We had the chance for a lengthy chat with Donwan Harrell, the founder and creative lead at PRPS, one of the biggest premium denim labels in the world.

Yesterday’s installment covered the beginnings of the PRPS brand and Donwan’s first exposure to Japanese denim. Today we dive deeper into his passion for vintage workwear, the shifting relationship between American and Japanese culture, and what he sees for the the future of denim.

David Shuck (Heddels): You had this collaboration with Lee that’s sitting on a rack right behind me here.

Donwan Harrell: Yes. That was an enormous opportunity for me even to be considered and be approached by these guys. But it was probably one of the best opportunities I’ve ever been given outside of just my partners allowing me to be able to do the type of job that I do. I mean we all know these guys created the idea of putting zippers in a jean. And so there’s a lot of heritage and history that comes with working with a company like that.

And when the assignment was given to me, that I was going to be one of the people to represent them for their hundred and twenty-fifth anniversary, I learned I had complete carte blanche. I could do whatever I wanted to do, research whatever I wanted to do, and then kind of present to them back in Europe the concept at VF, because VF holds the label in Europe. And so I went back, I was so excited, and you have a ton of ideas going through your mind. I was like oh I should do the 101B, I should do the 101J? I’m gonna start one of my own personal vintage collection and use that as my vehicle to present back to them, because it’d be great to kinda like do the collection, pick out the fabrications in Japan, put it together in Japan, and then take with me the vintage pieces that I was inspired by so it creates a story.

And it’s kinda like what I was speaking to you the other day, showing you the overalls and how I was able to modify it to make it, you know, commercially sellable but not make it too destroyed. But at the same time get the character and the look of Lee without screwing up the heritage look of the company. So I wanted to stick with the exact silhouettes, but just modify them just a little bit just so they had a modern touch and feel, but do not touch the actual CMT or the character that they’ve already implemented within the style.

I created a slew of raw because I know in Europe there’s definitely a strong presence of guys who like raw denim. Then I was going to do the vintage replications of those as well. And that’s what I presented back to Lee, and they just loved it. And I did my specialty which is vintage replication and washing. I did my spin on that, and they just loved the character of each wash.

H: You forget here in the United States what Lee was and what Lee is capable of because they haven’t done all that much to sort of approach the American market with that higher end heritage level. You forget that it’s the jeans that James Dean wore. It’s the jeans that Steve McQueen wore.

DH: Robert DeNiro, I mean so many of these guys.

H: Yeah, and they’re starting to get on top of that with their Lee 101 line, but nothing like this. Nothing like what Lee Europe is making.

DH: A lot of Americans may not know this, but there’s a company back in the day called Chevingon. This is like way back. And it was my first time seeing it in the US. And it wasn’t an American company, it was a European company. And this is before Diesel and before Big Star or any of those types of companies. The Europeans have been involved in American Heritage for a very, very long time. And even Diesel and Replay being inspired by American Denim and having these really cool collections.

But so I think in general it was easier for a European company to come to a US designer and as a US designer to design something for them that would work for them. Knowing that I have been in the Japanese denim business and a heritage business for a very long time. And I just think that was a natural marriage and it worked out well, very well.

H: Do you see in the future that a lot of these American Heritage brands will be bringing that upmarket heritage side of their company back to the States? Because it seems like so many of these old companies are producing these amazing things for Europe and the Japanese market but the States get left behind.

DH: I’m hoping for the best, but a lot of times the bean counters take control. And the bean counters have to have their sales at Sears and JC Penney and all these types of companies, and it’s always about the end dollar, but I think we as a people consistently have to constantly push the envelope and want to buy the better. Because that’s what the company was about beforehand. It wasn’t always about the commodity end of the business. But I’m hoping that these companies will continue to push and evolve their product and allow for a great designer to showcase what they can do for different companies like what Lee has asked me to do. I just cross my fingers and hope for the best.

