“Why could the Soviets not replicate Levi 501s the way they had replicated the atomic bomb?” – Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest

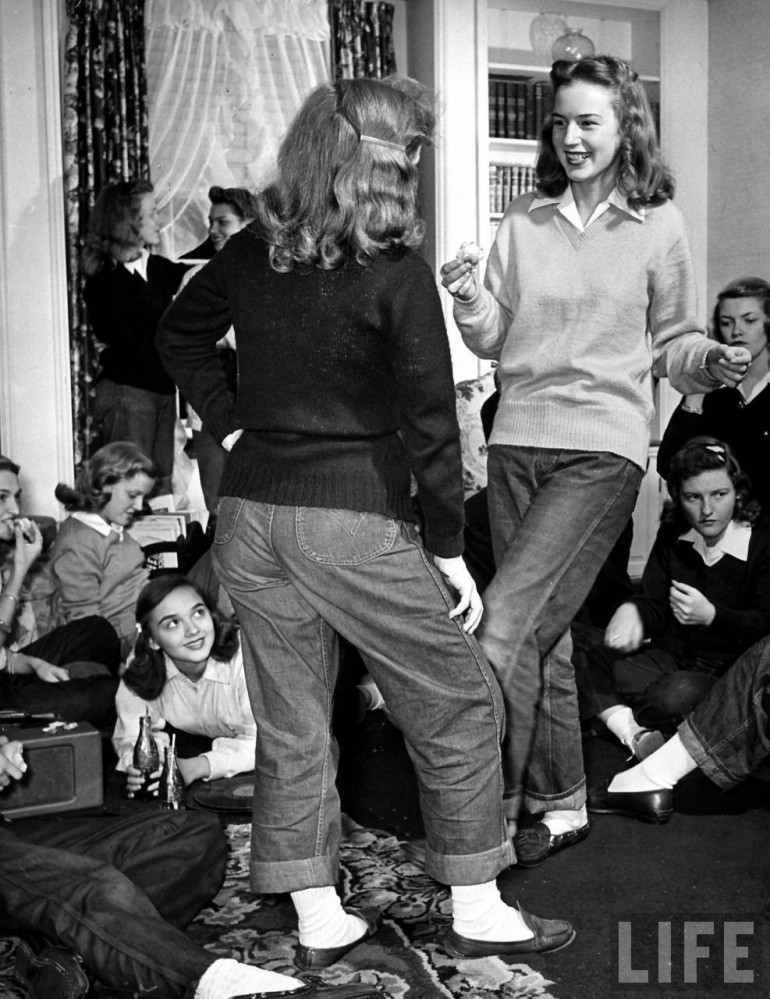

There is “more power in blue jeans and rock and roll than the entire Red Army” said French philosopher Régis Debray, and he wasn’t just speaking symbolically. American denim had incredible economic and aesthetic power beyond the Iron Curtain in the Cold War era, where jeans were an inadvertent piece of the American propaganda apparatus. Young Soviets, rather than emulating the traditional dress and haircuts of their parents, wanted to look like the film icons and rock stars of the West – and they were willing to pay through the teeth to do so.

