Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

Let’s address the elephant in the room, as it were – Made in the USA is a thing. And not just something the community of Heddels geeks out about, but part of a larger discussion about the future of manufacturing in America. Maybe I’ll get to that one later, but not today. Today, I want to talk about the tiny slice of Made in the USA that never quite left – the tiny plot of land in Midtown Manhattan, less than a square mile in size, known as the Garment District.

If you live in New York City and have a taste for high-end designer clothing, your first experience with the Garment District may have been through a sample sale held at a showroom. Or for fans of Project Runway, you may know it through the cast’s obligatory visits to Mood Fabrics. For all the glamour of the fashion industry, it’s a deeply functional and industry-focused place.

Today’s Garment District is an echo of its past – rooted in a garment manufacturing industry that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century. As the East Coast gateway to immigration, New York was perfectly placed to capture the influx of skilled European immigrants, who fueled the expansion of the District through the mid-twentieth century. According to various estimates, it was once responsible for manufacturing between 70 and 95% of all clothing sold in the US.

Since that peak, it has suffered the same challenges from globalization as the American industry it once led – a more recent estimate of its contribution to domestic clothing production stands at 3%. But, even in this era of Kickstarter-ed brands, it still plays an important role in launching and sustaining new brands – as it once famously did for Ralph Lauren.

Two things led me to New York City’s Garment District (Garment District, for short), and to this piece. The first was Outlier (a brand I’ve mentioned before) – whose founders have talked publicly about how it enabled them to get their brand started. The other was the story of Hasta Sporting, a new brand I discovered last year that has chosen to move their manufacturing to the Garment District after an initial start with overseas factories.

Fig. 2 – An Outlier layer – Made in NYC (via The Hand & Eye).

Outlier formed in 2008, when a barista introduced its founders, Tyler Clemens and Abe Burmeister, to one another. While their partnership’s genesis is charmingly old-fashioned, they’re well-known for the use of innovative performance textiles and their iterative approach to product development. This reflects their goal of designing apparel that is enabling – allowing its wearers to switch between activities and social contexts that would normally require a change in clothes. Within the industry, they’ve also been recognized for being early adopters of US-based production and selling exclusively direct to consumer.

When they first met, Burmeister and Clemens had each been experimenting with making clothing that could accommodate the physical demands of a bike commute while also being suitable for office wear – their initial use case, as it were. They decided to produce a pair of pants as the first Outlier piece, and leveraged the Garment District to make their ideas into reality. As Burmeister explains, “We’re children of the Garment District. Everything we learned about making clothes was just [through] running around the Garment District asking questions.”

So what led them to the Garment District? “It was there,” Burmeister says with a chuckle. “We’re in New York and it was there. I went to the Button Kiosk on 39th Street and 7th Avenue – I just walked up to it and said ‘I want to make pants, how do I make them?’ And they were like, ‘here’s a printout, here’s a bunch of factories.’” That led to what Burmeister calls a starter factory,

“They were great for going in and learning and being scrappy. Anybody can walk in without any experience – you just have to be willing to knock on some doors and make a few phone calls, but [that’s all it takes to make things] in the Garment District. You can start for very, very little.”

Fig. 3 – The Button Kiosk in the Garment District (via 6sqft)

For Outlier, a chief benefit of the Garment District is its proximity – their offices are in Brooklyn, just a half hour away by subway. I asked what kind of advantages that provides to a company that works the way Outlier does. “It’s essential,” Burmeister responds,

“We couldn’t do a lot of what we’re doing without it. We’re prototyping, we’re releasing every week. Every day, there’s [our] people in the Garment District – managing production, fitting garments, making new samples and stuff for us to test. Right now we’re not using an in-house sample maker – so in terms of getting proper samples made, we’ve got them going in and out of the Garment District every day. So this is about as far away as we’d want to be.”

For context, I wanted to understand how many prototypes it takes to get something right – “On average it probably takes three or four; something really complicated might take five or six. A lot of times we’re building off of an existing product, so those iterations might be two off the existing design.” Creating and testing that many samples in a production lifecycle is an unusual approach within the apparel industry, and one that is enabled by being so close by to the factories they use.

As Outlier has grown, it’s faced some growing pains too: “There are factories that are so small they can only make up to fifty or a hundred units at a time. If you want a hundred and fifty, they’ll say ‘we can’t do it – go down the street, there’s a bigger factory over there.’” Or there could be other reasons to move on – Burmeister cites a need to have a different level of quality or a “different attitude towards timelines” as examples. Regardless, the process of growing up as a brand sounds not unlike growing up as a person: “It’s emotional, man. These are the people that taught us and have made stuff [with us] – we have human relationships with them.”

Fig. 4 – A shirt factory in Portugal (via Jones of Boerum Hill)

Continued growth has led Outlier to look elsewhere for the scale necessary to keep up with demand. For instance, a lot of their button-down shirt production has moved to Portugal. “If we’re doing a hundred shirts in New York, we can make a really high quality shirt at that scale, but if you want to make three hundred it’s really hard…. In Portugal right now, it’s kind of like the sweet spot that we’ve seen – it’s Western Europe, people are treated well, the pay is good and the quality is really good.”

