Depending on who you ask, the loafer has any number of plausible origins. These vary from Iroquois moccasins, Norwegian fishing shoes, or most likely, some combination of the two. However, the loafer, upon its arrival in the U.S. made an undeniable splash, typically among the fanciest and wealthiest contingents of society.

From murky beginnings to clear-cut commercialization, the loafer and its various cousins have come to symbolize a kind of leisure and comfort reserved for those most fortunate. In more recent years, however, its acceptance in high-end fashion has had an ironically democratizing effect, making the shoe a menswear essential and putting it on the feet of even Average Joe’s.

The Origin Stories

Teser shoe. Image via Pinterest.

The origins of the loafer are confounding and contradictory, but there is certainly a Norwegian connection. The Aurland region of Norway is often considered to be the birthplace of the modern day loafer, but these narratives largely disregard the Native American influence on the shoe that came to be considered the modern “Penny Loafer.”

Teser shoes, much like the one seen above, had been worn in Norway for a very long time. When, at the turn of the century, many Norwegians began adopting a more formal and English style of dress, some more traditional communities clung to their old ways.

One theory attributes the creation of the loafer to Wildsmith shoes of London in 1926, who had been asked to design a shoe for King George VI. This theory is plausible when one considers the frequent angling trips made by English royalty to Norway. If, as is often explained, Englishmen began occasionally wearing Teser shoes during their trips abroad and bringing them home, did Wildsmith really create the loafer, or just copy the Aurland Teser shoe?

The first Aurland shoe. Image via Pinterest.

Nils Tveranger, an Aurland native, began designing shoes at a very young age. By 1908, he had completed a shoe-making apprenticeship in the U.S. and was hard at work on the above shoe. His first edition of the Aurland shoe was a purely Norwegian creation, it had laces, a raised heel, and greatly resembled traditional regional footwear.

His second effort, was far more loafer-y. In 1920 he patented his new shoe, which featured a gathered moc-toe, low heel, and no laces. Tveranger’s loafer design would have certainly been in circulation by the time Wildsmith designed their version. Regardless of who copied who, neither of these designers would have made a loafer without Native American influence.

Making the Aurlandskoen. Image via National Library of Norway.

Tveranger, who we shall assume invented the loafer, was greatly influenced by his sojourn in the U.S., particularly by the Iroquois moccasin, with its signature gathered toe stitch. The fact that this detail was not included in any version of Aurland shoe before Tveranger’s trip to study art and history in the States is incredibly important.

The Loafer Comes to Stay

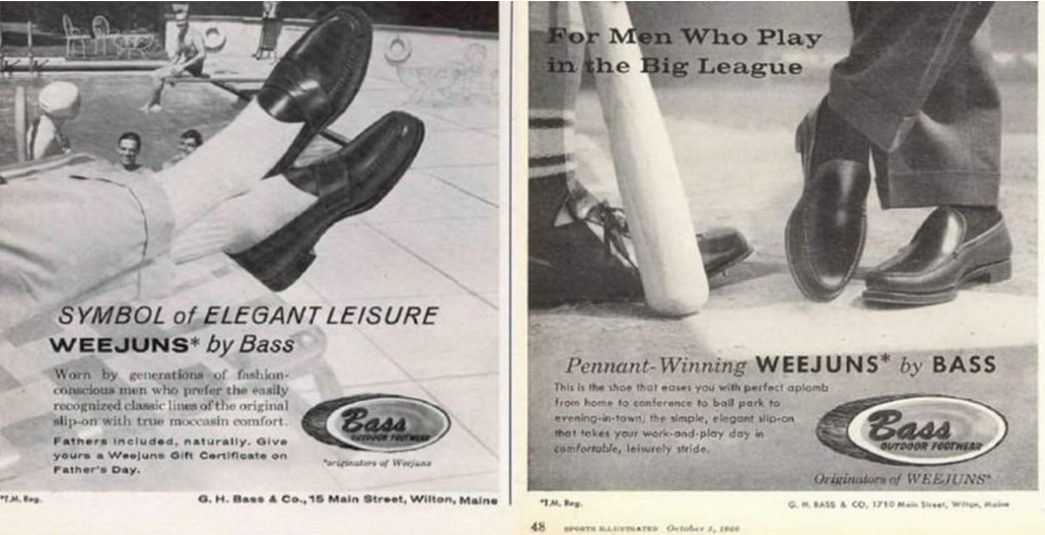

Bass Weejun ads. Image via Gentleman’s Gazette.

Regardless of how it came to have its signature design, the loafer, once invented, made a splash. In the years between the World Wars, members of the so-called “Lost Generation” found themselves incorporating exotic fabrics and designs into their wardrobes. The Norwegian loafers were an obvious hit with them and the first of these shoes began trickling back to America.

