Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

Workwear, sportswear, mil-spec: these are all words that convey a sense of utility – purpose-built, hard-wearing clothing to get a job done. As I’ve written before, these are all things that have entered into street culture exactly because they are things that were functional and affordable. My first exposure to Carhartt was a blanket lined coat from the old Canal Street Jeans in Soho – workwear wasn’t a thing back in the mid 90s, but it was affordable, heavy duty and perfect to fight off the New York City winter. About that time, I remember buying a surplus French F2 coat for $15 at a store on 8th Street. It was suitably durable and I wish I still had it today. With its subtle waist suppression and lapels, it’s still probably the most refined military coat you can find these days.

Fig. 2 – French F2 Jacket (via HNP Whim)

These days, we are fortunate to have a wide range of beautifully constructed options in these categories – whether a pair of unsanforized duck canvas pants, cutting edge sportswear to meet the demands of elite athletes or a reversible military coat bonded by the same agent used to contain nuclear leaks after the meltdowns at Fukushima. I have no doubt we have lived in a golden age of functional menswear which looks and feels great.

Along with the re-emergence of menswear classics comes the inevitable re-appropriation by high fashion brands. I first started thinking about this after I bought the Visvim Black Elk flannel shirt at the top of this page, two years ago. As with most Visvim pieces these days, it is loaded with details – distressed Giza cotton flannel, skein-dyed indigo and finished with vegetable ivory buttons and a leather tag on the back. All those details come at a price and I found myself waiting for some kind of special occasion to wear it. And then I thought, what the hell kind of special occasion am I waiting for? It’s a flannel shirt, for crying out loud. After which, some kind of buyer’s remorse kicked in – was I going to sell it? Surely I could make only a fraction of that price back. And if I wore it, wouldn’t it decrease its selling value when I did go to sell? I’m not proud to have had these thoughts, and I froze.

After some time, I realized I was looking at it the completely wrong way. If you’re going to spend that much on a flannel shirt, you have to check any notion of utility or value at the proverbial door. When I bought that shirt, I was entering the luxury zone – an alternate reality where the utility of something is completely divorced from its price. It’s a great piece but not three times better constructed or fabricated than an amazing 3sixteen flannel I bought last week for a fraction of its price.

Fig. 3 – 3sixteen Crosscut Flannel. Image via Cultizm.

So why did I buy it? I’m honest enough with myself to acknowledge that marketing played a big part – as Dana Thomas observes in her wonderful book Deluxe (The Penguin Press, 2007), luxury conglomerates have profited more from marketing than actually making goods in a time-honored tradition (in 2015, the marketing budget for the largest luxury conglomerate in the world, LVMH, stood at an impressive $4.6 billion, or 12% of their revenue). And, as W. David Marx acknowledges in his instant classic Ametora (Basic, 2015), it is an aspect of brand ownership at which Visvim’s Hiroki Nakamura excels. I don’t want to say that Nakamura is misrepresenting anything about his products, or cranking up prices to add to profit margin, but my point is that he is skilled at selling them for the increased prices they currently command – and much of that is due to the stories he’s able to tell about the pieces.

Other examples of this phenomenon include luxury takes on athleisure – $1,575 cashmere leggings from the Elder Statesman for example. I’d like to think we are at peak athleisure (or valley, depending on your perspective) – but with the casualization of society, I wouldn’t bet against it.

For me though, the piece that sums up this trend is from Yeezy Season 1 – what appears to be a garment dyed MA-1. The details look to be dialed in and kudos to anybody who buys it and loves it, but for me it seems like a displaced soul inhabiting somebody else’s body. Maybe I’m skeptical because the Buzz Rickson version should be in the freaking MoMA collection for design.

Fig. 4 – MA-1 jacket by Yeezy Season One. Image via Ssense.

I am not singling out Kanye (there’s probably a good dozen of $2,000+ designer MA-1s out there now) and I have nothing against any of the brands referenced above. The dialectic between so-called low fashion and high fashion has become so entrenched in fashion today that it’s more like dialogue between two siblings that get on each others’ nerves every once in a while.

If I have a concern it is that having gone through a luxury trend cycle, there will be a backlash that many brands our community loves and respects will feel – brands that have great integrity and sense of context. Here’s hoping that our tribe will help sustain them no matter where this is all going.

I finally did wear that flannel, by the way – to a four year old’s birthday party in a fitness center. To paraphrase Maya from the movie Sideways – the day I wore that flannel was all I needed to make it a special occasion.

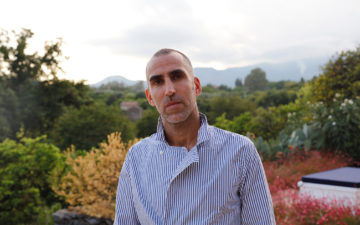

Fig. 5 – Black Elk in the wild