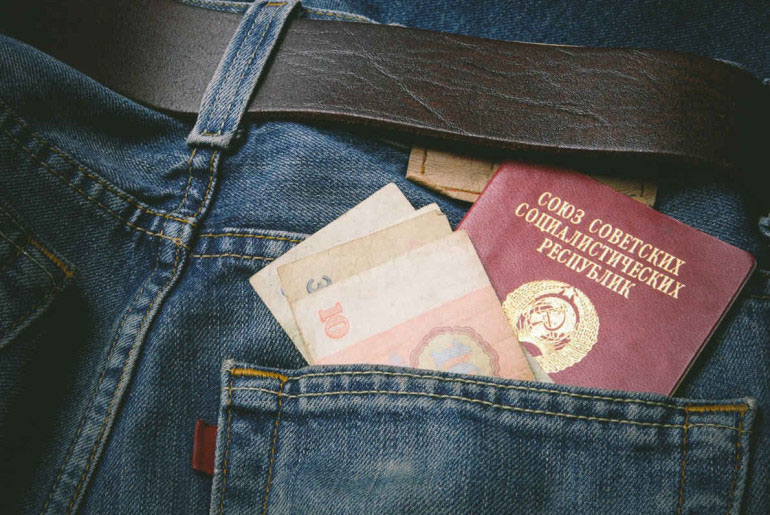

The problem was, denim wasn’t easy to come by. Though never outright banned, there were no direct channels to buy Western goods in the Soviet Union, and the resulting captive market created a lucrative bootleg exchange. The most coveted items were blue jeans, corduroys and leather jackets brought in by diplomats, tourists, sailors and military advisors and resold at high arbitrage prices.

Lingo developed around denim and black market Western commodities. Even the word dzhins itself was a direct cognate of “jeans.” The Czechs called them Texas skis, or “Texan Trousers.” Those who bought and resold foreign goods were fartsovschiki, and the barter of choice was fur hats and caviar for brand-name denim. Law enforcement officials used the unofficial term “jeans crimes” for violations related to the acquisition of denim.

The phrase, which now sounds about as serious as “fashion police,” described very real offenses. One 1978 article in the Georgian newspaper Zarya Vostoka describes five Young Communists jumping a passerby and stabbing him for his jeans. As early as 1963, a pair of girls robbed two other girls with a knife and two straight razors, slashing the face of one of them.

Other, less violent methods for obtaining denim proliferated, as well. A 1972 Life Magazine article claimed that American students “have been known to finance their entire summer European travels by selling off extra Levi’s,” and indeed, Western tourists were approached and offered exorbitant sums by young Soviets looking to buy the jeans right off their body. Jeans went for around two hundred rubles, or a month’s salary for the average worker. An ordinary pair of state trousers went for ten to twenty.

So why not make high-quality Soviet denim to compete with the American brands? For one, making jeans would be a response to consumer demand, rather than Party supply, and was thus an insupportably Capitalist undertaking. And where Westerners saw a simple problem – the desire for jeans could be easily satisfied with the product itself – Soviets saw a symptom of a much deeper decay of values. It was a question of principle, not technology. As a 1981 Lodi News Sentinel article put it: “All these ‘prestige’ goods have nothing to do with ethics or morals.”

The simple fact that young people were so obsessed with any product contradicted Party ideology. Members of the older generation lamented the substitution of material goods for spiritual ones. Jeans culture was a type of philistinism, and slogans like “prosperity without culture” and “predatory consumerism” entered into anti-jeans rhetoric. Parents were chastised for indulging their children, and encouraged to talk to them about fashion in the context of their intellectual, moral, and social potential.

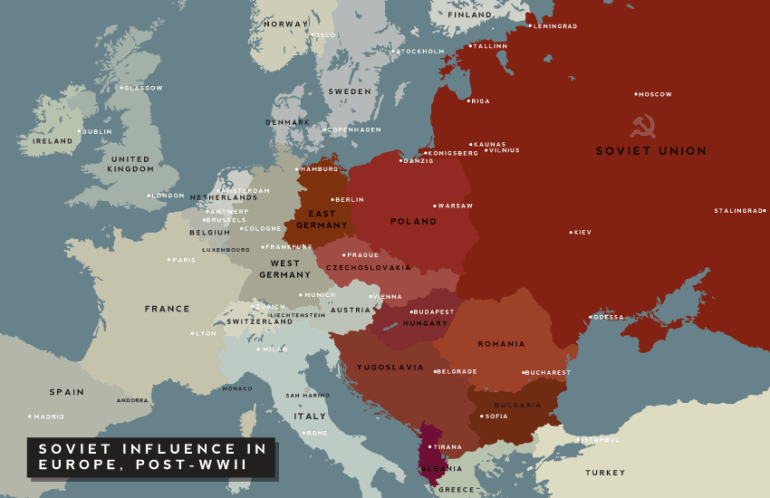

Then, there was the nature of denim itself, known in East Germany as an “embodiment of Anglo-Saxon cultural imperialism.” A 1979 Guardian article went as far as to say “official Soviet doctrine has held that Western jeans, being figure-hugging, are a symbol of Western decadence, and thus to be avoided in the same way as pornography,” echoing the shock the United States had once felt when a 1944 Life Magazine photograph showed Wellesley women in denim trousers.

