Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

There are few founding fathers that still have the resonance of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (perhaps better known as Mahatma Gandhi). As with many political leaders, he led a complicated life–its nuances are best left to other writers, in other places. That said, I’m pretty sure the endurance of his appeal has to do with the universal optimism of his message, that through individual, non-violent choices, we can collectively make the world a better place. While most of you are familiar with his theories of non-violent resistance, his cause also had a distinct emblem, a woven fabric called khadi.

If you see any picture of Gandhi from his 40s on, chances are he is dressed in khadi. It’s a woven fabric, usually from cotton but also blended with other natural fibers, such as silk or wool. The key aspect is that its yarns are spun by hand by a spinning wheel called the charkha, which imparts a pleasantly uneven feel. It’s not quite slubby but certainly in the ballpark.

The fabric is breathable when hot, and surprisingly insulating when cooler (at least compared to, say, linen). And its hand-spun nature means its yarns are easy to produce at a nominal cost but unlikely candidates for mass production–two characteristics that are crucial to understanding how it came to symbolize Indian independence.

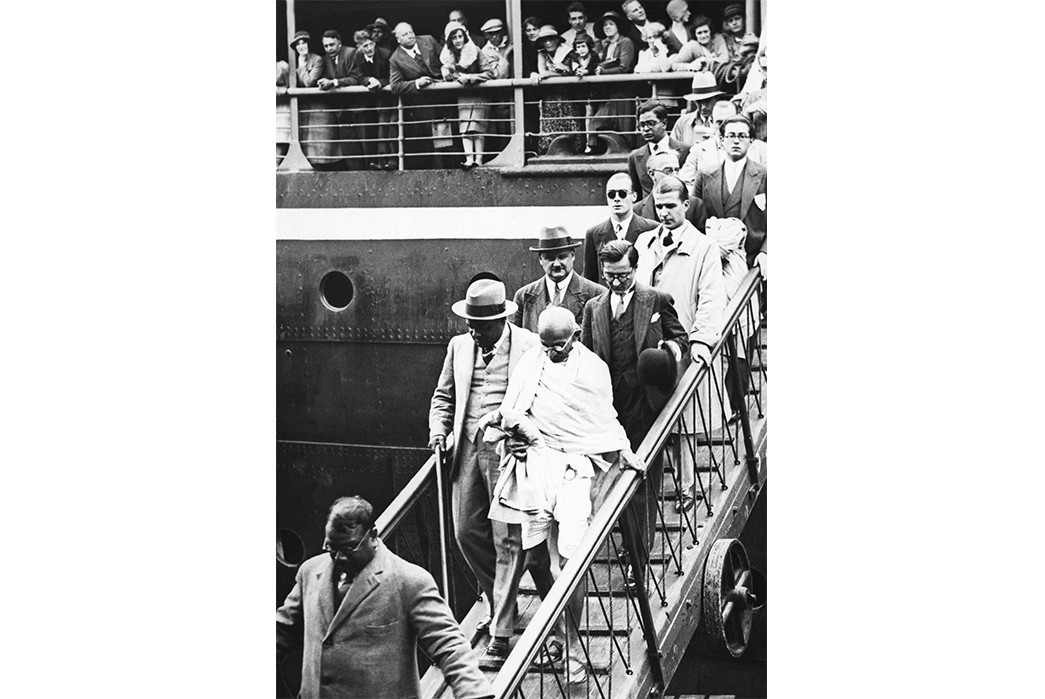

Fig. 2 – Gandhi’s Visit to Europe (early 1930s). Uncredited photo via Pinterest.

Spinning khadi was an obscure craft by the time the movement for Indian independence gained momentum in the early twentieth century. As a British colony, India’s natural resources weren’t really its own. Its cotton was being harvested and taken to England for processing, and the resulting garments and fabric were imported back to India at substantial markup, which was a boon for British industry. As I’ve written about before, this system deprived India of the opportunity to develop local industry. Opposition to this exploitation gave rise to an Indian movement called Swadeshi (self-reliance), a form of economic protest that favored the consumption of Indian products as opposed to British imports. Khadi, made from Indian cotton using traditional technologies, was a perfect fit for this movement.

