Few people become commercial and artistic titans in this industry. The vast majority have to choose between financial and creative success with their designs. Donwan Harrell is one of the fortunate few that really can have his cake and eat it too.

Over the past two decades, the founder and creative director of PRPS has positioned his brand to translate his deep passion for vintage workwear to a widespread audience. PRPS is everywhere, from the mainline to the Goods & Co. sub-label to the ultraluxe Noir jeans.

I had the opportunity to chat extensively with Donwan about everything from his love of vintage, his personal discovery of Japanese denim in Okayama, and where he sees the greater denim market moving.

David Shuck (Heddels): I’m in the offices of PRPS with the founder and designer of PRPS, Mister Donwan Harrell.

Donwan Harrell: Hey, great to meet you.

H: Yeah, great to meet you too, thanks for your time.

DH: It’s a pleasure to be doing this.

H: Oh pleasure to be here. People who are reading can’t understand the temple of vintage we are surrounded in.

DH: Well I appreciate hearing that. I’ve spent a lot of time collecting and it’s nice that other people appreciate it.

H: Yeah, and there’s probably more deadstock that I’ve seen here than just about anywhere. And you’ve got things going back to buckle-backs like Lee Riders and a whole bunch of other vintage and faded pairs. It’s really impressive.

DH: And without it, I couldn’t do my job, that’s for sure.

H: So as you were one of the first people to use Japanese denim and Japanese production in the United States, and if you’ve been paying attention to denim in the last decade that’s sort of been exploding.

DH: It’s exploded, yes. And I like to look at us, or myself, as definitely being a pioneer in introducing the fabrication to the US and replicating a vintage style using Japanese fabrication and selling it to some of the better stores in the US. As well as Europe. So definitely helping pave the way for a better quality of denim in the US.

H: So as a pioneer, as you say, how did you get exposed to the Japanese production, Japanese denim if you were the first to find it there?

DH: Yeah, well it’s a bit of a long story that I’m going to try to consolidate as best as possible. But at that particular time, I was living in Asia. I was living in Hong Kong and Japan, and headed up the OTS (team sports) category for Nike in Asia. And so with that being said I had to design uniforms for a lot of the different teams they would sign on, and one of the teams was the Blue Waves, which was a baseball team in Japan. And it was my first time being exposed to Japanese baseball. And to make a long story short, I had to study Mizuno, which was a primary supplier of baseball uniforms in Japan.

H: The shoe company?

DH: Mizuno did baseball uniform gloves, outfits, shoes, everything. They’re like the Nike of Japan. And they’re very, very much about quality and the athlete and performance. And you don’t realize that, living in the US, because you’re engulfed with Adidas and Nike and Under Armor or what have you. But there’s a lot of great small performance companies in Japan, and so on that assignment, I had to study what was currently on the market that I had to kind of study to do my uniforms for Nike.

And that’s when I realized how intricate the craftsmanship was that the Japanese were performing. In comparison to what we were doing as a company in the US. And I was like wow, having the pleasure of living there at Nike, seeing this first hand in Asia; it sparked my attention in wanting to do more research at some of the other companies that I hadn’t been exposed to. And I remember my first trip to the American Village in Osaka in the early 90’s, and I saw all this double-X style denim Levi’s that was being replicated by these small companies that I was just like floored. It’s hard, it’s crisp…

And again, you have to understand this was many years ago. In the US, the premium brands didn’t start until 2002, 2003. And we’re talking about women’s. There was only about Seven [for all Mankind], Diesel, and Lucky. This is before Lucky was bought. So this is before anybody had or was even thinking about premium jeans for men.

So seeing those big, crisp, hard denim items was a throwback for me, because I remember them as a kid because my mother and a lot of my aunts worked for Osh Kosh manufacturing overalls in North Carolina. And I remember everything was hard and crisp, so it kind of hearkened back to my childhood. But it intrigued me, so I wanted to ask them more about it.