That’s not to say they haven’t given up on finding a US-based solution, but it’s proven to be challenging to find one that suits their needs. “There are good shirt factories in America, but our shirt pattern is pretty different with the pivot sleeve. And the shirt factories that do volume well in America are very, very conservative. We’ve gotten them to do it at times and it’s just not in their DNA.”

That underscores Outlier’s commitment to making the best possible product and it still makes “a very significant chunk” of its overall production in the Garment District, where New York City is trying to invest in innovation to keep pace with competition. Regardless of the Garment’s District’s future – with Outlier’s experimental, iterative approach, it’s hard not to think that it has become encoded into their DNA, no matter where their production is based.

————————————

(via Hypoxia Outfitters)

While Outlier’s journey has been rooted in and informed by the Garment District from the start, others have found it beneficial to bring their offshore manufacturing to New York. I ran across one such company, Hasta Sporting, at the Liberty Fairs tradeshow in 2016. They were showing their Spring / Summer 2017 line and I was really struck by their use of innovative fabrics. It’s rare that you see smaller brands working with something as cutting edge as Schoeller C-Change – a breathable, waterproof membrane that opens its “pores” in response to the heat and moisture your body generates, relative to the outside weather. And rarer still to see those fabrics used in styles that owe as much to streetwear as performance outdoor apparel.

That combination gets to the heart of what Hasta’s about – as founder Tyler Rowe tells it, “I wanted to start a brand that played into the essentialist mentality of spearfishing, taking performance fabrics – fabrics with a narrative – to update traditional silhouettes to make them our own.” Design elements that play a part in what he calls their “aconventional streetwear” approach have been incorporated from such disparate sources as coach’s jackets, motorcycle jackets, Patagonia’s Snap-T fleece pullover, and the ubiquitous MA-1 bomber jacket – embellished by BDU-inspired pockets..

Fig. 5 – Hasta Sporting Bomber Jacket, F/W 2016 collection (via Hasta Sporting)

Rowe describes what it’s like to tell the story of a performance fabric like C-Change: “I don’t think it immediately sinks in… [People] need to experience it and be told about it. I think that’s when the price comes in – how do we, as a small brand, offer it at a price that’s going to be accessible enough to sell it to somebody where they’re going to be able to get it on, take it out and have that experience?”

Hasta Sporting was founded in January 2015 (“we’re still super, super young,” Rowe notes) and their early experiences with overseas manufacturing highlights some of the challenges a smaller brand can face,

“We started off in Italy and Pakistan, and then we worked with a Japanese factory in China that was letting us do smaller minimums. All of our initial relationships were predicated on these smaller minimums – [but] then as a by-product, we found that we were being pushed to the side of these larger factories. Then, from that, just came a lot of missed delivery dates – and our relationships with our retailers are so important. If we can’t deliver to them when we say we’re going to deliver to them, it really puts a strong external pressure on our relationships. And we had to bring it back to the States.”

Fig. 6 – Built for efficiency: inside a large factory in Vietnam (Reuters / Kham, via Quartz)

Rowe clarifies further: “We needed to go to a factory where we could do fifteen to thirty piece minimums on some of our pieces. The factories in New York have really given us that opportunity.” The smaller minimums help with what’s called “inventory risk,” which is what brands have to deal with when they have unsold pieces at the end of the season for which it was made. Arguably, it’s the main reason for the end of season sales we often look forward to. It can be a huge financial headwind for brands, because every dollar tied up in unsold inventory is a dollar that can’t be invested into future collections.

The move to New York has also made a huge difference in Hasta’s being able to operate more quickly. Rowe estimates the time to deliver a sample from a factory in Italy at three to four weeks. Bear in mind, there are different kinds of samples for different steps of production (“sew by” samples used to cost out factory contracts, salesman samples to show at trade shows, production samples of what the final run will look like, etc).

So imagine each sample taking weeks to produce and get shipped back to the US for approval or further modifications (which then go back into an updated sample for re-review and approval) – all before production for the final run of that piece starts. By contrast, Rowe describes what that process looks like in the Garment District: “I’m going to jump on my bike, go up today [a Friday], approve a sample, make some changes to it for our Fall / Winter ’17 development, and it’s going to be in motion Monday morning and done Wednesday.” It’s a more conventional production process, accelerated.

“Don’t get me wrong, there are fantastic factories overseas who are phenomenal craftsmen and really great at their trade, but for us as a brand right now, I think New York offers more value.”

Fig. 7 – Parka (in packable Japanese nylon), from the Hasta Sporting S/S 2017 Collection (via Hasta Sporting)

Beyond compressing a process that can take months into something that can be measured in days, there are other benefits. When producing pieces overseas,

“You’re paying tremendous shipping costs and the tax that you’re paying to get things in and out of the States is crazy. It directly affects your pricing matrix and we’re already facing an uphill battle with the fabrics we want to use in regards to pricing to get it to the customer. It’s something that’s a little bit more accessible. Doing this in the States is actually less expensive for us and lets us be a little bit more aggressive pricing-wise, which is really great.”