Gandhi himself embraced khadi at an ashram he built on the banks of the Sabarmati River, near Ahmedabad. It was the perfect way to combat colonial industrialization while lifting Indians out of poverty. The biographer Robert Payne describes:

“Perhaps his sudden interest in the spinning wheel arose from the proximity of Ahmedabad, one of the largest textile centers in all India. He knew nothing about spinning, and had some trouble finding a simple portable wheel and someone to show him how to use it. Finally, toward the end of 1917, a widow, Gangabehn Majmundar, possessing means of her own and accustomed to riding from one village to another on horseback, found an ancient wheel in a lumber room in Vijapur in Baroda. It was dusted off and presented to Gandhi […] the first spinning wheel was set up in Gandhi’s study, the humming of the wheel serving as the background music of his thoughts.

“The khadi (homespun) movement had begun. In time, there would be hundreds and thousands of spinning wheels, but the beginnings were slow. The original wheel was carefully studied, taken apart, adapted and simplified so that it could be used by untutored peasants, and all this was done in the shadow of the Ahmedabad mills (Payne, 321).”

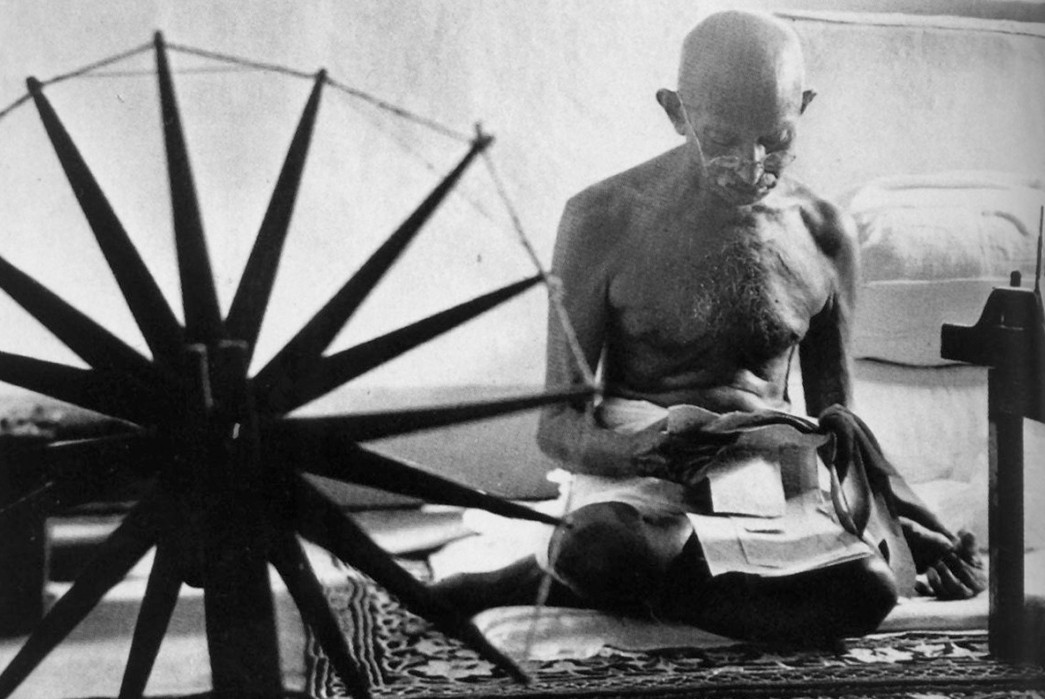

Fig. 3 – Gandhi at his charkha, 1946 (photo by Margaret Bourke-White)