So I started to ask a lot of the different stores and the denim companies why were they doing this, what was the purpose, where did it come from? And it was an eye-opener seeing these old companies. There were so many brands, but Osaka was just an incubator of all of these great Japanese denim companies at the time (related reading: “The History Of The Osaka 5“). It was my first time seeing them all clustered into one facility.

And I remember the one store Nylon, and it’s out of business right now, and I don’t know if I’m talking too much because I can really run…

H: Oh no, no, one of our writers has spoken extensively on Nylon and how much he enjoyed it before it shut down.

DH: Oh my god, Nylon was the crème de la crème of stores if you were a denim head back then before it closed. You could buy all the Snake Eyes, all the Real McCoy, all the, I mean I can’t even remember all the denim brands back then, but they had a room with every small tiny denim company on a wall. Andwhat the, you know, the Union Special machines and a single needle machine in a corner for all the repair and hemming, and you could pick from a cluster of maybe about thirty small companies, which jean you want and try them on, and you could learn about this.

And they had all the varsity jackets, all the leather jackets, it was like everything that you would, it was really like denim porn within this one little studio. And it was so sad that it, you know, it went bust, and it stopped because there’s nothing like it today in Japan where you have one store that personified everything you could think of when it comes to Japanese American culture.

H: It was there for you to cut your teeth in vintage.

DH: Yes, it was definitely. And I still remember to this day what I ended up buying, my first two pairs of jeans was a pair of Denime and a pair of Evisu. And again this is not the Evisu that you think of in the US.

H: That was still Evis back then yeah?

DH: Yes. And I bought a pair, and I remember I had another company trip to London because I had to design uniforms for the World Cup many years ago, and I went to a store called Duffer St. George, and the owner of Duffer St. George was a Japanese denim fan. Again, this was the 90s, mid-90s. And he was actually buying them, boxes of them, bringing them to a store in London, this is before any Japanese jean was in Europe, and he was cutting off the red label and selling them on a table at Duffer St. George.

And I was like, “Wow you know about these jeans!” And he was like, yeah, you know and I met the guy at Pendergrass who was one of the co-owners, and it was just nice to see somebody else that had become accustomed to seeing that kind of quality. And I knew right then and there I wanted to be in that game. I wanted to manufacture my own. And so that’s when I had the energy and the ingenuity to go back, to speak to these guys to find out where was the best place actually to do the manufacturing. And they all pointed to Kojima, which was in Okayama, Japan.

So I went to Kojima, had a couple of meetings with a few people, they recommended a few guys that I should work with. I went to those guys and, you know because there are a couple of different steps in the process. And not just manufacturing–doing the cut and sew, meeting the mills, and meeting the washing facilities, and that’s how it got started.

H: What were the people running the mills and the production companies, what were all these very traditional Japanese craftspeople, what was their reaction to an American entering their world?

DH: Really difficult back then, very difficult. They were a little bit shocked that I even knew about it, you know? I always, and I’m not sure if this is necessarily a good thing, they say it was a bit of a triad. Because it was all interconnected and they all knew each other, and like if I was at one place. If I showed up in Japan and I was at one mill they all knew. So by the time I went to the other mill they had already known and talked to each other via text or a call, hey the American’s here.

But you know, I got used to it, and they got used to seeing me, you know, every year, multiple times a year after that. And it was almost kind of like family oriented.

H: But it was still uncharted territory at that point.

DH: And they were just really suspicious about why am I here and why do I want to do this type of thing. Because you have to understand for them, it’s all about tradition. They had a really strong love for the product, and the fact that I would want to go there and make it and then ship it to the US, they were worried that I was going to make it too big and too commercial.

And I promised them; I said I’m going to keep it really high-end, only to select stores, and don’t worry about that. I won’t give you more than you can handle, but I’m going to keep it here. Like the fabrication here, the sewing here, so on and so forth. And after about a year they decided to say yes. But it was a communal yes, meaning like it was a combination of the wash factory, the sewing factory, all said yes at the same time.