H: About five years ago when I was in Japan I remember I was in the Tokyu Hands store, and I saw all these amazing backpacks from Gregory, the American mountaineering company. And they look just like the ones you’d seen in the late 70s, early 80s with the suede zipper pull-tabs and the contrast ripstop fabric, and there was one that I saw, and it was twenty thousand, thirty thousand yen. And I thought, “Oh I’ll get that back home; it’s probably cheaper.” And I went back, and…

DH: They don’t have it, they don’t have it at all.

H: I emailed the people at Gregory. I was like oh I found this backpack I really liked, can I get it here in the States? And they say, “No we don’t offer that here in the States, it’s made domestically but it only goes to Japan.”

DH: Exactly.

H: So the only made in America stuff for that company was sold abroad, and only the stuff produced abroad was sold in America.

DH: I believe it. You know I’m a gigantic fan of the company Russell Moccasin. I have a pretty extensive collection that I’ve been buying, but I can only find the models I want in Japan. You know, because if you try to find it here it’s a very small cylinder sole, but you have to go to Japan to find all the different models that they have the capability of making. And so it’s just sad that I can’t just go to the local store here in the city and buy like these cool Russell Moccasins, but I have to go all the way to Harajuku to buy it. You know?

H: It’s just, that’s where it’s appreciated, so that’s where it is.

DH: Exactly, exactly. You know? But that’s just the way it is.

H: Where do you think that American denim is at the moment from its influence from the Japanese denim market? It seems like we’re sort of living the reflection now of what Japan thought we were.

DH: Yes, we are. And I definitely agree, so I think we’ve come a long way. It’s kinda like what I was saying before with a lot of the bigger chain stores offering Japanese selvedge in the mall. We’re in a position where a great many people in the East coast and the West coast are starting to acknowledge and comprehend what premium denim is. I don’t know too much about Middle America, but I definitely know on the East and West coast there is a huge appreciation of Japanese denim and high-end American denim like Cone Mills taking, you know, real estate up in some of the better stores. And I think that’s inevitably going to influence and start to kind of sink more into America from the East and West into the middle. I think it’s inevitable.

H: Yeah, well I think it’s going there right now. Like you see stores like this opening up in Denver, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Austin, Portland, St. Louis, Minneapolis, it’s getting there.

DH: And you see it on the blogs, you see it on comments from people all over America really starting to learn and comprehend what premium denim is, and you can see they’re actually doing research, and they’ll know about this tiny company here making denim and they know about this tiny company here making denim, and it’s all really great old-school craftsmanship and Union Specials, and getting this fabric from here, or this is dead stock fabric from this mill here. And you see like there’s this community, this incubator community of denim purists starting to bubble up in the US. And that’s just going to inevitably just influence more and more people as time goes on. And it’s just nice to be a part of something from the beginning and see how it’s flourished over time.

H: Just this idea of premium denim has always been something that’s interesting to me because, as you would know probably better than anyone, with all the old garments surrounding us here that denim and workwear were primarily made for hardscrabble blue-collar workers that were down in the mines, and now those same designs and the same fabrications are now being sold at places like Bergdorf’s and Barney’s. And it’s an ultra-high market. Do you feel like there’s some philosophical disconnect between those two, like what denim was and what denim is now and how those same designs mean different things to just polar opposite classes of people?

DH: Yes that’s correct, but you know a great example is like the Comme des Garçon jackets. You know he was doing all those original work wear chores style jackets, but he was doing them in like mixed denim with leather piecing, and there’s something to appreciate the artistic aspect of that. Maybe as a designer I look at it and I look at as artistic, but maybe the average customer seeing it does not know that it was inspired by an original tour jacket or a Lee jacket or a Pointer jacket of some sort or nature. Because, obviously, I don’t know exactly what vintage piece he took it from.