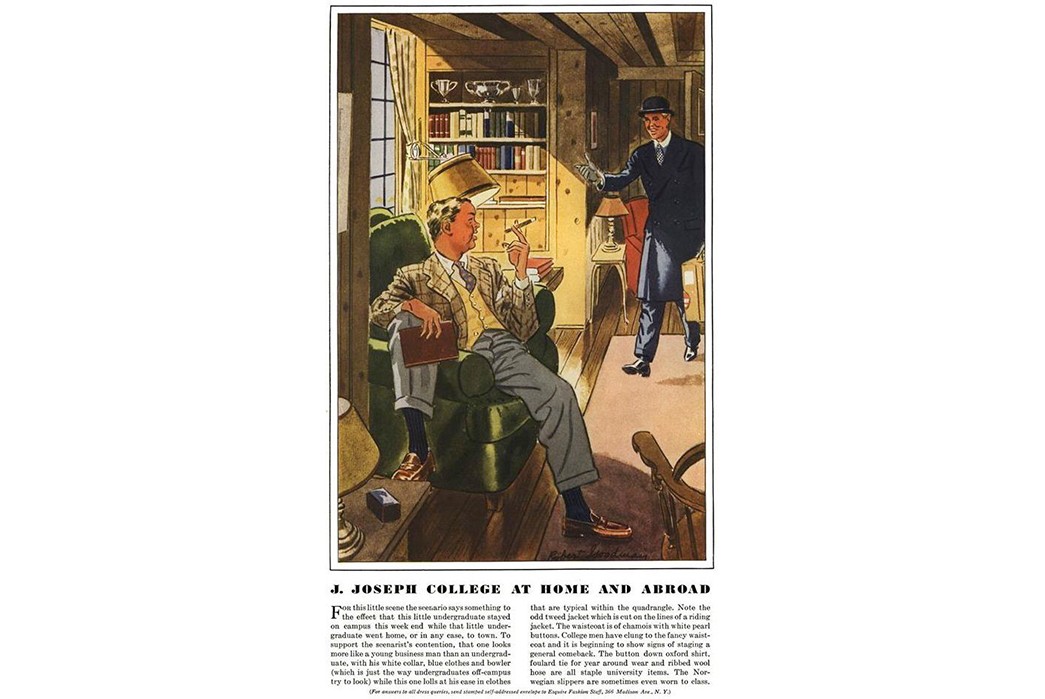

Esquire builds the hype. Image via Esquire.

Esquire noticed the “Norwegian peasant slipper” abroad and the sudden appearance of similar slip-ons at many of the country’s trendiest locales during the summer season of 1934 and ’35. Retailer Roger Peet and representatives of the magazine contacted shoe brand G.H. Bass with a business idea. Despite some concern by the owner, John R. Bass, the new shoe arrived in 1936, now named the “Weejun” (as in Norwegian). Worn by intellectuals abroad and resort-goers at home, the loafer was a far cry from anything resembling peasants’ shoes.

Bass’s most important addition to the loafer was the addition of a crescent slot on the leather band across the upper. Rumors abound about why people first started putting pennies in these slots, but one of the more plausible reasons out there is that people started by placing dimes for phone calls in their shoes, but switched to copper pennies for purely aesthetic reasons.