H: You had to get the whole package deal.

DH: And it was, that’s why I call it a triad. But you know what? In the end, I’m incredibly grateful, and I have been very fortunate after all these years. I have the same sort of relationship that I have with them today.

H: So it just took that one year of persistence that paid off.

DH: Yes, because no one was doing it by that time. I mean they had a lot of little local domestic companies, but no one was doing that sort of thing back then.

H: But how did you imagine the American market would react to it? Because that was your plan, to bring it back to the States?

DH: Yes. At the time that I brought it back, I remember doing my first show and the funny thing was Rogan’s launched the same year at the same show. And you know he was using a lot of Cone [Mills denim], and he was using a company called Sights, I think out of Kentucky, to do the washing. He was doing like the whole you know engineered seams and things of that nature, but it wasn’t in a purist form like I was trying to replicate. Like the early Levi’s and Lees that I saw back in Japan. Totally different, and it was raw. There was no wash.

And to teach the market, the retailers, why this was so expensive was really difficult. It was difficult because there was nothing like it on the market at that time. And number one, me justifying it saying it’s made in Japan, I’m using this piece of goods, it’s selvedge, and then you have a guy down the aisle selling wash jeans, with all this character, with the twist seams. To them, they say they saw the value [in the washes]. So it was very slow in the beginning.

Now today it’s very commonplace. We say Japanese, we say selvedge, we say this vintage piece inspires it, they love it. It’s a great story. But back then in the late 90s it was tough.

H: Because made in Japan back then didn’t have the same cache at all.

DH: There was nothing.

H: It was looked down upon, sort of like made in China was the same it is today?

DH: Exactly. For them the average customer, it doesn’t matter if you’re European or American, Italian meant quality. Made in Italy. Made in Japan though was like a whole other level of luxury that they didn’t know about. Today it’s different, but back then they had no comprehension of what that kind of luxury was.

H: Oh, how did you get the capital together to run this first season of jeans?

DH: Oh that’s a story in itself.

H: Yeah because you’re this crazy guy that loves Japanese jeans that no one else had ever heard of, I imagine getting funding together to do a run of this stuff because it’s a very expensive fabric, expensive production…

DH: I pretty much had to sneak it under my partners’ noses. When I told them conceptually about the concept of the company they were adamantly no, I don’t want to do anything. That’s not going to work. You’re crazy. Because I had another company that was a blooming company at the time that was a lot more commercial.

H: What were you making then?

