Late last year, we received probably the worst news possible in the American denim scene; Cone Mills White Oak Plant–the last selvedge denim mill in the United States–would close permanently on December 31, 2017.

International Textile Group, Cone’s parent company, cited the reason as, “Changes in market demand have significantly reduced order volume at the facility as customers have transitioned more of their fabric sourcing outside the U.S.” Translated, people weren’t willing to pay the premium price for domestically-produced fabric and companies simply aren’t buying enough to keep the looms running.

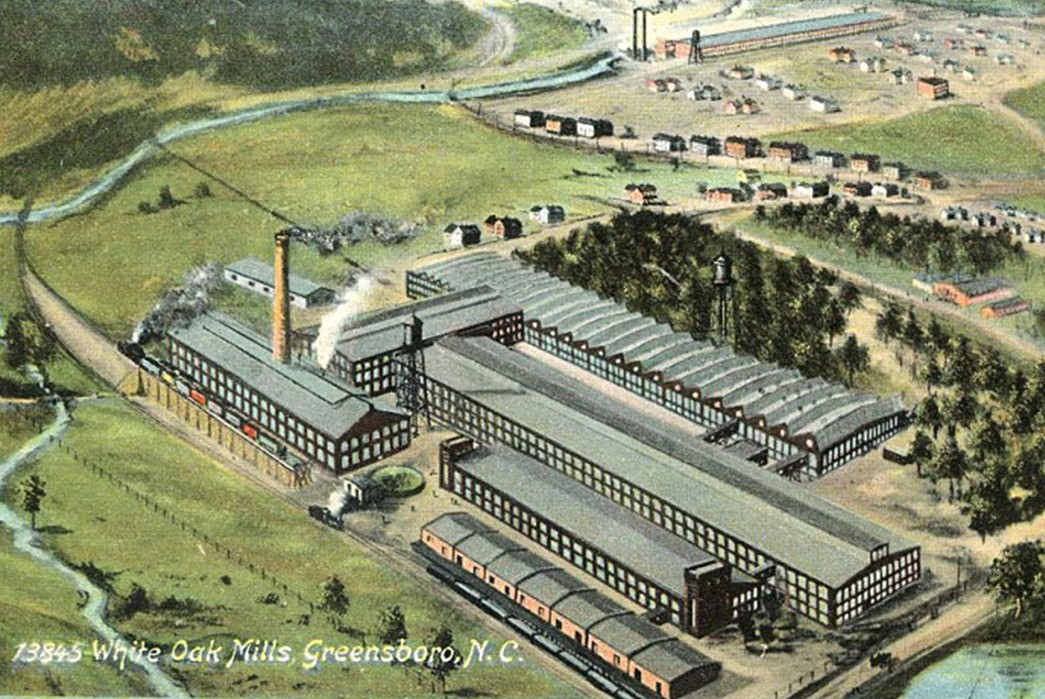

White Oak was the very last of a now extinct breed. The mill opened in Greensboro, North Carolina 112 years ago, in 1905, and has produced fabric and denim continuously to the present day. The facility was over a million square feet large and, according to Cone VP of Product Development Kara Nicholas, was at one point the largest mill in the world. White Oak was perhaps most noteworthy for the “Golden Handshake” deal struck with Levi Strauss & Co. in 1915 to be the exclusive manufacturer of the XX denim used in the brand’s 501 jeans.

The Levi’s / Cone Mills “Golden Handshake” recently commemorated in a 2015 LVC collection.

They were also often the first and last source of fabric for dozens of new brands who needed high quality denim at low minimums and needed it fast. Many of our favorite like Raleigh Denim, Roy, Railcar, Tellason, Rogue Territory, Left Field, Freenote Cloth, Norman Porter, and Levi’s Vintage Clothing relied heavily on Cone Mills White Oak as the only source of domestic selvedge denim.

And yet as Made in USA raw denim skyrocketed in popularity in the last decade, White Oak’s output seemed to wane. For every new style they introduced (natural indigo, open spun), two more seemed to disappear (duck canvas, unbleached natural, sulphur black, tweed weft). From our (albeit myopic) corner of the market, it appears that demand was at an all time high, so the question remains, why did it close?

