Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

I’m standing on a train platform in San Francisco — it’s February and I’m heading to Noe Valley, in a part of the neighborhood served only by bus. According to the Transit app, it’s twenty minutes away and to get started, I just need to look for a particular train and hop on. About five trains stop and go, each one with a different destination than the one I’m keeping my eye out for; each one contributing to a growing sense of unease. I finally look at a map posted on the platform, about fifteen minutes into my trip. I check the app again for the station I’m heading to, and put my phone away. Looking back at the map, I now see there are at least three lines that can take me that far — each train has come and gone. The next one comes and I’m on my way.

It’s hard to describe the disorientation I felt that day. I knew where I was going and how to get there in a virtual sense, but it was like I was in a parallel dimension to the one I wanted to be in, with an invisible wall between the two — the Upside Down, as it were.

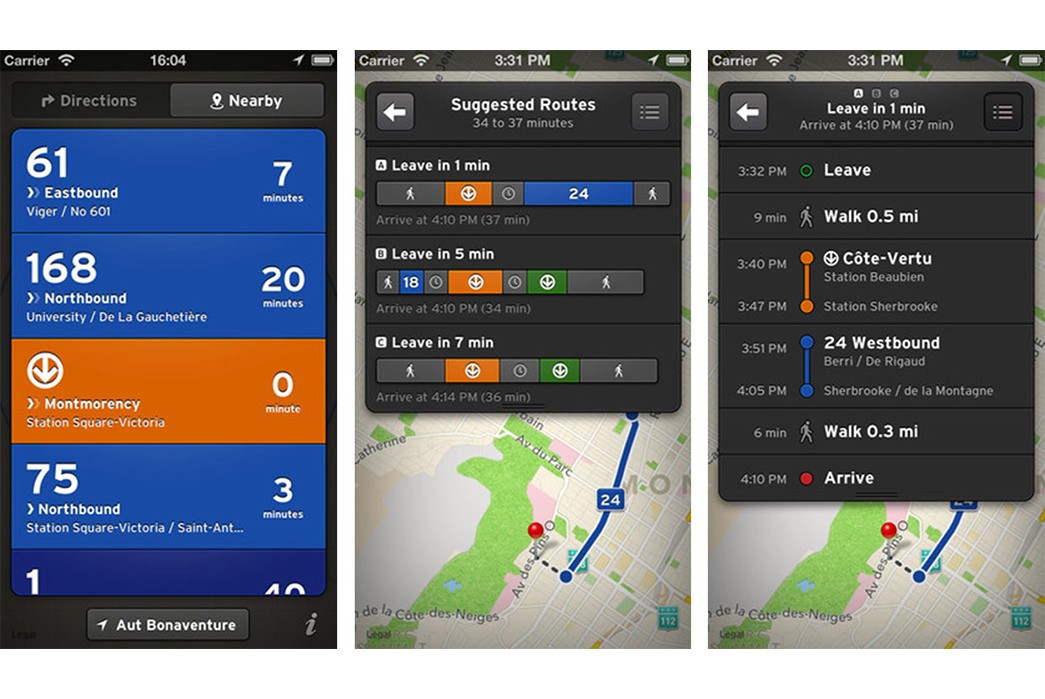

If this sounds like I’m blaming the app, I’m not. It’s a great planning tool and has worked well for me before. You plug in your destination and several public transport routes show up. Once you commit to a route, a blue dot will show where you are on your journey (so you can, say, signal your bus to let you off). Have you ever tried to use a bus map and schedule chart to get around a city you barely know? Exactly.

Fig. 2 – Transit in action. Via iMore

I’ll admit, my directional sense has never been the best, and my cognitive skills are on a long, slow decline. Believing that an app alone could substitute for being able to know how to find my way around was where it all went wrong. Looking back, my faith in technology alone to solve a problem was probably misplaced and, as I’ve learned, this may be just the tip of a digital iceberg.

Part One

This increasing reliance on digital technology — transforming the way we experience reality — is the basis for Damon Krukowski’s thought-provoking new book, The New Analog. We probably all understand intuitively that we’ve both gained and lost something from the transition, and Krukowski dives deep into those costs. His assessment of our new relationship to technology also perfectly explains how I managed to get completely lost, all while having one-touch access to every public transit schedule in the area and having GPS pinpoint exactly where I was.

You might know Krukowski as a musician (he records with Naomi Yang as Damon & Naomi and was also in a band called Galaxie 500), a publisher (Exact Change Press), or a writer (two books of poetry and the occasional freelance critique, most famously for Pitchfork). His perspective is partially rooted in a sound engineer’s understanding of recorded music, which separates what we experience into signal (the thing we’re listening for, like a vocal or guitar hook) and noise (everything else we hear that’s not intended as signal, like tape hiss or the surface noise from a poorly kept vinyl record).