But for me, I love it because he’s pushing the envelope with vintage inspiration, and whereas the average consumer that may be able to actually to afford that jacket, he probably doesn’t know that it’s inspired by vintage. But I think all of it, we have to come at it at different angles to educate the consumer. Whether they are familiar with it or not, I think we all have that responsibility to educate the consumer because we are the originators of all of that in America. And it’s important that we kind of re-educate them and kind of communicate that, you know, all these types of details that we see and some of these heritage brands were early farm or mechanic or engineer or you know what have you, influences in the product. Whether it’s the watch pocket or whether it’s the Wabash fabrication or the two by one fabrication, whatever that’s in the uniform, I think that’s important that we try to utilize these fabrications because these are things that we created here into our modern day collections which I do today.

Still from a 2012 PRPS lookbook shot by Eric Kvatek.

H: It’s something that I’ve always struggled with, and what keeps me coming back to denim and why I find it so endlessly fascinating is just the cultural forces at play, like why this is valuable to us and like what the value we see in these garments in this day and age.

DH: Because you know what, we live in a world where you know it’s all about fast food. And it’s all about now. And you know I like the idea of pushing the mills to do better and better fabrication and bring them back an old garment that has a weave that has not been out for awhile or has not been out in years. And, you know, because what happens is we want faster shuttles to make denim, we want wider, you know, width to make denim so that we can get more pattern pieces. No, I like the old way of making things. There was nothing wrong with it, you know? Even if that’s for a select group of people that appreciate it, let’s go back, let’s try to do these types of things, you know? I think that’s important because if you have an appreciation for something that’s a reason why.

It’s just like I always go back to car companies. There’s a reason why BMW will come out with a specialty car or Lamborghini with a specialty car, is because there’s a guy who actually wants something like that. Who understands and wants them to push the envelope. But I think us as consumers, if I have a PRPS fan he wants me to create that one jean that’s, you know, that takes X amount of days to dye or you know takes X amount of machines to make.

H: They want to superlative.

DH: Yes, exactly.

H: They want the best, most labor-intensive, most like insane jean you can think of.

DH: And they don’t care how much it costs.

H: That has moon rocks scraped against it to make the fades.

DH: Exactly, exactly. Has to be hand-dyed and soaked for three days or whatever the case may be.

H: I also think it’s sort of fascinating that if you look at say the percentage of what an annual American household would spend on clothing like a hundred years ago, it’s something like ten, fifteen percent I’m not sure the exact number on that. But you go to today and it’s like, you know, four, five percent. And the people back then they had maybe like two, three changes of clothing unless they were exceptionally wealthy, so you had to have clothing like this that was made much better that would last longer.

Still from a 2012 PRPS lookbook shot by Eric Kvatek.

DH: Yes, you’re absolutely correct.

H: That would sort of stand up to the abuse of being worn every day for years which is, I guess, the way we’re taking it up now.

DH: That’s true, that’s true. They didn’t have the dry cleaner up the street like we do up the block from our apartment, so…

H: And they didn’t have an H&M that they could just buy a new shirt for five dollars if they wanted to.

DH: Exactly, exactly so typically the wife or whoever the housekeeper was at the time would always mend the garments so that they could continue to wear because they’re not gonna go buy a jean once every couple of months. They will buy a jean once every couple of years. You know, and that was just the market back then.

And jeans, back then we don’t really think about it as you know average the Americans today, but the jeans sat right next to the shoveling tools and the cans of beans and it was dry goods. You know, it was a dry goods store. And so the dry goods chambray shirt that was raw would sit right next to the dry you know salvage jean that was folded up right next to the can of beans. You know, and it’s like that was how they lived and survived.

H: Yeah, one of the favorite things that I saw at Brit Eaton’s place in Durango was this pair of Wabash jeans that had like you know pinstripes up the pants that he had found. He said, “Oh it’s for the guy who works in the mines and then wants to go have dinner at the saloon or something, and he doesn’t have a suit he can put on, so his jeans have pinstripes on them so he can fake it.”