The Untold Business History of Cone Mills

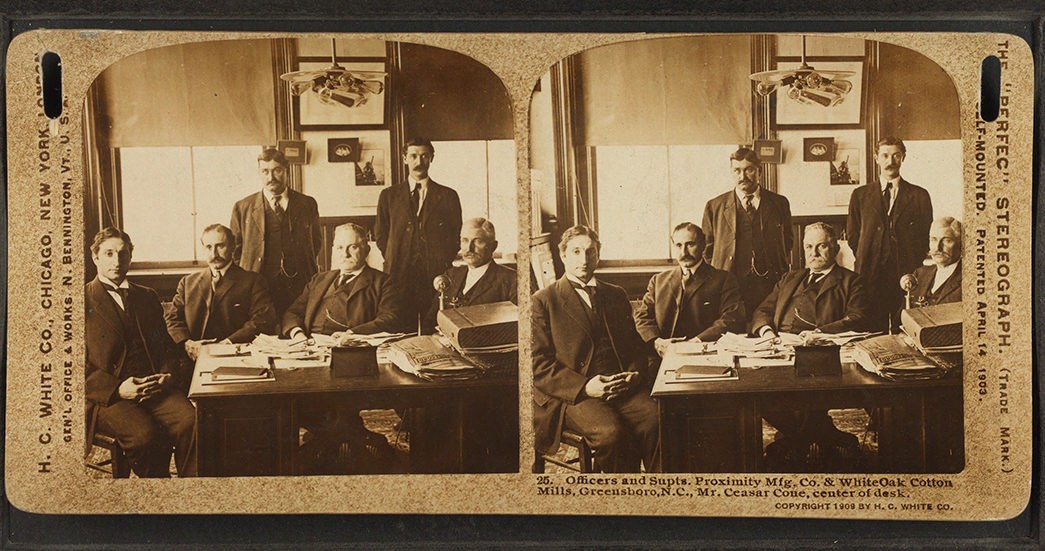

Stereoscope of Cesar Cone, center at desk. Image via Wikimedia.

The story of textiles in America is one of constant amalgamation. Over the course of Cone Mills’s 126 year history, the company has merged and acquired or been acquired countless times.

Cone Mills itself was founded by Moses and Cesar Cone, the eldest sons of a Bavarian immigrant who ran a dry goods business (sound familiar?). In the 1880s, the Cone brothers expanded their father’s grocery business into wholesaling tobacco, leather goods, and eventually cotton. The brothers were convinced that they could broaden their empire by vertically integrating and opening their own mills to produce fabric from that cotton. They believed the best place to locate such facilities was Greensboro, North Carolina, a town close to the southern source of their cotton and with the infrastructure to support a milling operation.

In 1896, the Cones opened their first facility, the Proximity Cotton Mill, which would also be the name of their new company. Caesar Cone thought that cotton denim, the sturdy American work cloth, would be in constant demand in a rapidly developing country so the indigo blue twill became the focus of their production. After their initial success, the Cones opened a second denim facility in Greensboro in 1905. The new plant was built near a large oak tree, and being men of more business than creative imagination, they named the new facility White Oak.

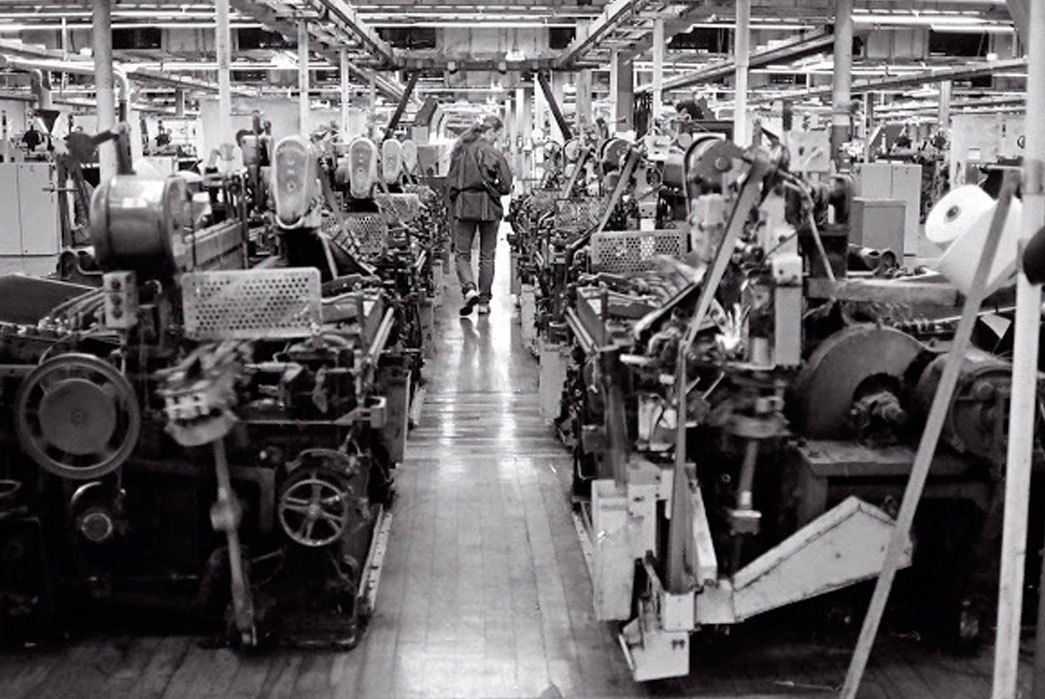

Image via WGSN.