And extends this paradigm to other sound contexts, like the background noise in a phone conversation, say. Ultimately, he uses it as a metaphor for how digital technology organizes our lives. It’s a binary construct for our digital age, which divides the world into ones or zeroes.

Krukowski argues that digital technology’s advancements are based on emphasizing signal at the expense of noise. And these advancements are accompanied by a corresponding collateral loss. One example he cites is music streaming services: they give us access to millions of songs, but most use audio formats that sound worse than CDs. What’s gained in convenience is offset by a degradation in quality (and the social costs are a topic for another discussion entirely).

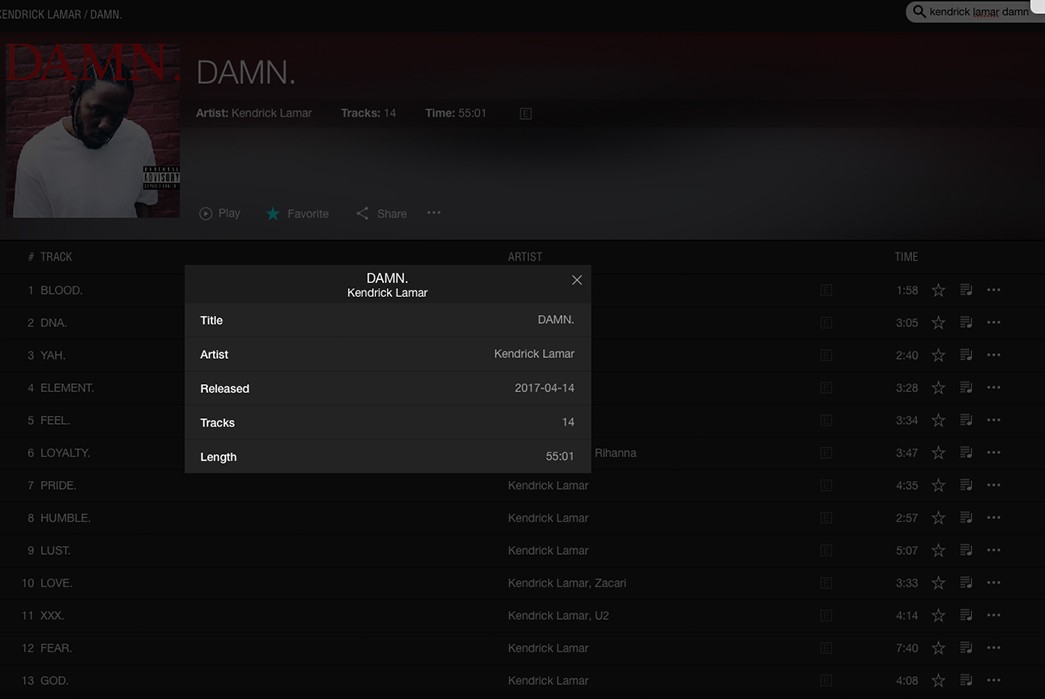

Fig. 3 – All the information on Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. on Tidal (can fit in a tweet)

Not all music streaming services operate this way (and I’m not even going to get into CD vs. vinyl), but, as Krukowski observes, even the services that offer “CD quality” resolution don’t offer more than a token representation of the information that was once packed onto albums. You’ll see a thumbnail of the artwork, but very little recording information — who played on it, or how it was made for instance, much less any critical content.

All of this, he reminds the reader, used to be standard fare for liner notes. As an example, I’m looking at Tidal right now and Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. includes only the following information about the album: artist, release date, number of tracks, and length. Mac DeMarco’s 2 adds credits (half of which are DeMarco) alongside a press blurb.

I’m sure Tidal would argue that this is up to the “content providers.” Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo debuted on the service, and includes a litany of credits comparable to the credit “crawl” at the end of a special effects-heavy Hollywood blockbuster. But let’s be honest, how many of you know how to find this information on your streaming platform, let alone consult it on a regular basis? If you do and desire more, there’s a service from Roon Labs that purports to re-add this context to your digital listening — along with other ways to help manage and play your digital media — for a modest monthly fee.

All of this ancillary information that once accompanied the music is what Krukowski calls noise. It’s considered to be secondary, but when you lose it, you lose critical pieces of contextual information that help enrich your listening experience. As he puts it, in what amounts to a text-based stage whisper, “noise is as communicative as signal.”

In a very real way, it’s my inadvertent disregard for the “noise” of my surroundings that led to my disorientation beneath the streets of San Francisco. In focusing on the app, I completely blinded myself to the basics of navigation — to use a map, you need a compass to orient yourself to the map. And, as I found, a blue dot in a smartphone app does not a compass make.