DH: Yeah, exactly right. You know Brit’s a phenomenal historian when it comes to that stuff, and you’re right because there was no multiple changing of clothing for these guys back then, you know, a lot of times these guys wouldn’t take a bath except maybe once a week. If that.

H: They weren’t putting lotion on afterwards either.

DH: Exactly. Definitely no lotion. But yeah so you know Brit’s a phenomenal, incredible vintage historian and collector and he’s been a huge resource for me historically in providing me knowledge and vintage to spawn off all the incredible denim washes that I’ve had in my company for years.

H: And how long have you been collecting vintage?

DH: Oh my god, since the mid-90s.

H: Because just like a cursory glance we’re sitting around like two hundred thousand dollars worth of denim here.

DH: If not more. And that’s only in this office.

H: Yeah that’s only in this room here.

DH: But I’ve been collecting, I’m fascinated by vintage for many, many years, and you know the average person may not know how much vintage is influenced within my product, from every nick, every tear, every abrasion, every grind. There is a vintage that I’m mimicking, so there’s history in each item that I’m selling to the general public, and I’m hoping that they appreciate that. That I’m trying to be as real and as authentic in my PRPS Noir and Japan line as much as possible.

H: What are some of the favorite pieces you’ve come across in your years of collecting?

DH: Me personally, I love collecting jeans. But there are two things I love collecting the most, and that’s military, rare military items, and coveralls. Coveralls and overalls. I find that more, you find it’s easier to find a beautiful overall with character than it is to find a denim jean with character. And it’s because more Americans back then working on the farms or in the fields or what have you wore overalls. There’s so many beat up overalls still left in America, in a barn, under a car, or somewhere in the backyards. I tend to prefer to collect those and I have a great many of them over the years.

H: Are there any ones with like crazy fades in them or a crazy story behind them?

DH: Oh my God, yes I have some amazing ones. I have ones that were used as insulation in a house where it has incredible sun fade because it’s been left between the walls–again this is before insulation in buildings. And so if something’s been worn out and they want to buy a new one, these items became multi-purpose. Whether it was being used to wash down something they’d cut it up and wash down, or cut up to repair holes for a new one or use as insulation into a building, and the sun would beat it, and you know we would find it inside of an old building that has been completely unused over years, pull it out of the building, and you had this incredible patina from the sun over the years and inside the rivets. After you get the bird’s nest off of it and what have you. But it’s just amazing, that’s what I enjoy looking at.

Still from a 2012 PRPS lookbook shot by Eric Kvatek.

H: There was one that Brit showed me that was there that he had pulled out of the ground because someone had used like old pairs of 501s to plug up gopher holes in the back of his property.

DH: Multi-use, that’s what I said, denim was multi-use back then. It doesn’t matter, that’s what we love about them. And that’s the thing that gives it character, you know? That’s the thing that gives it character, the high and low effect from being used in that manner is what I use to get inspired to do the denim. And because the indigo is such dark, it’s so dark, depending on the dips of indigo that the manufacturer used, there’s so much character that is developed from how it’s folded and left when the sun beats on it or how the water gets on it or how the dirt grinds off of it to give it that really cool crossfire effect from fading. But that’s what I’m inspired by and that’s what I love to see when I find one.

H: Do you have anything that you’ve been searching for for like the last twenty years that you just, it’s the one grail that you never got?

DH: We are always, I think most denim collectors are always looking for the single back pocket buckle back. I think that’s the number one jean because that right there is worth so much money. But the single back pocket buckle back is, we tend to always…

H: That’s the grail. Do you have any in your collection now?

DH: I wish I did. I have buckle backs with double pockets, but no single pockets. That right there dictates the age.

H: That’s 1890s or earlier.

DH: That is correct, yes, 1800s. Those are really difficult to come by, those are really rare, and I think only a couple of people actually have those in hand. I am pretty sure there is some barn or a shack in a woods somewhere that still has a pair.