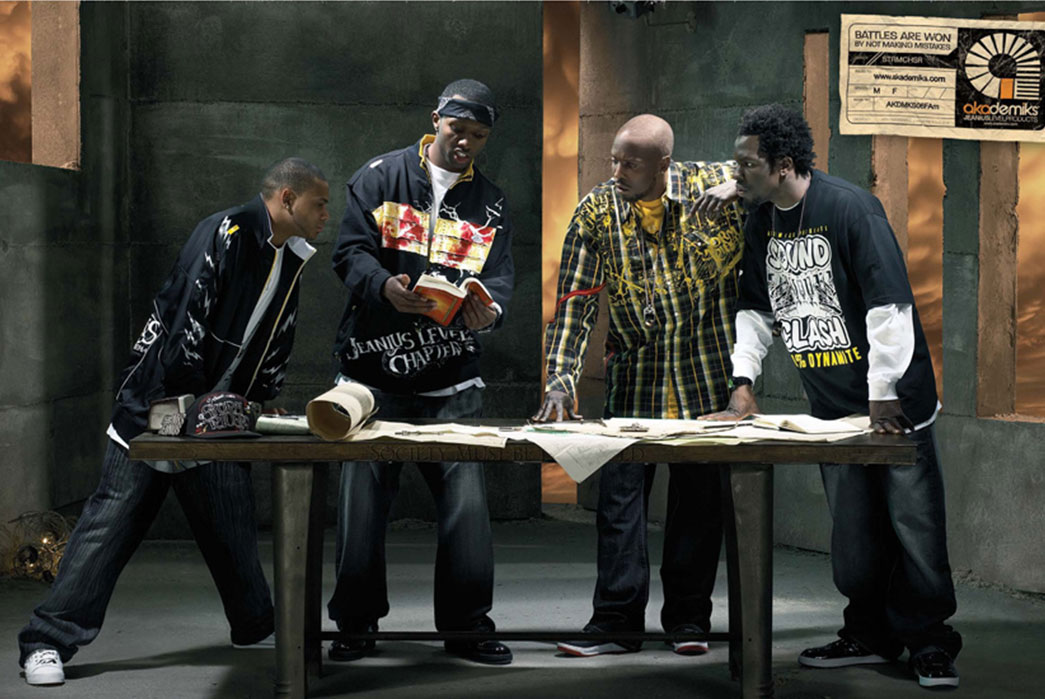

DH: That was a streetwear company called Akademiks many years ago. And they were adamant that I don’t do this [start PRPS]. But you know what? I’m a very determined guy, and I knew in my heart that this would work. I think the US needed to be introduced to this type of quality because it’s something that we created, that someone had mimicked, and we should bring it back to the US actually to showcase it back to America so that the level and quality of the American consumer can get raised.

A lookbook photo from Akademiks.

So I went to the factory, and I promised the factory they were getting made. I’ll get paid. And I remember once the stuff was shipped I had it sent to my office directly and not to the warehouse.

H: So the partners still didn’t know about it?

DH: They still didn’t know, because if it goes to the warehouse, then it gets checked in the database. So I had it shipped directly to the office. And I remember unpacking it, putting it in a suitcase, and I went with my wife and a few of the employees to Europe. Because I had received orders at that time because I had shown it in a show, and so I had actual invoices. And then Duffer St. George, Liberty Department Store, and a few other stores I hand-carried the jeans, the product, to the stores and dropped it off myself.

It was a great story because the fact that I had to do this underhandedly, and when I came back I told the partners I had orders. I shipped it to the stores; I told them what stores and they were like, “You actually got orders for this at Duffer St. George and Liberty Department Store and Harvey Nichols and Selfridge’s?” And I’m like, yes. These were the top stores at the time because I launched it for Europe first. And they were like astounded, like well okay let’s entertain this. Let’s see. I didn’t think you were going to get any orders. And that’s how I was able to kind of coax them, but I had to be very sneaky and underhanded, unfortunately, and I was very fortunate to have partners like them to be patient for it. And that’s how it started.

H: Well it’s been vindicated since then.

DH: Yes. Yes.

H: So the first collection was raw primarily.

DH: Yes, it was raw, and it was based on a combination of Italian military World War 2 and American World War 2. So I had certain types of jackets that I had put in herringbone denim, and I did it as raw, and I did it as a rinse. And with very mild grinding, but I wanted that look of like, you know, those M jackets, those M-type jackets and the cargo pants, and this herringbone denim with just a rinse. Because I love the look of it. And even today just the idea of it sounds good, you know?

H: But after that first season, where did you think it was going to go?

DH: You know, I had no idea how far it was going to go. I knew based on the price it would only be able to go into premium stores, and so I’m not sure if a lot of people will remember this, but there was a store called Union in New York before the Union in LA. And that was the first store in the US that I shipped. Then I started shipping Barney’s, and it was starting to carve itself out as this is the type of store and the type of customer that’s going to buy it and lo and behold it was, there you go, I had a marketplace for it.

Again, the whole selvedge and raw scene was still really new, but these stores had a little bit of faith in it, and it worked, it worked.

H: Yeah how did they go about educating their customer on it?

DH: They didn’t. There was no education.

