Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

Let’s face it – the apparel, footwear, and accessories featured on this site are pretty awesome, but not necessarily affordable to a large part of the US population. Most of us probably understand that there’s a reason behind the cost – usually a combination of superior materials or a labor-intensive manufacturing process. These things often add up to a good story, and it’s a story we really have to tell to educate others on why we’d pay $300 for a pair of jeans. Why? Because I’m probably not the only person who’s heard this question:

“Why would you pay that much for a pair of jeans? They cost $20 at Walmart.”

I was thinking about this a year ago, and I realized that I had a much better understanding of why a pair of jeans could cost $300 than how they could cost $20. If I mailed a pair of jeans to California, that alone would cost $13. So how can anyone make money at such a low price? I started to suspect that the hypothetical question of “why expensive jeans” was completely backward and sent out this tweet:

Why does everyone ask “why is this so expensive” instead of asking “why is this so cheap?” @selfedge

— R. Lim (@psf1516) August 23, 2015

The response was really good, so I figured if I came to understand the economics that others might be interested too. And what I found out ended up equally surprising and troubling – the cheap price of the jeans exacting a heavier price. I have a lot to share from my research, so I’ll be doing this as a two-part piece, with the next part published in August.

Jeans – For Every Occasion

Once a working man’s staple, jeans have become ubiquitous in almost any setting. Depending on the cut, color, fabrication, and trim, they can be equally home on a factory floor or fashion ball. In a sign that they’ve become default casual wear, classic brands that use all-American spokesmen like Brett Favre and Dale Earnhardt Jr. now advertise their jeans’ comfort rather than durability – with a bit of synthetic stretch in the mix, they’re as comfortable as the athleisure sweatpants that they are now competing with.

Fig. 1 – We know they’re rugged, but are they comfortable?

Now that jeans are more fashion than utilitarian, there’s been a corresponding increase in consumption to keep up with the latest styles. Americans buy an average of almost two pairs of jeans a year, to the tune of 511.5 million pairs in the year ending April 2015 (source: The NPD Group, via WWD). And we own an average of 6.7 pairs of jeans per person in the US, down from a remarkable 8.2 pairs per person in 2006 (I’ll talk about where those 1.5 pairs went in next month’s column).

Those 500+ million pairs of jeans represent sales of $13.3 billion – if you’re handy at math, you’ll notice that that’s an average of about $26 a pair. But how do jeans companies manage to do that?

Driving Costs Down

The answer is largely overseas manufacturing, where labor costs and oversight are lower. China is a huge industrial power, but a casual browse through a big-box denim section turns up manufacturing in countries like Vietnam, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Mexico and the small African country of Lesotho represented in that department – Levi’s factory list alone covers hundreds of suppliers in 38 countries. And the Chinese have started to export their manufacturing expertise, owning a number of factories in Africa.

We’re trained to expect quality and convenience at a low price, so what could be the downside of such affordable jeans? With constant price pressure and razor-thin margins (around 3-5% in China as reported by Bloomberg News in 2010), factory owners are highly incentivized to cut corners on safety and working conditions. In 2013, garment factory workers in Bangladesh were evacuated from the eight-story Rana Plaza building after cracks in the building started to appear. The building was deemed safe by its owner, who urged the workers to return the next day. They did, and more than a thousand died in the resulting collapse, which also injured 2,500 more in the worst garment factory disaster in history. To get a sense of its scale, it eclipsed the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 (the worst industrial disaster in the history of New York City) with seven times the number of dead and forty times the injured. Just yesterday, Bangladesh indicted 41 of the people involved in the collapse on murder charges.

Fig. 2 – The collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013, via The New York Times

Another huge concern is the living conditions of the workers. Factory wages tend to track with the minimum wage, which in the developing world is often a fraction of the “living wage” deemed necessary to have common human needs met (food, shelter, clothing). It’s also sometimes below what’s called a “subsistence wage,” a lower number at which the most basic human needs are met. I don’t know about you, but it seems to me as if something’s very wrong if that very low bar isn’t being met.

A number of companies appear to agree (or at least say they do) and have focused on exceeding the minimum wage for factories where they have operated – in his memoir Shoe Dog, Phil Knight claims that he once tried to raise factory wages in an unnamed country and found himself ordered to cease and desist by a government official. Apparently, it was higher than a doctor’s wage there. And in 2009, fast fashion retailers, big box stores, and other larger brands wrote a letter to the Bangladeshi government asking them to raise the minimum wage, citing that it was below the World Bank poverty line (despite having exerted pressure to reduce prices from their suppliers there the year before).

Whether or not you believe Knight or these retailers, it shows how complicated the issue is – especially since these factories are often not owned by the companies to whom they provide services. While there may not be much we can directly do about this (which I’ll talk about next month), but I do give credit to brands that strive to provide transparency on these issues and to the reporters that shed light on where they may be falling short of the mark.

In case you’re wondering what that World Bank poverty line is – as of 2015, it is $1.90. Per day.

Environmental

The denim you wear comes from everywhere. Cotton is a commodity product and denim doesn’t require specialty high-quality, long-fiber cotton. An average pair of jeans might contain thread from four continents. Cotton is a water intensive crop and requires a lot of intervention when grown at scale – even though it uses 2.4% of available agricultural land, it’s responsible for 24% of insecticide use and 11% of pesticides.

Apparel is the second most polluting industry (second only to oil), producing 10% of the world’s carbon emissions. A company called Avtex Fibers that specialized in manufacturing rayon in Virginia was permanently shut down in 1989 for water pollution and was listed as an EPA Superfund site until 2014. Health officials still warn against eating certain fish in the nearby Shenandoah River due to PCB contamination. And it’s not just synthetic textiles – in 2010, the London Times found that a factory in Lesotho that was supplying Gap and Levi’s had been dumping untreated, polluted wastewater. It leaked into the water table and stained the mud on the banks of a river blue.