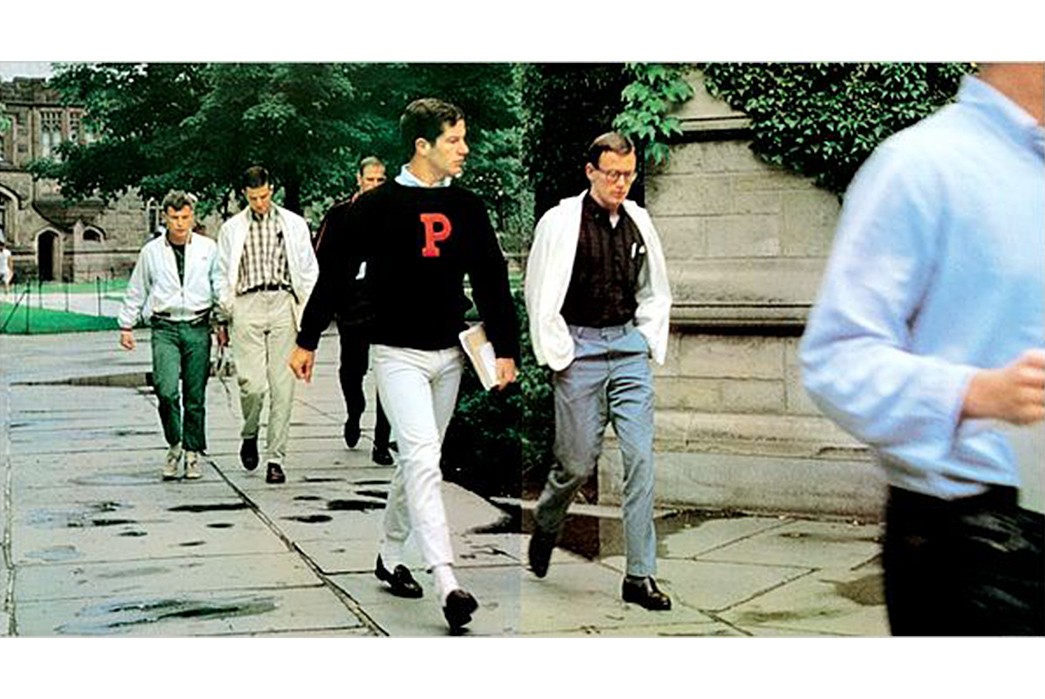

Ivy Style. Image via Teruyoshi Hayashida and Powerhouse Books

The loafer’s next step was taken on college campuses. The postwar college students in the U.S bonded with the comfy, no-frills loafer. Although worn by privileged students in acclaimed universities, this was a humbler moment for the loafer. College students, no matter the era, are notoriously frugal, and loafers were cheap and held up well. But things changed when these college students grew up and took their places in some of the most powerful industries of the nation.

Alden’s tassel loafers. Image via castleberry

The 1950s saw more and more loafers slipped onto famous feet. The first significant addition to the loafer since its arrival in the states was the tassel. Hungarian actor, Paul Lukas, sought someone to reproduce a favorite pair of tassel shoes he’d found while abroad, and it was ultimately Brooks Brothers and Alden who rose to the challenge, collaborating on the design of the above shoe. The first wave of these shoes arrived in 1952, at which point they were often two-toned and popular among Hollywood’s hip set. The simple version above was first carried in 1957 at Brooks Brothers stores across the country.

It wasn’t long before tassel loafers took on a new meaning. By the 1980s, they came to pejoratively signify elitist politicians, lawyers, and businessmen. The New York Times‘s history of the tassel loafer recalls its trajectory from weekend- and vacation-wear to becoming a fixture in the lobbying world of Washington, D.C. In fact, right-wing French voters took to wearing tassel loafers in the 80s to signify their distaste with socialism and their lust for American capitalism.

Loafers are Fashionable

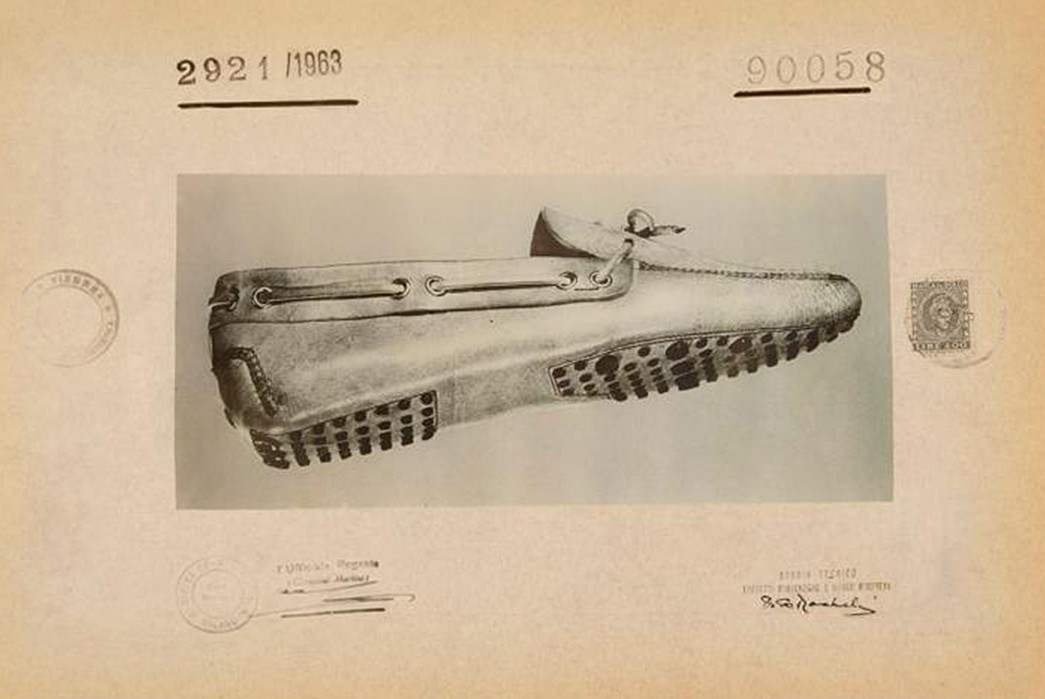

Driving Shoe 1963. Image via lbardi.