Not that those mills stood to gain from this movement. Even as Gandhi encouraged the Swadeshi movement’s public burning of foreign cloth, he “urged the people not to substitute it with Indian mill products; they must learn to spin and weave themselves (Chadha, 254).” Gandhi practiced what he preached, and there are accounts of his personal quota of spinning two hundred yards of yarn per day (Shirer, 51). He traveled with a spinning wheel, taking it with him for his landmark trip to Europe in the 1930s (Shirer, 158). Beyond its intent to revive domestic production and thwart British imports, khadi became a uniform for Gandhi’s followers, who “wore caps, shirts and dhotis of homespun cloth.” (Payne, 321)

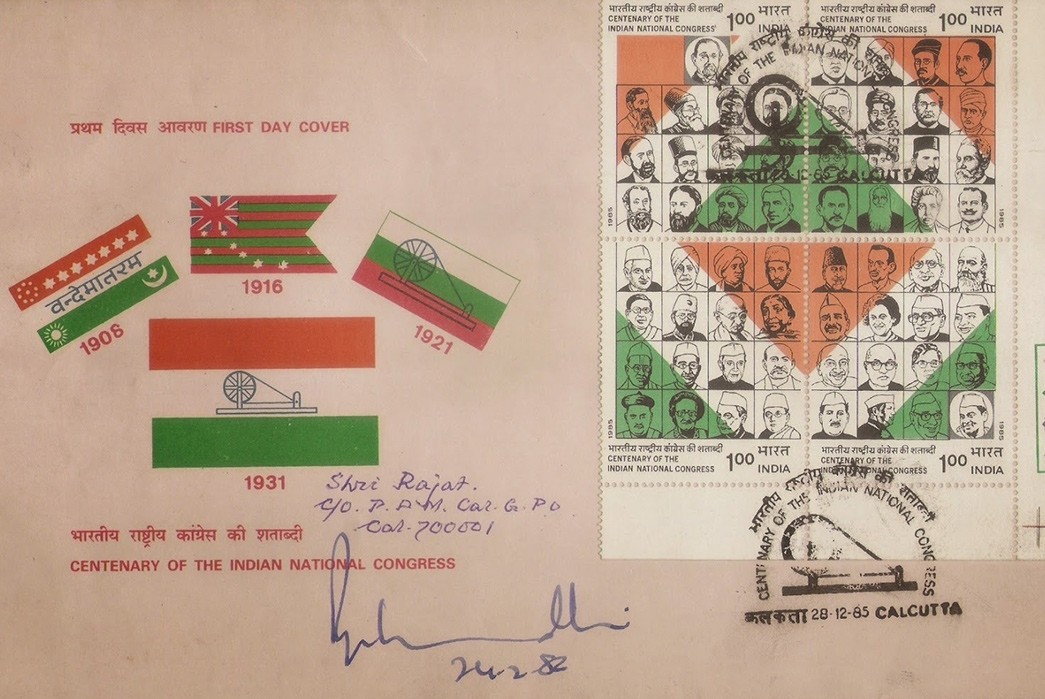

And it soon became a symbol for the cause of Indian independence. In 1921, Congress (Gandhi’s political party, the first for a unified India) adopted a flag portraying a charkha (and made of khadi, of course). And in 1924, Gandhi presented a resolution to the executive committee of the Congress party to mandate that his party’s members spin at least a half hour a day and send in the results of these efforts on a monthly basis. By 1926, an All-India Spinners’ Association, established under Congressional authority, numbered about 50,000.

