Happy New Year! Wait–you celebrate the New Year on January 1st? Not me–New Year’s Day always feels like the end of the something, not the beginning. After all the turkey, egg nogg and champagne, I’m left feeling run-down, not revived and ready for the start of something new. But the beginning of fall, back to school and the pumpkin spiceification of the known universe? To me, that has always seemed like the true beginning of the “new” year, summer’s frivolity behind me with the promise of new projects ahead, armed with a Trapper Keeper and batch of newly sharpened #2’s.

And of course, what better way to embrace the new than with a freshened wardrobe, and for most of my adult life in New York, that meant crisp oxfords from Brooks Brothers, a new tweed jacket from J. Press, and a reunion with old friends…the knit ties, khaki pants and cashmere sweaters that were once again front and center in my closet. I’ve always been a sucker for classic Ivy Style, and that’s why it’s been such a pleasure to spend some time with W. David Marx’s incredible book, Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style.

I received Ametora this time last year, and as I was writing my recent piece on Japanese Souvenir Jackets, I was reminded what an indispensable resource it is. This book is that rare example of both a wealth of information and an addictively page-turning great read, one still worth discussing now. As far as I’m concerned, a book like this will never get the attention it deserves, so consider this an early-bird-one-item-gift-guide for the heritage brand fan whose on your holiday “Nice” list.

There’s no denying that in the 1970s through the end of the millennium, we lost our way with classic American heritage and workwear. Thankfully, the always style conscious Japanese are here to remind us that you never really know what you’ve got until it’s gone.

According to Ametora’s back cover, “…cultural historian W. David Marx traces the Japanese assimilation of American fashion over the past hundred and fifty years, showing how Japanese trendsetters and entrepreneurs mimicked, adapted, imported, and ultimately perfected American style, dramatically reshaping not only Japan’s culture but also our own in the process.”

Nail = Hit On The Head, and considering this tome likely costs less than the belt loops on some of your favorite denim, it’s both a bargain and essential addition to the Asian Sub-Sub-Sub-Subsection of the International Sub-Sub-Subsection of the Heritage/Workwear Subsection of the Fashion Section of your home library. (Really, just me?)

- Author: W. David Marx

- Hardcover: 296 pages

- Publisher: Basic Books (December 1, 2015)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0465059732

- ISBN-13: 978-0465059737

- Product Dimensions: 5.6 x 1 x 8.3 inches

- Available from Amazon for $20.79

As the former editor of the street culture magazine Tokion (who has also had articles appear in GQ, Harper’s, The Fader and Nylon), Marx is that unique variety of writer who can take what could be dry and academic and make it approachable and a true pleasure to read. His writing does so much more than give us just the facts – he takes you on wonderful detours that paint a picture of the personalities behind the Japanese pioneers that spearheaded Japan’s take on American classics:

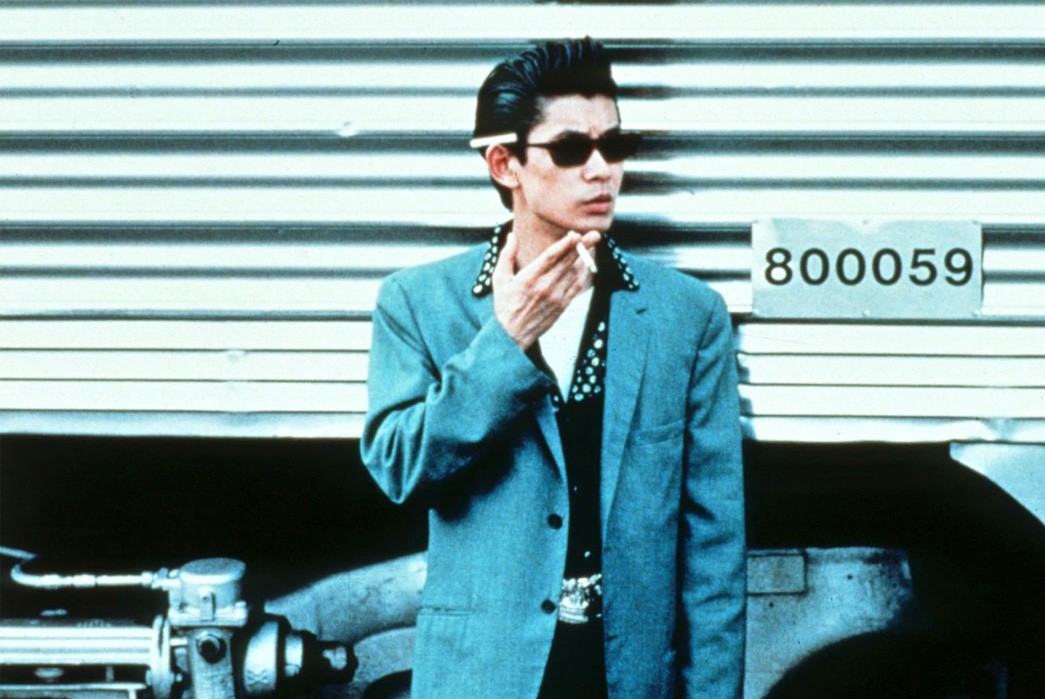

In 1982, thirty seven year old bar proprietor and fashion impresario Masayuki Yamazaki completed work on a five story, pastel art deco retail space called Pink Dragon right between the youth shopping districts Harajuku and Shibuya. The first floor and basement sold clothing and accessories from Yamazaki’s fifties-inspired brand Cream Soda. Upstairs was an American-style diner called Dragon Cafe, complete with vinyl leopard-skin couches and a vintage jukebox. Yamazaki lived in a luxurious apartment on the top floor, and he carved off the second basement level as a rehearsal space for Black Cats, a rockabilly band under his patronage. The swimming pool on the roof was a truly gratuitous luxury, seeing that Yamazaki could not swim.

Marx covers a wide range of topics, from the historical perspectives mentioned above, to the cultural significance of Japan’s obsession with preppy clothing, to why Japanese magazines are formatted like catalogs. (Who knew!) Along the way he discusses all the names and titles and brands that will surely send you down the rabbit hole to more reading/filling out those Subsections of your library. (C’mon, seriously, just me?).

Perhaps what I love most about this book is Marx’s ability to identify more than a few “absolutes.” When it comes to historical and cultural trends, it can be difficult or impossible for many authors to pinpoint the exact who, when, where, and why of an inciting incident…to point a finger at a tipping point. And while Marx is certainly respectful of the nuances of history, he is also able, in less than two pages no less, to lead us to clarity like this:

For many years, the Japanese were the world’s most passionate consumers of global fashion, but over the last 30 years the trade balance has shifted. Japan’s designers and brands have enjoyed significant attention from overseas audience, and now their clothing around the world.

European fashion insiders first fell in love with the exotic Japanese designer apparel – the boisterous Oriental patterns of Kansai Yamamoto and Kenzo Takada, and later, the avant-garde creations of Comme des garcons, Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake. By the first decade of the twenty-first century, hip-hop lyrics referenced Japanese streetwear brands A Bathing Ape and Evisu as conspicuous Accoutrements of a lavish lifestyle.

Meanwhile, savvy shoppers in New York’s Soho or London’s West End came to prefer Japanese chain UNIQLO over The Gap. Then, something even more extraordinary happened: the fashion cognoscenti started to proclaim that Japanese brands made better American-style clothing than Americans.

In 2010, people around the world snapped up reprints of the rare 1965 Japanese photo collection Take Ivy, a documentary of student style on the Ivy League campuses. The surprising craze for the book helped popularize the idea that the Japanese – like the Arabs protecting Aristotelian physics in the Dark Ages – had safeguarded America’s sartorial history, while the United States spent decades making Dress Down Friday an all-week affair. Japanese consumers and brands saved American fashion in both meanings of the word – archiving the styles as canonical knowledge and protecting them from extinction.

There is a small section of glossy black and white photos in the book’s center, and others scattered throughout the book, but I would have loved more pics, and some in color. (I’m a simple man – don’t judge me.) That being said, this is certainly the book that has best contextualized the Japanese appreciation and commodification of the classic and traditional American look…ametora. You’ll likely plow through this in a few sessions and certainly refer to it often, as it features an extensive section called Notes and Sources, a bibliography that is going to put a serious hurt on your Amazon Prime account, and an index that will have you flipping from back to front like a madman.

Ametora is published by the Basic Books imprint, and for the Heddels crowd, this is indeed a basic book for us all to own. And in judging a book by its cover, this one is swell – no dust jacket, a beautifully textured and graphic front and back, with indigo end papers and khaki lettering. Perhaps you should think of getting two copies so you can cross reference them on your shelves under both fashion and history? (OK, maybe I should talk to someone about this library thing.)