H: They just put them on the rack and said these are the jeans this season?

DH: That’s pretty much how it was, and it worked. You know the folded back pocket, which was one of the primary staples, within the line, and I think that kind of attracted people heavily instead of just a traditional five pocket. But the fact that I took the back pocket and folded it just to give a bit of a twist from a traditional five pocket.

H: Yeah and got your pen pocket back there.

DH: Exactly. And so that kind of helped move it, it made it a little bit different.

H: But from there like most of the collection afterward has been primarily washes.

DH: Yes.

H: What was the transition between those two?

DH: That was the actual second season. And the second season in the midst of working with the cut and sew factory and the wash factory I saw some cool experimental development in washing. I used to bring a lot of military vintage to mimic and replicate. And I decided you know I’m going to throw in a jacket, I’m going to throw in a jean, and I’m going to try to replicate the look and character of that vintage jacket. But at the time that was just an army green surplus fabrication. But I wanted to do it in denim and see how it would react, but just to get the same sort of character like that.

Took it to the show, and they clung to it, it was almost like eye candy for them. And I hadn’t been able to turn back. That has been primarily what they have wanted from me since that day from that second collection.

H: So the transition there was basically like the first collection you’re just trying to recreate the garments based on their construction details and their fabrics, and the second collection was taking it a step further to recreating the wear patterns and actual distressing on it.

DH: Exactly, but I had no idea that that’s what they were going to gravitate towards. And so, you know, all these years later and when we see PRPS it’s primarily just washed jeans. Beautifully washed jeans, but unfortunately, the whole idea of me introducing raw and Japanese fabrication and selvedge has kind of gotten lost in the midst of all of that.

But we always try to introduce to the stores every season heritage styles in raw and rinse, but it’s really up to the store to decide what they want to buy. I have no control over it. They buy certain brands based on what they want, how they want that brand perceived in their store. You know? I’m just grateful to be still around after all these years offering beautiful Japanese denim to the general public.

H: So it’s just exploded since you introduced those first washes. And now you’ve got three lines, you’re all over the world, you’re doing quite a few collabs. What was the process like in I guess segmenting out your line into PRPS, Noir PRPS, and PRPS Goods and Co.?

DH: That’s correct. The first line was PRPS Japan, which was just a rising sun image with a Masai warrior. The first denim was from Kuroki, and they made me a specialized denim with a purple selvedge. Because I wanted a color that was different than the traditional Cone Mills red.

H: Which is what they were all trying to emulate.

DH: Of course, because that’s the original, Cone invented the whole red selvedge concept. And I wanted to do something that was going to mimic what represent us, which was purple. Because purple to Asia, to Japan meant royalty. So I said I want to do purple, and it was going to be very distinguished from everybody else that was doing a red in Japan. And it was very well received, but not only that the cotton that was being procured by Kuroki at that time was from Africa, Zimbabwe.

Those became the details of the original Japan jeans with the rising flag, which is Japan, which is me introducing Japan to the US, and the Masai warrior, the African image mixed in to create this beautiful jean that I was going to sell to Europe and the US. And that’s how all that came together. Me teaching them through the label, through the package, through the jean, all of this.

PRPS’s signature purple selvedge.

And that was the original Japan jean. After that, then it became about all the heavy washes, and people still didn’t understand the selvedge at that time, so I wanted to come up with a line that was all selvedge that was going to show them in the washes. And that’s when I came up with the Noir line, which is the crème de la crème. Which is the selvedge, the washing, the fabrication, and all that. So I diversified that fabrication to Nihon Menpu, to Colette, to Kaihara and a few other mills outside of just Kuroki, which was a Japan line. And that has been received well, and that’s what you see David Beckham, Tom Cruise, Gerard Butler, you name it, every celebrity seems to have gravitated towards those really high-end styles that you see. And Fred Segal, Ron Herman, Politics, you name it, American Rag, all the high-end, Bergdorf Goodman stores.