Proximity continued to open new factories at a breakneck pace and had no less than seven facilities to its name (White Oak being just one) by the time it secured the “Golden Handshake” agreement with Levi’s in 1915 and began to produce massive quantities of fabric for World War One. Proximity was quick to diversify in the aftermath of the booming war economy so the company was not fatally damaged by the Great Depression a little over a decade later. This put them in an advantageous position as a one of the top fabric producers for the military effort in World War Two.

In 1948, company management decided a name change was in order and Proximity would henceforth be known as the Cone Mills Corporation, after the company’s founders. Cone Mills went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1951 and soon saw rapid growth as denim became accepted as American casual wear in the 50s, 60s, and 70s. Cone used these gains to diversify into a variety of related industries including spinning, bleaching, sanforization, furniture upholstery, and polyurethane cushions.

Cone Mills spinning operation in Greensboro in 2005. Image via Greensboro.

The story begins to unravel in 1983, when Cone was the target of corporate raider Western Pacific who began to buy up stock for a hostile takeover of the company. Cone repelled Western Pacific with their own leveraged buyout by borrowing a significant amount of money to buy all the outstanding stock and go private once again.

Things would not get much better. By the 1980s, the quality of foreign fabric producers (many in Japan) began to rival what was produced in the United States but significantly reduced cost. Cone campaigned that their goods were “Made Proudly in USA”, but such pleas were largely unheard and Cone closed 10 facilities between 1977 and 1990, including their first, the Proximity Cotton Mill.

NAFTA signing in 1992. Image via TPS Congress

1994 would deal a double blow. First, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect and effectively eliminated textile and apparel tariffs (among many others) between the United States, Mexico, and Canada. Over the next decade, companies like Levi’s, Lee, Wrangler, The Gap, Lucky Brand, and many others moved the majority of their production out of the United States. With fewer garments produced domestically, it became less advantageous to buy domestic fabric and more brands used fabric made closer to their production country. Second, the World Trade Organization called for an end to textile and apparel quotas worldwide by 2005. Previously, countries could set limits to the amount of fabric they wanted to import (i.e. the U.S. would only import 5 million yards of denim from China, 2 million pairs of jeans from India, etc.). In ten years, textile and apparel manufacturers would all be competing directly against each other without such regulation to artificially protect domestic mills like Cone.

Cone Mills Corporation recorded its highest annual revenue with $910 million in 1995, but that was still at a net loss of $3.3 million. By 2003, only a fraction of the clothing consumed in the United States was being produced domestically and much of what was, was being made with imported fabric. The global wholesale price of denim had dropped 27 percent in the last four years. Cone Mills had diversified into their own value operations in Mexico and China, but it was too little too late and they filed for bankruptcy.

Wilbur Ross. Image via Epoch Times.

Enter Wilbur Ross, a billionaire investor who saw opportunity in failing domestic textile producers. In March of 2004, Ross bought Cone Mills for $46 million. He also bought their longtime competitor Burlington Industries and several other smaller manufacturers and rolled them all into a new conglomerate, the International Textile Group (ITG). ITG sought to take the knowledge and name brand appeal of these domestic mills while moving their operations overseas, a tactic he employed to great success with bankrupt steel companies just two years prior.

But textiles didn’t prove to be the quick turnaround he found with steel. ITG began with a combined revenue of about $900 million in 2005 but had dropped to $610 million a decade later in 2015. The company’s flagging sales combined with Ross’s political ambitions lead him to sell ITG to private equity firm Platinum Equity in October 2016 for $99 million. Ross then became Secretary of Commerce in the Trump Administration February of 2017 (and more recently, surrogate connection to Russian shipping interests).

Platinum’s business model involves buying flagging companies and drastically reducing the bottom line until they can sell them off for a profit. With ITG, one of those line items happened to be the historical crown jewel of the Cone Mills brand, the White Oak Plant, which, for the reasons mentioned above, had become the last operating selvedge denim mill in the United States. On October 17, 2017 ITG announced it would close the White Oak Plant in Greensboro at the end of that year.

So Why Did it Close?

I was afraid something like this might happen when ITG announced the sale to Platinum last year, but Cone assured customers and fans alike that they had every intention of keeping the plant open. Members of the artisanal raw denim community were shocked to hear of White Oak’s end. Roy Slaper of Roy Denim believed the mill was doing amazing business, “I was constantly told the mill was operating at full capacity. I’m shocked they didn’t have enough orders to keep it open.”