H: Some mythological place out there that just exists in every denim-hunter’s mind or vintage collector’s that oh, this is the barn, this is the cabin that no one’s found for a hundred years that has the perfect jean.

DH: It’s inevitable, there’s always stuff out there. Because you know America’s really big, and there are people all over, and you know it’s inevitable that it’s somewhere.

H: At the same time, vintage, it’s a finite resource. You know it’s like you’re mining gold out of the ground. You can only mine those miners for so long.

Inside Brit Eaton’s vintage warehouse in Durango, Colorado.

DH: That’s true, that’s very true. You know, but I keep hopeful and one day I hope to find it and frame it and put it up in my house, you know?

H: What connection do you feel to these vintage garments? Like what attracts you to all these pieces are not only just old denim but also old cars, magazines, posters, just this old sort of pieces of Americana.

DH: I love anything early American because I really felt that you know anything made in early America I feel is extremely well made, and better than what we do today. There was a natural commitment that we had as Americans back then, and I can’t say for myself today, but back then that the Americans felt, and took pride in what they did. You know, whether it is early [American] flags and the construction of the early flags, or early denim, or early cars from the late 60s to early 70s, there was just a certain pride and craftsmanship that’s in these vehicles that have gone and lost.

I’ve been collecting denim and vintage cars for quite a long time, and even in just, you know to switch the topic up with the vintage cars so to speak: I have from 1962 to 1972 many old cars. And just the craftsmanship and the simplicity of those vehicles in the same way that the jeans are is just, that’s what I love about America. Is they had it down to a fine art science, and it was something that was only to be had in America. Like the period in which they were making beautiful jeans before, you know, World War 2 to making muscle cars between, you know, 65 to 71, those times will never be replicated. It’ll never be the same, you know. Those movements where every kid growing up wanted to put big tires and mufflers, new headers on his car and just kinda jack it up and race at night, those times have come and gone.

And you know we want, you know as collectors, Americana collectors, we always want to buy those things, procure those things, because it’s kinda like capturing time. Just like buying these or procuring these overalls and jeans, early jeans, it’s like trying to, you know, capture a period of time that you didn’t exist and kinda holding it close to your heart and appreciating, and hope that somebody else has the same sort of appreciation when they get around it.

H: Do you see that same sort of pride in craftsmanship living on in Japanese like appreciations of denim and the way that they’re building stuff now?

DH: Yes, definitely the same sort of appreciation. And I think that’s the reason why they’ve kinda like held onto it, and tried to replicate it.

H: They’ve taken up the torch.

DH: Yes. And we have kinda gone overseas to try to procure it and make us for our product, many of us denim suppliers, because they do take pride in it. They do. And I wish there was more denim companies, denim mills in the US to kinda come about and do the same thing like Cone Mills is doing. But it’s very expensive, and sometimes there’s just not enough stores willing to buy into that concept, and so we kinda have to work with the few stores that do exist that don’t mind buying that story and that appreciate it.

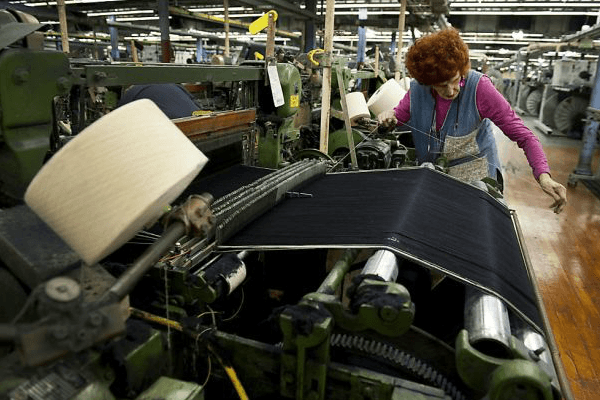

Inside Cone Mills White Oak plant in North Carolina.

H: Do you see that craftsmanship and that pride coming back to the United States manufacturing?