Fig. 4 – The evolution of the Indian flag, which portrayed a charkha from 1921-1947 (via flagstamps.blogspot.com)

For all the power of its message, by the mid-30s, Gandhi realized that khadi would not be enough:

“Spinning and weaving would retain their place, but they needed to be supplemented by a whole array of traditional crafts that were losing out in competition with processed and manufactured goods being produced more cheaply in city factories and workshops. Villages had once known how to turn out their own handmade pens, ink, and paper; they ground their grains into flour, pressed vegetables for their oils, boiled unrefined sugar, tanned hides into leather, raised bees, harvested honey, ginned cotton by hand. For their own salvation, they needed to do so again, Gandhi taught; and it was a national need to support them not only by wearing homespun khadi but by consciously giving all they produced a preference over manufactured articles, to undo as far as possible the ravages of the Industrial Revolution.” (Levyveld, 260)

While Gandhi’s dream for Indian independence was realized in 1947, his hopes for lifting India out of poverty through khadi and other village production never materialized. Nevertheless, its legacy still lives on under the leadership of the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (established in 1956). By law, the Indian flag must be made of khadi, and the right to its manufacture is allocated by the Commission.

Fig. 5 – Khadi shirt (note tonal variation)

I came across khadi during a business trip to Hyderabad – my work schedule prohibited an exploration of the city, but there was a crafts market (called Shilparamam) near our office. My hosts explained to me the history of the fabric, and I ended up getting a shirt (for me) and a dress (for my wife). True to the regional nature of khadi, they were of the pure cotton variety. The shirt ended up with a subtle tonal colorblock (due to yarn dye variation) and became a summertime favorite.

My sense was very much that this was the standard distribution channel for clothing made from the textile, although it seems this may be changing. For instance, Levi’s produced a limited capsule line of khadi jeans, jacket, and shirt in 2014 (which I would love to check out, but sadly was limited to sale in India). Each piece in the collection apparently includes a tag with the name of the weaver and the place of its cloth’s origin. More recently, an entrepreneur named Siddharth Mohan Nair launched a self-described”Swadeshi brand” called DesiTude, which features a small collection of khadi denim pieces, including jeans and jackets. And the famed yoga guru Baba Ramdev has also announced his intent to produce “Swadeshi jeans” in the spirit of the political movement that gave birth to the country.

Fig. 6 – Levi’s khadi trucker jacket and natural-colored jeans (via Myntra)

Khadi production still yields a tricky supply chain, as Suniti Ila Rao describes – and scaling the production of khadi garments faces the same headwinds as it did during colonial times, namely its time-consuming method of production and competition from imported fabric technologies. As Rao noted in 2014,

“India’s denim production is expected to grow to 1 billion meters per annum by 2015, yet there is nothing Indian about it: the technology is imported and designs are from Italian and American makers. Khadi, on the other hand, is India’s legacy and luxury – naturally washed, chemically unprocessed, hand-spun in much lower quantities – only 91 million square meters per annum in 2012-13.”

It also retains its historical associations – which is exciting to at least one foreign writer, but it may have retained enough of that to feel dated, in the same way that the smell of patchouli may bring back memories of a bygone hippie era to younger Americans.

Khadi has made some inroads into western denim with companies like Seven Senses offering selvege khadi fabric wholesale.

Aside from all that, khadi is very much its own fabric – its porous, less structured nature means it will never read as denim unless doctored with synthetic fibers. And traditional garments may not be the best way to position it as something young people might want to wear. The spirit of Swadeshi is still alive though, and when there’s a will, there just might be a way – especially with growing interest in artisanal products and sustainability. Here’s to the hope that this fabric, so alive with meaning, may yet have a bright future ahead.

With gratitude to Vamsi Bodduluri, Shankar Lal and Navoday Mudike for their hospitality.

References

- Chadha, Yogesh. Gandhi: A Life. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997.

- Green, Martin. Gandhi: Voice of a New Age Revolution. Continuum, 1993.

- Levyveld, Joseph. Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

- Mehta, Ved. Mahatma Gandhi and His Apostles. The Viking Press, 1977.

- Payne, Robert. The Life and Death of Mahatma Gandhi. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1969.

- Shirer, William L.. Gandhi – A Memoir. Simon and Schuster, 1979.