And then two years ago I saw that stores like Uniqlo, the Gap, stores like this, starting to introduce selvedge at a price–49.99, 59.99, using Japanese fabrication. Taking the bulk of the mills and introducing it to the masses, to the community. I knew I needed to come out with something to just be able to stay in business and be competitive. A segment of my line that was going to be commercially accessible to the general masses, but still keep it Japanese. And so what I decided to do is utilize Kaihara denim, which is beautiful Japanese fabrication. Many Japanese fabrics suppliers have a hard time shipping to different places in the world so that you have access to it, so Kaihara’s really really good at that. And I decided to create the Goods line, PRPS Goods and do washing in Europe. And that line has been phenomenal. We sell it at Sak’s Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdales, Nordstrom’s, Neiman Marcus; it’s been great. So that gives us – that gives me three tiers.

I like to see me as a bit of an incubator of Japanese fabrications to the general public for different pockets of communities based on what you aspire to have.

H: And expose people to the higher quality of what is Japanese fabric so if they dig it they can sort of move up the line as they see fit?

DH: Yes, bingo, bingo. It’s just like a BMW, you know? You have your 125 and you have your 325, and you know, not everybody can afford an M3 or an M6, or an M5, but they have different segments if you want to buy into the brand. And I modeled it like the vehicle where there are pockets that you can buy into.

H: Do you see any other segmentation coming soon, or is this the perfect mix?

DH: Hopefully women’s. Which is always a very difficult consumer, because, and I’ve seen RRL try to outfit women in selvedge jeans, and then they stop the division, and then they start it up, and then they stop it. It’s difficult, it’s very difficult.

H: Because you can’t do that busted selvedge outseam?

DH: There you go.

H: You have to have more cuts in the leg to accommodate that fit, and it takes more than, any guy can pretty much fit into any one of four fits. That’s not the same in women’s at all.

DH: That is correct. Us as men, we just get up in the morning, we take a shower, we put deodorant on, and we put our jean on, and we’re out the door. Some of us do our hair, some of us don’t do our hair. We’re very low-maintenance guys.

But women are a little bit different, from what I’ve seen, where they’ll take a shower, and they put lotion on. And I’ve been told this by a number of women: well you guys don’t put lotion on like we do. You just take a shower, and you just put your jeans on, you go. We put lotion on, then we put our pants on, and if you wear them every day with the lotion that affects the smell of the actual jean. And so it’s a lot stronger than what you find in a guy’s jean.

And I never really thought about that because again we take a shower and put our jeans on, and we’re out the door. But they’re like oh we put lotion on, and that gets into the jean, and it’s just more difficult. And I can see that being part of the problem, not just you know the busted seams but for them, it’s a little bit different. You know, we see the images of Marilyn Monroe in jeans and Lee jeans and stuff or in Levi’s she probably wasn’t doing all that. But today, women can be high maintenance. You know? And so I totally comprehend, and that might be why they prefer some of the what I call microwave jeans. Which is the stretch jeans and you buy one and two months later you buy a new one and you throw it out because the elasticity’s out of it.

H: Is that something that’s in development right now?

DH: I’d like to try to figure that out. I love challenges, and I’d love to provide them with something that they can take pride in just the way we do, that they can wear out and see the characterization develop over years of time with spending time with just one pair of jeans. That also that they can say it fits, and without the elasticity.

I’ve tried once before, but I had decided to put it on pause to develop my Goods line, but I want to go back to it.

I always house a box of women’s selvedge jeans in the office that I give away to the buyers. And they seem to love it, you know? But I want to have it as an actual line of business at some point.

H: As if they can’t love it then there’s no reason they’re ever going to put it in the stores.

DH: Exactly, exactly.

In Part II of our interview, we cover Donwan’s passion for vintage workwear, the shifting relationship between American and Japanese culture, and what he sees for the future of denim.