DH: Slowly but surely yes. There’s definitely a sense of bringing manufacturing back to the US. I wish that I could partake in that. I’m hoping so, I mean I’ve been having conversations with one or two companies or manufacturers. I tried once before in California at a line called Heirloom, and it was again completely manufactured in LA. And what I find though is you have to live in LA to manufacture in LA, because what happens is if you’re living in New York and your manufacturer is in LA, unlike the way it is in Asia, there wasn’t a sense of urgency. And so I was late on delivery, and so I couldn’t continue that. I had stores, when stores wanted to buy something they want it in a certain period of time, they want it delivered. So I had to desist, but I want to start it up again, but this time on the east coast. I want something on the east coast, yes.

H: Are there still production companies making jeans out here?

DH: Yes, yes definitely. There’s definitely quite a few that are and I’m in contact with them currently.

H: Probably just you know within a few blocks of where we are right now, honestly.

DH: There’s quite a few companies here manufacturing within a few blocks here that are really good, but I don’t necessarily want it to be made in New York, I want it to be outside of New York just because what happens is the jean stays really expensive, you know. I want something outside of New York to just be, again, to be accessible to the consumer.

H: Where do you see I guess American denim moving now that we’ve had this sort of renaissance about ten years ago and like all these companies that came up, you know like your Imogene + Willie, your Raleigh Denim, your Tellason, do you see those, that movement continuing and then getting stronger?

DH: Yes, that’s not going anywhere and it’s going to grow. And I hope all these companies continue to have the success that we’ve been seeing, and I think more and more stores, you’re gonna see more and more boutique stores carrying these types of product because it gives us a place to go and buy really cool clothes. And it’s given us the ability to have more depth within our range of product. And not just jeans: jean jackets, and I’ve seen denim ties and denim hats and just, it gives us the ability to just create more avenues of selling. And I just see it continuing to grow.

And finishing different product finishing and different methods of washing, it’s just, it’s, there’s just, it’s endless the amounts of capabilities that we’re able to do as long as we keep pushing the product.

H: Sort of to switch subjects here a little bit, but you seem to have a real eye for I guess imagery in the way you’re incorporating early Americana images as well as new Japanese images into your product. And I wanted to ask you about the origin of your logo, the cherub in a sling and on crutches and bruised never broken, what, where that came about.

DH: That’s a long story, but to make it short there is, in 1969 there was this car called the Daytona, and this is a car that went, it was one of the first cars out of production to go two hundred miles an hour. And they used to win every NASCAR event when participating in it, to the point where they were using a 426 Hemi and they were just burning the tires off and beating the competition. To the point where NASCAR said these cars can’t participate anymore, they’re too fast. We’re gonna downsize the engine, these cars are not allowed to race.

Dodge 1969 Daytona Charger. Image via J Mooney Ham.

And I’ve always wanted one, and from that, I was able to buy one quite a number of years ago, and I decided that I was going to have that car represent what jeans was to me. Something that was built for something incredible that the older it gets, the better it gets.

So I didn’t think that putting a car with a wing on it and the nose cone on a jean was going to look right, so I was going to recreate that to be, because back then we used to call them the bird cars, and because it was so fast, it had the wee cool wings on and they had gone through the whole wind tunnel test. These were like the first cars with wings on it by the way, and now most cars have wings on it to some extent, a tiny one in the back. And that’s where the cherub came from. It was my way of reinterpreting the vehicle, sort of it’s…

H: Sort of its personification.

DH: Yeah, and so I had that illustrated up, and that’s what I use as the icon for the company. But it also represents, the bruised never broken, even though it’s been around, it’s been very used, it still serves a purpose just like jeans do. Even though a jean’s been worn out and dusted and abused, just like the car did, it’s not something you just put away and forget. It’s something that still means a lot; that has your character on it, that has memories on it. And that’s what the cherub represents. Even though its beat up and broken, but it’s still you.

H: Yeah, it’s still there, still going.

DH: Still there, yeah.