Amy Leverton, denim trend forecaster, author of Denim Dudes (and contributor to this site) finds it hard to comprehend as well based on her past experience with White Oak, “I visited Cone denim in 2004 when I worked with Duffer St. George to create a White Oak custom selvedge…White Oak around that time was like a graveyard. The White Oak Draper room was not working at half the capacity it was when I went back to visit last year to celebrate their 125 year anniversary. The industry has grown exponentially since my visit in 2004 and developed into a still-niche but very very healthy little scene.”

Image via WGSN.

But the selvedge business was only a small part of White Oak’s output. Longtime White Oak customers Tony Patella and Pete Searson of Tellason reminisce in their blog post on the closure, “If White Oak is the size of a football field, the Draper looms that make the selvedge denim take up the space of half of an end zone. The mill depends on selling a large volume of fabric produced on their modern looms — the exact type of fabric large brands and retailers use.”

There were only about 40 operational Draper looms on the White Oak floor. That operation was made possible by the wide, non-selvedge denim the other roughly ninety percent of the mill produced. The brands that bought that kind of denim were the small- to medium-sized “Premium” brands that still produced in the United States–the likes of True Religion, 7 For All Mankind, and Citizens of Humanity. And as those brands waned in recent years, so did White Oak’s viability.

The tragedy is consumer awareness of Cone Mills White Oak selvedge denim was likely at an all time high. Can you imagine the same level of outcry over the closure of any other fabric mill in the world? But such a title is roughly equivalent to “tallest dwarf” and speaks more to how little the average consumer cares about the source of their clothes, much less the fabric of which they are composed.

White Oak was special for the same reasons that doomed it. It was a steam locomotive that somehow still serviced a commuter train route. The global apparel economy had long since moved on, but the emergence of a niche heritage scene along with a few medium sized brands still looking for domestic non-selvedge fabric kept it afloat and the tireless dedication of the people working at Cone Mills like Kara Nicholas kept it alive far longer than every other facility like it in the United States.

Even if it was no longer profitable, there was a great deal of brand value in having something so historically significant at the center of Cone’s operation. The new ownership at Platinum, however, must not have seen it as enough to keep the doors open and their track record shows no evidence of sentimentality.

The final Cone Denim product. Image via Self Edge and Roy Denim.

Many have wondered (myself included), “why doesn’t someone else just buy it and keep it running?” Unfortunately it’s not that simple. Even if Platinum were to give it over for free, the White Oak facility is over a million square feet (that’s nearly 20 football fields to continue Tellason’s analogy) and the costs of maintaining and heating would be astronomical.

It’s also surmised that much of White Oak isn’t up to current environmental code, but had been grandfathered in due to its age and continued ownership by the Cone Mills Corporation. A new owner–that didn’t also own Cone Mills entirely–would likely be responsible for all of the updates, a cost that would, again, likely be astronomical.

And finally, many of the people who worked at White Oak have been there for decades and generations. They took great pride and care in their work to the last shift. Like the mills themselves, experienced millworkers are a dying breed, and I would sympathize if they’d rather just shut it down instead of hand over control of production to someone without the background to run it properly.

It appears White Oak is closed for good.

Where Does American Denim Go From Here?

Levi’s Made in the USA 501 jeans, advertised as being made “with some of the last yards of White Oak selvedge.” Image via Unionmade.

Cone Mills White Oak was the very last industrial scale selvedge denim operation in the United States and a good number of brands relied on them for fabric: Roy, Tellason, Raleigh, Railcar, and Left Field to name a few. There are still a number of other mills elsewhere in the world producing selvedge denim, so those brands will live on even though a main source of fabric has fallen.

For new brands, though it will be much more difficult to acquire small runs of selvedge denim if they don’t have the means or scale to import it. Resources like Pacific Blue Denims and other importers will become much more critical to new American labels.

Other American denim-makers are struggling as well. The DNA Textile Group announced it would close its Denim North America production by the end of this month in November. This leaves only Mount Vernon Mills as pretty much the last large scale denim producer (selvedge or not) left in the country.

There are also other, albeit much smaller, selvedge denim operations emerging in the U.S. in the wake of the closure. Most notable is Huston Textile Co. in Sacramento, which is already producing denim on their own Draper X3 loom. It will be years, though, before anyone will be able to match White Oak’s output and price point.

Denim has and will likely always be the fabric of America. After all, is there anything more American than exporting a piece of culture so hard it’s no longer even made here?

Lead image via WGSN.