the constant pulling of the needle toward the center of the turntable). Check your manuals for recommended settings and then check out Andrew Chasin’s Beginner’s Guide to Turntable Setup. It’ll be worth it, just like those steps you take to soak your jeans to get ready for serious wear.

Note – if you don’t have a turntable, or your existing turntable doesn’t have these settings (this a concern many have raised with the Crosley portable setups that have gained in popularity of late), I seriously recommend upgrading to one that does. Music Hall makes a well-received turntable (USB-1, about $250) that can plug directly into your computer, a stereo receiver or powered speakers (if you don’t have a receiver, powered speakers are a good way to get started – Audioengine A5+’s have been getting good reviews and are currently available for about $400 a pair, so you can get a decent sounding setup from scratch for less than $700) .

If your turntable does have these settings, but you’re not sure when they were last set or checked, you may want to cut your potential losses and start fresh with a new cartridge.

What To Buy: (aka – vinyl always sounds better than digital, right?)

In my experience, this is a trick question along the lines of whether or not selvedge denim is “better” than non-selvedge denim. Just like with denim, what matters most is what goes into producing the item. The biggest determining factor between any two versions of the same recording (regardless of, and despite, format) is in their relative mastering.

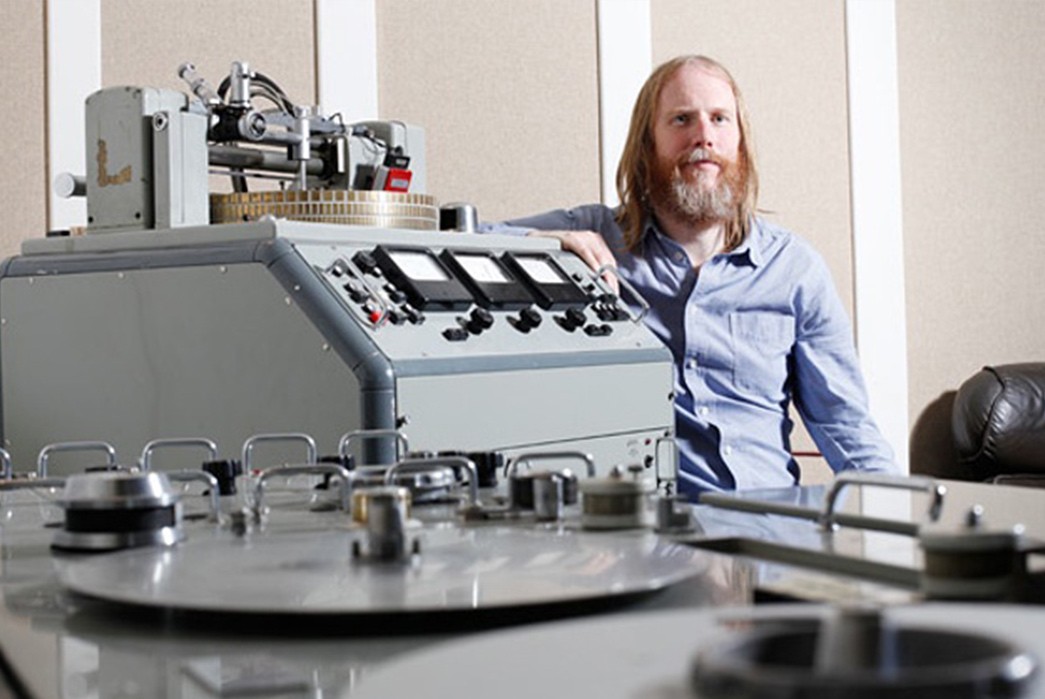

Mastering is the process of taking a recorded mix (the result of a recording session, say) and processing it into something that will be used to create the final product (the master) – in the case of vinyl, it’s usually provided as a service by the place that actually creates the physical records (the pressing plant). The crazy part is that it’s all done on the fly – the mastering engineer will play the mix through electrical equipment that can be tweaked to minimize audio defects, while a machine called a cutting lathe makes a record-like acetate that will be used to create the mold for vinyl down the line. I am simplifying the process greatly, but suffice to say: when going from digital sources to vinyl (or even analog tape to a CD), it’s a heck of a lot more complicated than pressing a “record” button – skill and experience matter. Because of this, the mastering engineer is critical to a great sounding record.

Why do I mention this? It’s because an insensitive (or downright lousy) mastering job can make a record sound lousy – no matter how great the recording medium. In the eighties, when CDs were introduced, record labels fell all over themselves trying to get as much of their back catalog available in the new, lucrative, format. In the process, they released tons of terrible sounding CDs onto the market – there weren’t enough skilled mastering engineers out there to keep up with the demand.