Rowe also describes the opportunity for a collaborative approach in the Garment District.

“I can’t thank Bree and Wilson from NYC Factory enough and then Ida and Duncan from Caroda. All of them have been so kind and helpful, and offered so much insight for me personally… this is a craft and you don’t learn a craft overnight. You very much need people to take you underneath their wing and expose you to what they’ve learned over many, many years – otherwise you’re going to continuously learn the hard way.”

Listening to [our Garment District factories], they’ve added so much because of that – just in offering little insights here and there.” This is a point that Burmeister also makes – “Everything we learned about construction – putting stuff together – we learned there [in the Garment District].”

Fig. 8 – Inside the Garment District (photo by Richard Beaven for Zady)

It’s kind of a cool note – New York City never struck me as the kind of place where you could walk in somewhere without any expertise and hope people would take you under their wing and nurture you. It seems downright old-fashioned, which is fitting, I suppose for the Garment District. And it does sometimes feels like a small town, where people look out from one another. As Burmeister recalls,

“When I first started, I would walk in [to a factory] and say ‘I want to make pants,’ and somebody would say ‘well, we don’t really do pants – we do shirts. But my friend over here – go to the fifth floor over there and talk to them.’ And then that person will say ‘we’re too busy now, but my friend two blocks away, I think she needs some work right now.'”

For all its storied history and time-honored ways of operating, the Garment District serves as a modern-day incubator of sorts – offering smaller brands a low barrier to entry, quality craftsmanship, flexibility and mentorship. It seems almost perfect for this moment in time – you can start a brand with little capital, sell online to reduce overhead costs, and take advantage of decades of expertise and experience while retaining full equity – all within one square mile in the center of Manhattan.

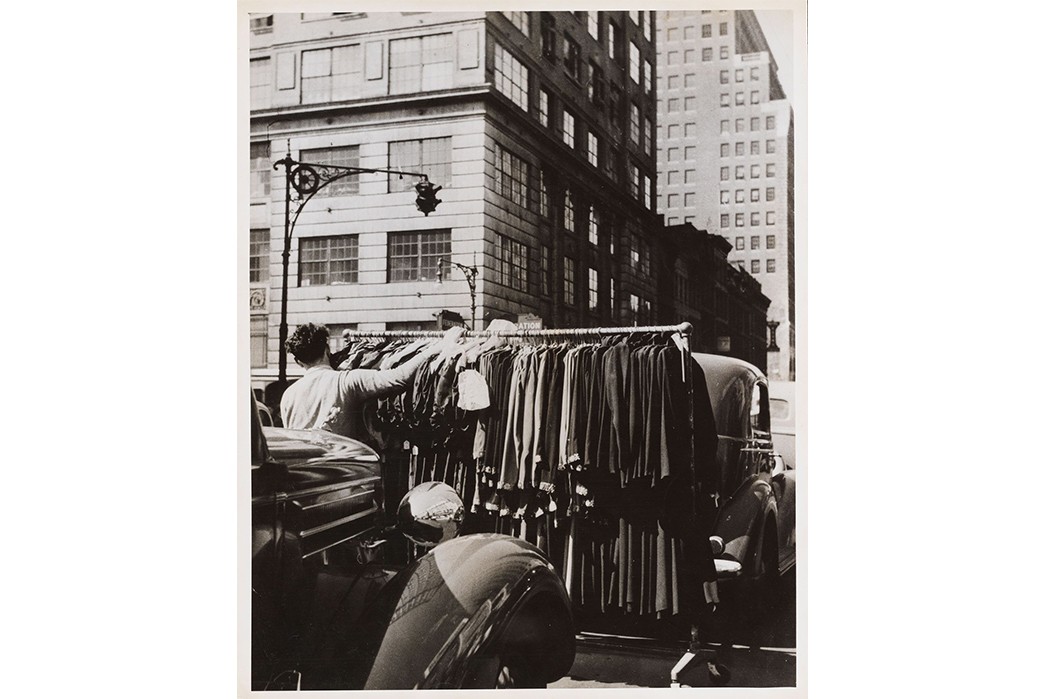

Fig. 8 – The Garment District in 1944 (photo by the US Office of War Information from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. Image via Bloomberg News)

Since I started working on this piece, the current Garment District’s future has become endangered by a more local, classically New York challenge – the rising cost of rent. Following the development of new commercial properties for garment manufacturing along the waterfront of Sunset Park in Brooklyn, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has recently proposed significant changes to the Garment District’s zoning laws.

One of its provisions includes the removal of a thirty-year old requirement that helps keep manufacturing rents affordable in a highly desirable commercial real estate neighborhood. The economics of New York City has seldom been sentimental where real estate is concerned, but I’m hopeful for an outcome that will preserve the unique value of the District.