The union of Norwegian and Native American design had birthed the original loafer, but its evolution had been symptomatic of uniquely American kinds of class and industry. However, two new members of the loafer family were of more European origins.

In 1963, Gianni Mostile patented the above driving shoe. It had many of the characteristic details of a loafer, with one notable exception, the outsole. Instead, this shoe came balanced on rubber “pebbles,” which gave better grip on the pedals of Italy’s newest generation of cramped, but sporty little cars. Their connection to the glamorous new Italian sports cars and their debonair drivers gave them an allure that belied their unconventional design.

Horsebit Gucci Loafer. Image via Ivy Style.

Gucci, when designing his own interpretation of the loafer, added a unique detail: the horse bit. This newest detail made the shoe a fashion must-have, but also fully cemented its place among the one-percent. Guccio Gucci — who worked at the Savoy Hotel in London as a young man — knew how important horses were to the upper crust. This equestrian imagery had sway with the wealthy men who already wore loafers, but who also wanted something slightly gaudier to show off.

The Final Say

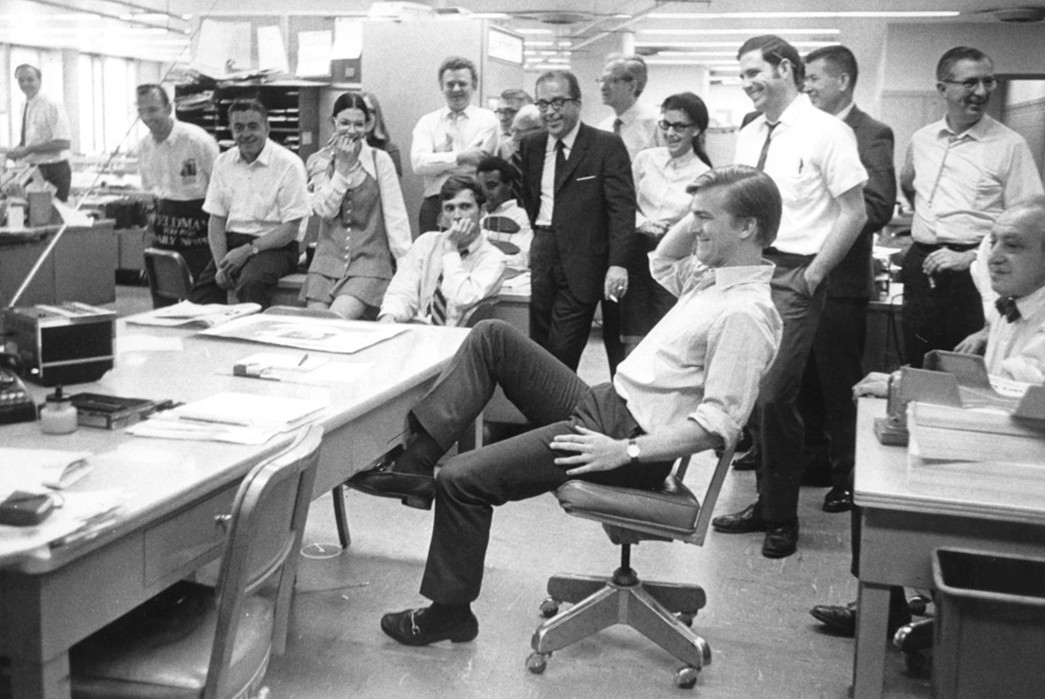

Esquire magazine. Image via Esquire.

Few items of clothing have become so synonymous with power and prestige than this deceptively simple little shoe. Though it draws heavily from Native American footwear, the loafer was thoroughly whitewashed, and its Scandinavian ancestry emphasized by Esquire and GH Bass upon its arrival in the U.S. With minor exceptions, this shoe was worn by the leisure class: first in Florida resorts, Hollywood red carpets, and then D.C.

And because the loafer was primarily about leisure, many industry insiders were initially skeptical that it could succeed. John H. Bass went on record saying, “I didn’t think this type would go over, for it looked like a house slipper to be worn outdoors.” The shoe was impractical, but that was its power. It was comfortable and laid back and its inclusion in board rooms was just as much about ease of wear as it was a subtextual F-you to those whose work requires laces.

In many ways, the history of the loafer is the antithesis of your average Heddels story. Unlike Levi’s or Red Wing, the loafer was never really a practical shoe. Although it had practical applications in the distant past, the style of shoe that Esquire first spotted on vacationers was an affectation and remained so.