Part Two

That incident was embarrassing at the time, no doubt. There was a woman who attempted to help me out, while maintaining an overall sense of wariness about what could possibly be wrong with me. (Perhaps, if I had been holding a tourist guidebook with an expensive camera around my neck, that would have aided her understanding). And the more I thought about it, it’s also reflective of some bigger trends in our society. Krukowski writes about the blue dot: “…the subject is fixed at the center point of a field in motion. The resultant perspective is literally, dizzyingly self-centered.” It’s a persistent “you are here” marker around which the world magically revolves.

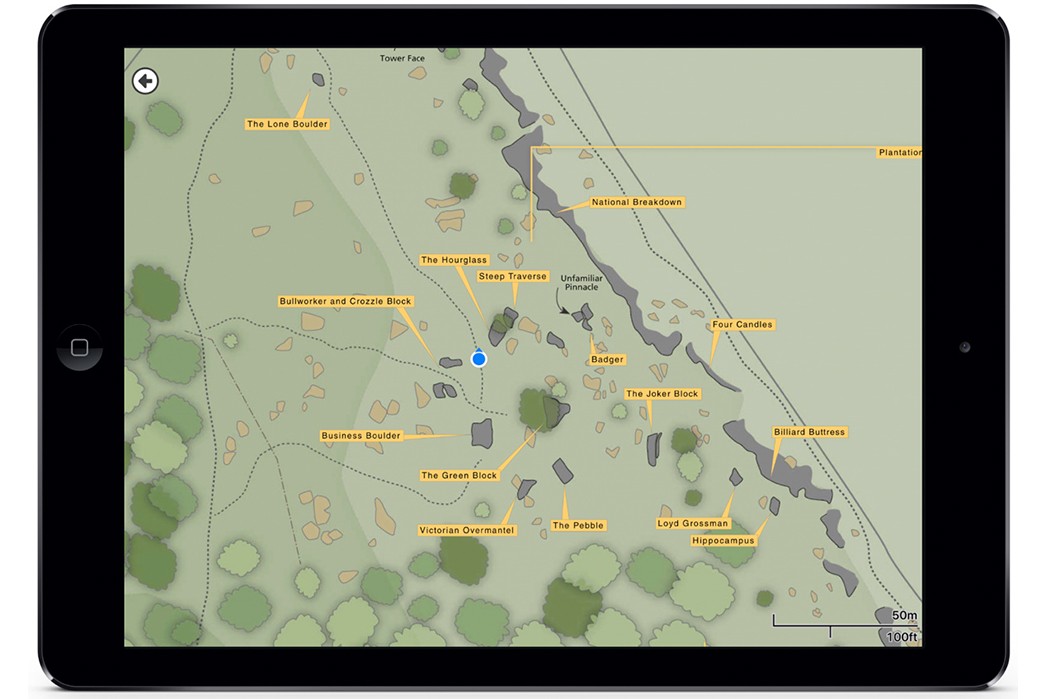

Fig. 4 – Navigation app for rock climbing. I’m guessing it functions best when oriented within the physical world using the landmarks as reference. (via Rockfax)

The dilemma starts here. As we increasingly rely on our phones to mediate our real-world lives, the software’s creators are eager to pitch us things based on what they think we want. This creates a feedback loop that emphasizes the things to which we respond favorably. And the algorithms of Facebook, Google et. al. place primacy on things that reinforce our preferences, while those that may not align as neatly fall under a rising tide of digital chunder.

Pretty soon, our feeds can be overwhelmed by the thoughts and beliefs that reflect our own. The danger is twofold: first of all, we may forget that reasonable people can hold different opinions than ours. And based on that, we may come to the wrong conclusion that anyone who doesn’t agree with our opinion is unreasonable. Secondly, without actual context, we can be prone to reading others’ social media updates outside of their intended meaning, overreacting swiftly.

As an example, I think of a former teacher I consider to be a friend, who has (and always has had) political views very different than my own. It’s never been a problem when talking in person — we’re respectful of each others’ ideas and maintain a sense of civility by acknowledging both viewpoints in our discussions. Simply put, we see each other. I recently became friends with him on Facebook and was dismayed at some of the things he would post, seemingly unchained from civil norms. Nothing hateful or personal, just strongly worded political thoughts. Still, it felt revelatory — like overhearing friends talk about you when they think you’re out of earshot.

I had to remind myself of our past interactions, in order to not read the worst into what he shared. And I have to think that he, in his mind, is addressing these posts to a certain audience, without thinking of the others in his online community that might not receive them in the same light. On platforms that aim to provide interconnectedness, we are at risk of entering into our own echo chambers.

Krukowski describes this phenomenon: “We occupy the space simultaneously, but not together.” He was talking about a hypothetical subway car full of passengers engrossed on their phones, but he could just as well be describing the interconnected virtual space they were each, individually, experiencing. Each of our online world’s reflecting our own worldview back at at us, each of us alone together.