But after philosophy repeatedly failed to turn the denim tides, Soviet leadership relented. First, they tried to produce and popularize their own jeans; in 1975, the Ministry of Light Industry began to manufacture Soviet denim, to limited success. The quality did not match those of American-made jeans. As late as 1984, a reader wrote in to the Soviet Communist Party daily Pravda: “When you can make jeans better than Levi’s, that will be the time to start talking about national pride.”

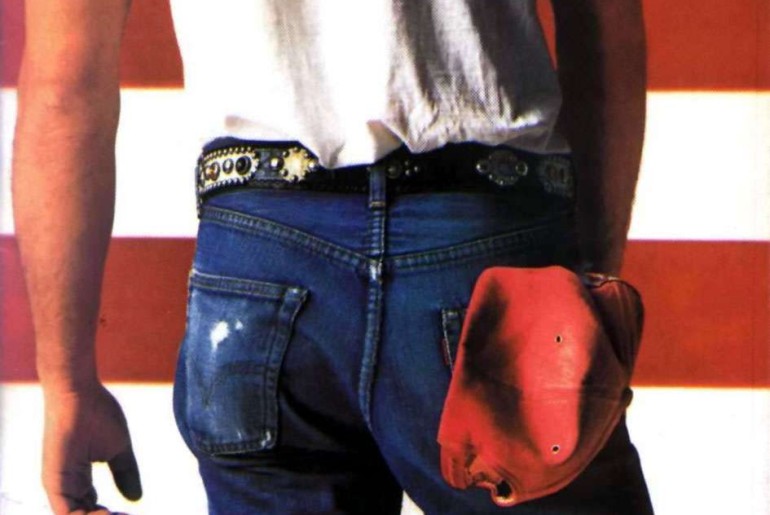

Further, the cache of jeans themselves was in association to the Westerners who made jeans glamorous in the first place: Marlon Brando, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, and even the Marlboro Man. Savvy counterfeiters put American hardware and back-pocket stitching on Soviet jeans and sold them at inflated prices; customers didn’t care, as long as they could fool their friends. In Italy, the second-most popular jeans after Levi’s were knockoff Levi’s. It wasn’t just about wearing denim; it was about looking like The Boss.

Bruce Springsteen’s 1984 Born in the USA.

In the late 1970s, lawmakers came close to conceding completely. Hungary partnered with Levi-Strauss to open a new production plant and the factory met enormous economic success. By 1979, Blue Bell had signed a science and technology cooperation agreement to produce Wrangler blue jeans; after more than a year in talks, it seemed that Moscow would have its own American denim factory. But Jimmy Carter’s boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics halted the talks altogether, with Levi-Strauss’s director saying, “No U.S. team, no jeans,” and it wasn’t until the Iron Curtain came down nearly a decade later that brand-name jeans were readily available in Russia.

The inherent glamour of jeans undercut cultural propaganda, as well. Soviet TV programs selected footage of the worst parts of America to air in the Motherland as an argument against capitalism, but one Russian blogger remembers his reaction to film reels of urban poverty: “Even the homeless people in the West wore [jeans]. So, the wheels of Soviet minds turned, these people couldn’t be all that poor and miserable if they all wore the pants which we couldn’t afford!” An embassy worker remembers Soviet questions changing over the years from “Why [does the United States] treat African Americans so poorly?” to “Isn’t it true there are stores where you can buy 16 brands of blue jeans?”

Former President Jimmy Carter wearing denim on the Tonight Show. Image courtesy: The Guardian

When the Berlin Wall came down, Rifle Jeans opened a store in the Red Square; an Italian company began to manufacture Perestroika Jeans. In his book Jeans, James Sullivan quotes the president of the Denim Council describing denim as “a magnificent flag that says ‘USA’ to the world at large.”

Whether that flag was auspicious or ominous was a matter of perspective, but in either case it meant revolution: for young Westerners in pursuit of free love, or for young Soviets in pants that were worn, as Niall Ferguson points out, by every American president after Richard Nixon.