H: And the name PRPS, where does…

DH: Purpose, purpose. As short for purpose, PRPS. Because denim has lots of purposes. You know, it’s very resilient as I said, it’s a multi-purpose application, so that’s why I came up with purpose, PRPS.

H: Just like your grails with finding vintage goods, what’s your grail collaboration? Who would you want to work with if you had any pick?

DH: You know who I think would be amazing to do a collaboration with that I think would be cool? Is The Gap. I think The Gap would be a really awesome collaboration. There’s a lot you could do with that, you know.

H: Definitely. They’ve done quite a few, like you know very liberal collaborations where they’ve let designers sort of have a lot of free reign like they did on Mark McNairy and Baldwin as well.

DH: But they need a really hardcore denim line that’s in there that could be a really cool collaboration. I think that would be awesome.

H: Something that’s under a hundred dollars in there could really shake things up.

DH: Yes, you know, because they have a core iconic campaign many years ago which was the chino in the big white shirt with the denim jacket. But there’s a way that you could make that really cool vintage, and had that same look, and that I think I could work with.

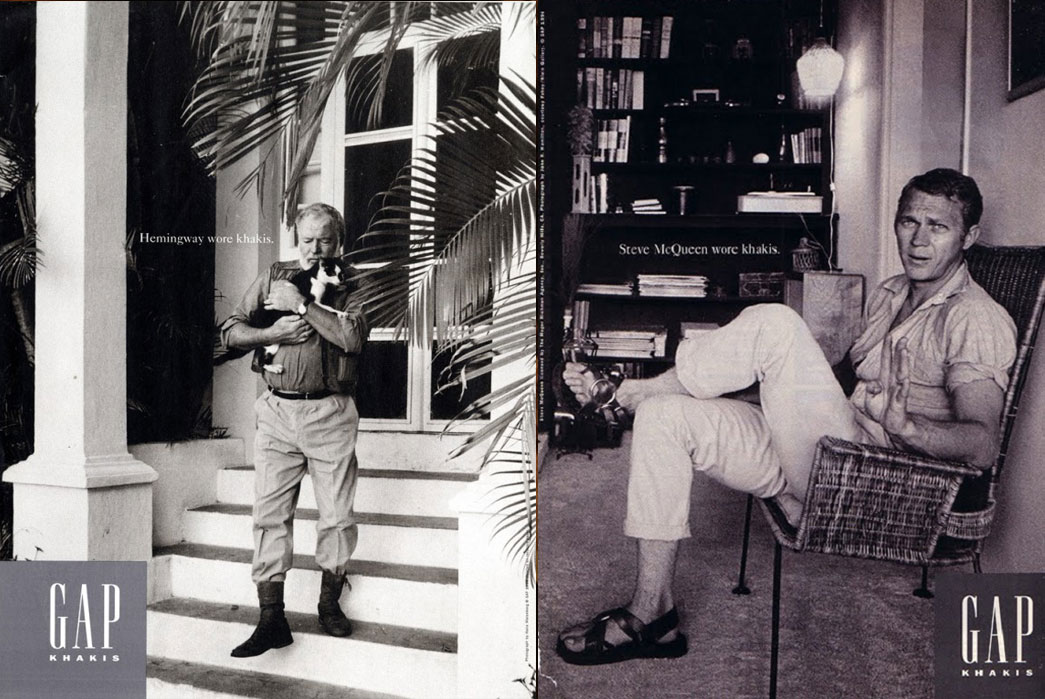

H: They had that whole advertising campaign that was just like images of people wearing khakis and like James Dean wore khakis, Sydney Poitier wore khakis.

DH: Exactly, but imagine that used.

H: Yeah.

DH: That’s one of my dream concepts but I’ll just keep dreaming.

H: Well it’s been a real pleasure Donwan, thank you for taking the time.

DH: No problem, it was a pleasure having you here, and I enjoyed it, and you’re always welcome.

To learn more about PRPS, visit their website.