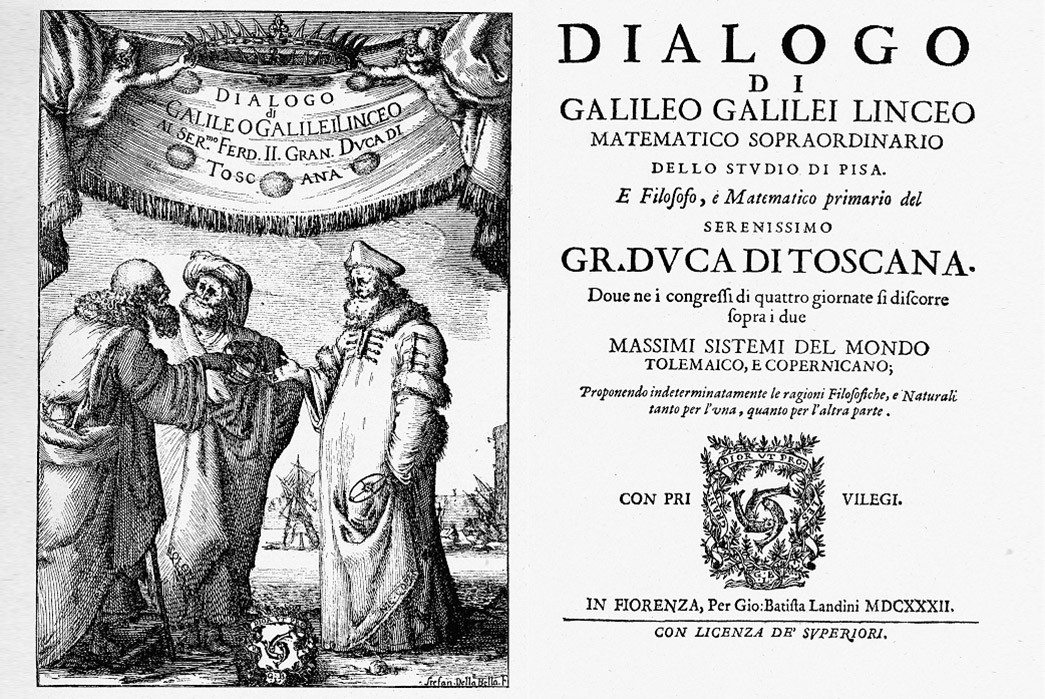

The hazard of the blinking blue dot at the center of the map is that you’re always there, and the world around you is seemingly recalibrating itself to your wishes. It’s a return to the value system that found Galileo guilty of heresy for arguing that, literally, the universe doesn’t revolve around us.

Fig. 5 – Frontispiece (by Stefan Della Bella) and title page of Galileo Galilei’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published by Giovanni Battista Landini in 1632 in Florence. In this Dialogue, Galileo defended the theory of heliocentrism (Image obtained from Wikipedia from the collection of the Museo Galileo).

And it doesn’t. I worry sometimes that we lose sense that the account names and avatars we interact with online (mostly) correspond with real human people. Lives are noisy affairs, and their details are easy to lose track of, shorn of context on a social media feed. Empathy is a great bridge between people, but it requires us to recognize others as relatable.

There’s a great quotation from Kevin Durant — it originally aired on Bill Simmon’s cancelled HBO show, Any Given Wednesday — that is, perhaps, one of my favorite things a professional athlete has ever said. It was about his decision to leave Oklahoma City for the Golden State Warriors:

“Nobody cares about what I want as a person. It’s all about what I can do on the basketball court. They don’t care if I like going fishing on Tuesdays or like taking pictures on the street. Nobody cares as long as I can shoot that ball into the hoop. Why should I care what they think if they don’t really care about me as a whole?”

Durant’s choice was questioned by many, but his comment helps us reframe it through his eyes. These potentially rhetorical, objectively incidental details of his life help us understand that it was, in the end, a personal decision. And it emphasizes the reciprocity involved in even the most basic and remote human relationships.

And what to do about all of this? Krukowski offers, as a solution: “Just as the disorientation from GPS navigation is solved by paying attention to the analog clues of location all around, the isolation of signal in the digital environment can be corrected by a simple reawakening to the work accomplished by noise.”

He puts it succinctly, and with emphasis: “Noise has value.” Living a noise-enriched life requires effort, and cost. It’s why we travel, have lunch with an old friend, go to stores we love to buy actual things. And it’s why we should always read signs when traveling.

Epilogue

If you’d like to buy this book, its author has noted that IndieBound can help you find an independent bookseller near you that carries it.

The New Analog: Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World, by Damon Krukowski, The New Press, 224 pages, $24.95