Similar things are happening now and have been going on for at least the last ten years – I’ve had experience with lazily mastered LPs produced under such marketing as heavyweight “180 gram” vinyl to try and mask their flaws. Before you buy a vinyl reissue, check to see if it credits the mastering engineer (“mastered by”), where it was cut, or even where it was mastered (none of this counts if the artwork is a vintage reproduction). It’s not necessarily bad if it doesn’t say anything, but it may not be that special either.

Fig. 5 – Pete Hutchison of Electric Recording Co. in his studio in London. Yes, this photo was taken recently. Image via The Guardian.

As an example of a label going to extremes to get these details right, The Electric Recording Co. was launched in 2011 with the goal of creating faithfully reproduced vintage classical music recordings from the fifties and sixties (which command insane premiums for good condition copies due to scarcity and the desirability of certain performances). To do so, they use restored, period correct equipment from that era (in a real-life fulfillment of the myth of Japanese denim makers buying up old Levi’s looms). The end product is breathtaking. It’s not something I’d recommend for everyone, but I absolutely respect the label’s commitment and vision.

What to Buy: Another word about reissues (and CDs)

The great thing about vinyl reissues is that they are completely pristine – you don’t have to worry about someone else having wrecked them with a damaged cartridge! But they carry with them the possibility of dubious provenance or production.

My rule of thumb is: recordings mostly sound best in their original release. Before the mid to late 80s, that was vinyl (and when looking at expensive new run of the mill vinyl reissues, do consider if there are more affordable secondhand pre-90s vinyl of the same records). After the late 80s, digital (DAT) tapes became standard in the recording studio and CDs became more prevalent – this is significant because it’s easier to make a digital master from a digital source than making analog from digital (or vice versa).

Right now, there’s a huge fad for vintage 90s indie vinyl, but I’ve yet to hear many examples of that vinyl sounding better than the CD. There’s still joy to be had in having vintage indie rock on vinyl (there was practically a political movement within the community around keeping vinyl alive, after all) but it’s worth thinking about when debating spending your hard earned cash on a $50 LP when could buy the CD for $5. And if these CDs don’t sound good, maybe you need a better CD player?

Where to Buy

Fig. 6 – The WFMU Record Fair in 2009. Image via Jazz Collector.

My number one recommendation is – if there’s a decent record fair near you, it is absolutely the best option. The people who run the stalls are often fans themselves who want to share music with other fans (even though they may not always seem that way). Also, record fairs are time bound so you can often negotiate great deals close to closing time. The WFMU record fair in New York City and Austin Record Convention are probably the two best in the US right now, but there’s regional ones worth checking out (including KUSF in San Francisco, Night Owl in Portland and the tri-state area’s Record Riots). [Full disclosure – I sell parts of my personal collection at WFMU (and used to be a volunteer DJ there). I also sell at some of the CT Record Riots.]

Record stores have had a tough time and the best ones are surviving due to a combination of good records (at a decent price), a steady replenishment of pre-owned inventory and acceptable customer service (at minimum, record store employees should be able to help you find what you want – but the best ones can also recommend new things based on what you like without making you feel like their staff would rather be doing something else). Amoeba is dominating the west coast now, in Chicago you have Reckless Records and in NYC, Academy is probably the best all around record store (though Other Music offers a more edited experience).

Other than that, there’s online – there’s tons of options out there for online retail (I still love Forced Exposure for its sheer selection across all genres – even / especially genres you didn’t know existed). The ubiquitous eBay is better for more coveted items and Discogs is a great site that allows you to both track your collection and look for particular releases.

A Quick Note on Condition

For a fragile format, condition matters. The number one thing to look for is called lustre – is the surface of the record shiny or is it matte / non-reflective? Matte is not necessarily a bad thing, but lustre is a good positive indicator. Also, be on the lookout for scratches you can feel with your finger (run it across the scratch gently) – those are not good, but don’t be prejudiced by light surface marks and scuffs. Dealers and stores often evaluate (grade) condition visually and I’ve found many great deals by identifying surface marks that decrease the grade but don’t affect playback. This will come with experience, so don’t be discouraged if you misjudge one every now and again.

Finally

Always remember: it’s about the music, right? So don’t feel pressured by an audiophile opinion that has no relevance to your listening habits. And make sure you can sit back and enjoy it every once in a while. I listen to my iPod often, but it’s a special treat to sit in front of my stereo and listen to an old favorite or something new with complete focus and open ears. An experience in a place, at a time.