Fig. 3 – Untreated denim dying wastewater in Mexico (via The Guardian / Reuters)

The Upshot…?

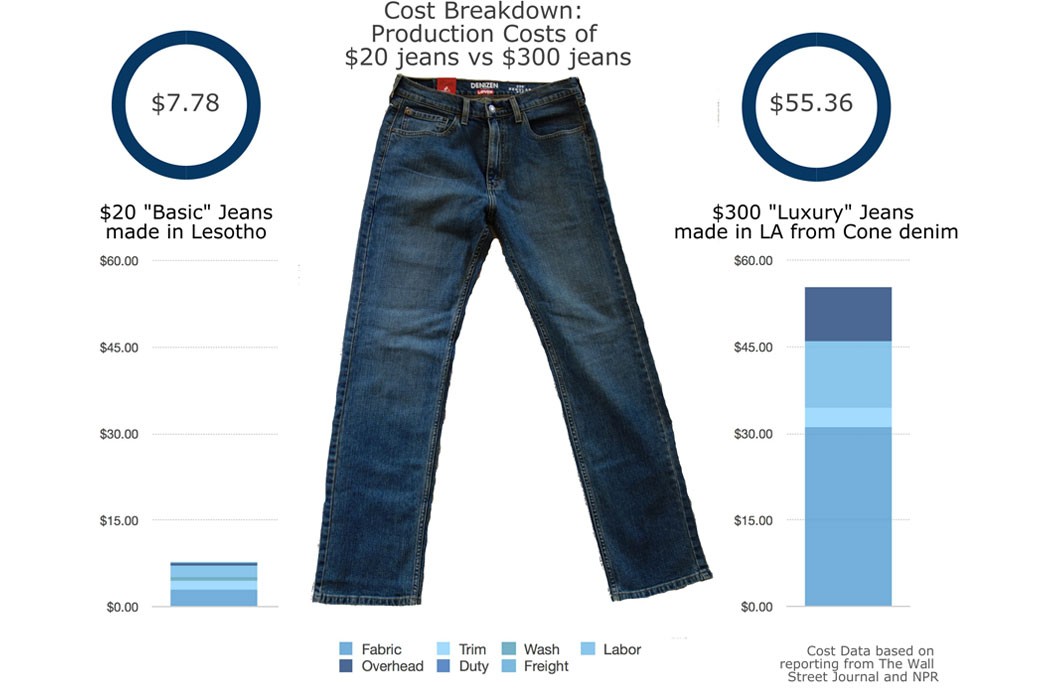

So now that we understand how it’s possible for a pair of jeans can cost $20 and how that figure doesn’t include the human and environmental costs associated with their production, what are the actual production costs?

To start with, the production costs behind a pair of jeans that retail for $20-$30 are about the same. The total cost to get this kind of pair of jeans manufactured overseas into the country does not appear to vary in this low-cost price point – between $7.50 and $8 per unit. This includes fabric, hardware, labor, duty and freight. Chinese have the lowest production costs but are subject to a significant 16.8% import duty. Other countries like Lesotho, Haiti and Nicaragua have all negotiated duty-free imports into the US to make their apparel industry more competitive.

The fabric costs are about three dollars, which is maybe 50% more than what a pair of good pocket linings alone might cost. Selvedge fabric from Cone Mills might run about thirty dollars per pair, or ten times more.

Labor costs per unit are about two dollars, versus twelve dollars for a pair produced in Los Angeles (the denim capital of the US).

Overall, a made in the US pair of selvedge denim jeans from Cone Mills could cost about eight times the amount to produce than cheap jeans – and that’s excluding overhead like marketing, staff and office space for a brand. For smaller brands or those working with denim to spec, these costs are correspondingly higher.

Now What?

So what does this all mean? A combination of cheap labor in developing countries and a commodity crop has yielded a large production of jeans on a scale with both social and environmental consequences. And at such a cheap price, we buy pair after pair. But what happens when we no longer need them? That’s a story even more complex than the one above. It includes fake charities, African smugglers, old trade routes dating back centuries and an alternate universe in which the New England Patriots finished the 2007 NFL season 19-0.

To be continued in August…

References

Simply put, this piece wouldn’t have existed without the following (whose references I have made liberal use of):

- Elizabeth L. Cline, Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion (Portfolio / Penguin, 2012)

- Andrew Brooks, Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-hand Clothes (Zed Books, 2015)

- The True Cost, directed by Andrew Morgan (2005, Life Is My Movie Entertainment), Netflix stream

Prices for producing jeans come from:

- Christina Binkley, “How Can Jeans Cost $300?,” The Wall Street Journal. July 7, 2011

- Jacob Goldstein, “Global Poverty and The Cost of a Pair of Jeans,” NPR. March 3, 2010

Other references are below:

- industriALL global union, “Lesotho workers march for a living wage,” October 26, 2012

- Virginia Department of Health, “Fish Consumption Advisories,” March 29, 2013

- Sheila Macvicar, “Jean Factory Toxic Waste Plagues Lesotho,” CBS News. August 2, 2009

- Arnold J. Karr, “Could Women’s Jeans Be Making a Comeback?,” Women’s Wear Daily. June 10, 2015

- James Conca, “Making Climate Change Fashionable – The Garment Industry Takes On Global Warming,” Forbes. December 3, 2015

Please note – all links (and the Netflix stream) were accessible as of July 18th, 2016