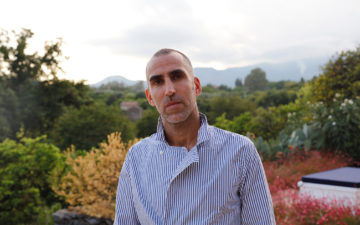

Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

I’ve written before about menswear standards – classics that serve as a blank canvas for designers and brands to express themselves. What’s on my mind these days is the plaid pattern known to Americans as “buffalo check” – a simple plaid made of two colors in a twill weave to make alternating boxes – it’s often red and black but can be any two colors.

It, and other plaids, are having another moment as menswear goes through an early Nineties throwback moment – a mishmash of oversized, big logo athletics and the flannel shirts echoing a grunge “look” from the underground music scene based in the Pacific Northwest that gave rise to bands like Nirvana. But the story of buffalo check goes back way deeper than most people realize.

Fig. 2 – Paul Bunyan statue, Bangor, ME (via Dutch Girl Chronicle)

Readers of this site are more likely to associate the pattern with its appearance on workwear, the corny lumberjack stereotype typified by representations of Paul Bunyan. This lineage is claimed by Woolrich Woolen Mills, who introduced the plaid in 1850. While they are careful not to specifically claim credit for originating this pattern in America, it’s featured in their company history and they seem to hold a trademark on the term. You can now find different variations on the Woolrich site, from flannel shirts to woolen shirt jackets that are proudly touted as Made in the USA – there’s even a dip dye version, representing the tail end of that particular trend.

Others may note an overseas origin, going back to Scotland where it’s a Tartan commonly referred to as Rob Roy. The simplistic explanation of a Tartan is a specific plaid pattern. Most of us are told they are used by clans in Scotland to denote membership or affiliation, but in reality their usage is much more widespread these days.

In any case, The Scottish Register of Tartans records its earliest known usage of Rob Roy as 1704, although ironically (or perhaps predictably) there is no evidence that the actual historical figure Rob Roy had actually worn it. Regardless, it is officially associated with Clan MacGregor. From this, you’d imagine this pattern was handed down from generation to generation in the Clan, so case closed, right?

Fig. 3 – Kilt in MacLeod Tartan, woven by Peter MacDonald of Scottish Tartans.

It’s here where the story gets interesting – while some Tartans have been around for ages, it turns out the practice of naming them and formally associating them to Clan identities is a relatively recent one, dating only as far back as the late eighteenth-century.

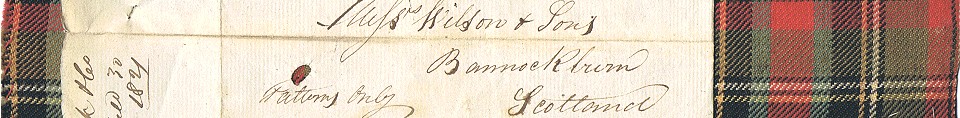

The reason for this is in large part due to William Wilson, a Scot who founded a prominent weaving firm in the latter half of the Eighteenth Century. As the demand for tartan fabric grew, they required newly emergent industrial technology to supply increasingly large orders. This drove a need for standardization, and as a result Wilson started to name patterns after towns, and then families. This practice culminated in the 1819 publication of an in-house reference manual called the Key Pattern Book – a sort of internal pre-Pantone reference to ensure a run of Tartan fabric would match any previously produced pattern of that designation.

Fig. 4 – William Wilson and Sons, Bannockburn (via Tartans Authority)

Simultaneously, a group of ex-patriate Scots organized as the Highland Society of London started to collect samples of Clan Tartans, in an act of historical preservation. Contrary to what you might expect, the Clan Chiefs encountered some degree of confusion in coming up with representative samples – apparently, there were enough patterns in use that there was little consensus on what a “true” Tartan was for some (if not many) clans.

Historically, it turns out regional availability may have been more of a factor in what Tartan someone would use for their dress than a specific pattern (the same was true of flannel shirts during the grunge era – while you might prefer one plaid to another, you weren’t holding out for a particular pattern, nor was there an Internet to search among thousands of options). In a further indication of the modern nature of Tartan association, there are examples of Tartans submitted for registration that were late eighteenth-century designs, woven by William Wilson. It seemed the equivalent of gathering historical New England wear and being handed a vintage Red Sox jersey.

A reasonable person might seek to connect these two traditions – American workwear and Scottish Tartan – and indeed, there are stories suggesting that the pattern was brought to America by ex-patriate Scots. In particular, it’s part of the founding story of a recent brand called Braeval, whose founder Gregor McCluskey claimed to descend from one such immigrant. But McCluskey himself says he was unable to verify the narrative. It’s smart marketing, but sounds more romantic than believable.

Fig. 5 – Buffalo Check as Queen Charlotte’s Check, via forever*cottage

And to drive the point home, buffalo check also appears as an American Colonial-era pattern – named Queen Charlotte’s Check after King George III’s partner. This would mean it has a completely independent association to either the American West or the Scottish Highlands – think of it as a bigger version of gingham. It wasn’t until recently that I realized I have a pair of oven mitts with the same pattern.

So what does this all mean? Maybe it’s helpful not to think about it through the straight arrow by which we often think of history. After all, the simplicity of the pattern itself is such that it’s available to any culture that can make a dye or two and the ability to weave twill. If you wear it as a kilt, it looks Scottish. If you wear it on a flannel, it looks outdoorsy. Or, you could end up with this choice piece from Ann Demeulemeester – a buffalo check on a gauze-like wool, made into an extra long shirt – half cardigan, half shirt jacket. It allows the house to demonstrate its unique, distinctly Belgian vision – a blank canvas for a romantic punk with a keen sense of drape.

In other words, maybe we should think of it as a standard.

Fig. 6 – Cooper shirt (via BVBA 32 / Ann Demeulemeester)

But wait, there’s more!

It doesn’t fit with the theme, but in this case I couldn’t resist. In my research for this piece I ran across various techniques of weaving kilts and stumbled across various selvedge techniques. There’s several of them, but the one that caught my eye was a herringbone selvedge, which can be done either with the same colors as the tartan or with the addition of another color (creating a selvedge mark). Check out the image below (and the bottom of the kilt pictured in Figure 3 above) and you can see the familiar saw-tooth pattern.

Just imagine: a buffalo check flannel with herringbone selvedge along the bottom of the shirt instead of a traditional hem…

Fig. 7 – Herringbone selvedge from a mid-Eighteenth Century plaid in the collection of the Highland Folk Museum (image copyright: Peter MacDonald, scottishtartans.co.uk)

Thanks to Steve Ashton at X Marks and Peter MacDonald at Scottish Tartans for their invaluable insights. The history of Tartan is a complex one; any mistakes above are mine and mine alone.