There are few among us who haven’t railed against foreign sweatshops to some hapless fast fashion shopper.

Even as some of the giants of American manufacturing succumb to an unforgiving marketplace and corporate profit margins, we tout the importance of American- and other ethically-made clothing whenever we have the chance. Although it is difficult to generalize about workplace conditions for America’s garment-workers, whatever quality of living they have today can be attributed to a long and arduous battle fought since the dawn of the made-to-wear clothing industry. A battle fought by men and (mostly) women that, in many places, continues to this day.

We salute American garment workers, past and present, as we rundown a history of the labor rights of garment workers in the United States.

The Dawn of Industrialization

The first unwilling customers of America’s ready-to-wear industry. Image via Mesda Journal.

The first chapter of our story begins with absolute least ethical system of labor imaginable, slavery. In the American south, slaves were typically given a meager fabric allowance and had been in charge of assembling their own clothes. But in the mid-1800s some slave-owners began contracting out to northern cities to have ready-to-wear clothes made for slaves. Clothing factories produced cheap, shoddy uniforms on a large scale and shipped south.

This allowed southern farm owners to force their slaves to work even more time in the fields instead of on their own clothing. In the north, however, this new mass market created some of the first mass factories to keep up with the demand.

One of the Lowell Mill girls. Image via Sun Associates Archived Resources.

Ready-to-wear became cheaper and more available with major technological advances during the Age of Industrialization. Inventions we take for granted today like the sewing machine and mechanical looms hugely sped up the garment-making process.

By 1840, Francis Cabot Lowell had some 8,000 women working in his mills in Massachusetts. Being a so-called “Lowell Girl” offered many women their first chance to live away from home and experience life away from the often male-controlled household. Entering the workplace allowed women some newfound opportunities, but they were expected to work ungodly hours in dangerous conditions and received about half the pay of their male counterparts.

1843 would mark the first major American step to better the lives of garment-workers when some of the Lowell Girls united to form the Lowell Female Labor Reform Organization. The women of the LFLRA came before the state legislature to educate their lawmakers of the actual conditions within the factories and petitioned for a 10 hour work day.

New Century, Same Shit

Union Soldiers. Ohio History Central.

Unfortunately, reform is easily delayed by those in power and a particularly bloody excuse came with the advent of the Civil War. Thousands of young men were mobilized to battle thousands of other young men over the presence of slavery in the American South and they all needed something to wear.

The North had far more in the way of infrastructure and industry and therefore their troops were much better-equipped. The newly-created garment-making technologies were used to create uniforms that were well, uniform. In fact, it was during the Civil War that modern sizing was invented: small, medium, large, etc.

Immigrant family works in a tenement. Image via Pinterest.

A huge influx of poor immigrants during and after the Civil War created a huge, desperate workforce. Many of these immigrants found work in the garment industry, either in factories or at home in their own cramped tenements. While some families were able to move up in the industry and establish their own businesses, others died of disease and exhaustion. The country was getting acclimated to this new, relatively fast fashion and at the same time desensitized to the conditions of the workers making their clothes.

International Lady Garment Workers Union. Image via United Healthcare Workers West.

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, labor federations began forming to protect workers’ rights, but many of these organizations were tailored exclusively to white male workers. Strikes by black laundresses in the former slave states and the formation of the United Garment Workers of America set the stage for the arrival of one of the most important and progressive unions in American history: The International Lady Garment Workers Union.

The ILGWU formed in 1900, but its early years were fraught. Its members were largely immigrants; some Jewish, some socialist and the ILGWU struggled to create a unified front among the pre-existing unions that had been brought into the fold of the newer, larger union. Their first success came in 1907 with the favorable conclusion of a series of reefer-maker strikes in New York City. (A reefer was a child’s coat, and had nothing to do with marijuana.) By the end, the Reefer Manufacturers’ Association agreed to hire union workers, stop subcontracting, provide equipment, and limit the work week to 55 hours.

The Uprising of the 20,000. Image via Reading Rambo.

1909 brought another huge strike that garnered national attention. “The Uprising” was a movement of 20,000 garment workers (mostly female shirtwaist-makers) who began by protesting the dismissal of union workers from a shirtwaist factory. And as in many other factories, excessive hours, unsanitary conditions, and unfair pay seriously impinged on garment-workers’ quality of life.

The largely immigrant communities who started this movement gained support from middle class women as well, because of their outspoken views of women’s suffrage. The Uprising was successful not only because of the ILGWU, but because women across New York City were able to unite under common goals, despite differences in culture, creed, and class.

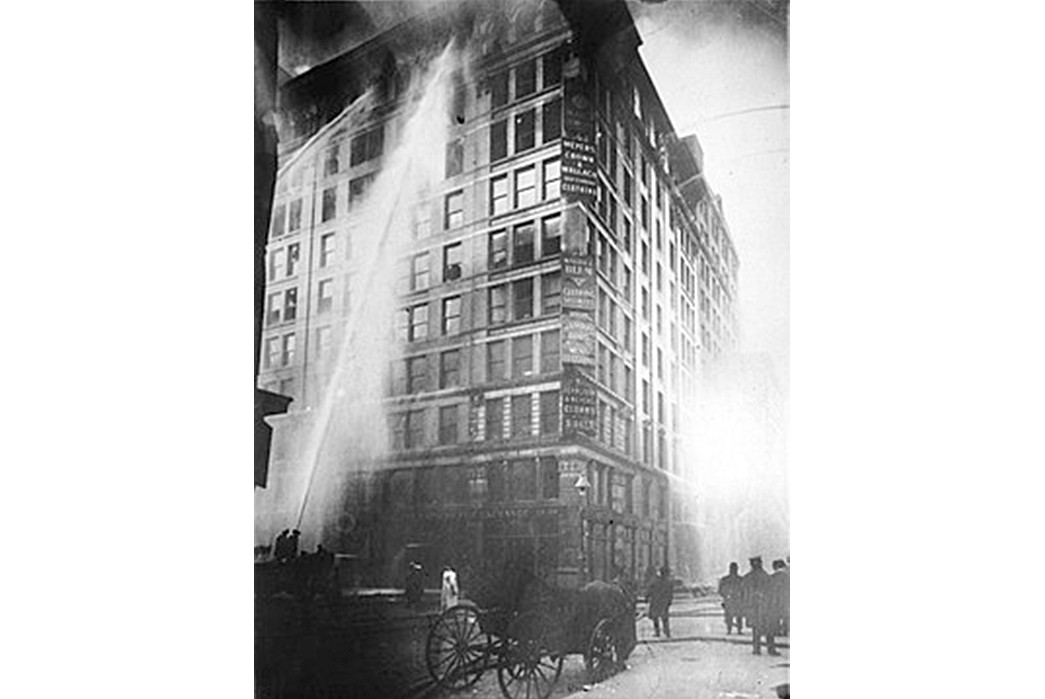

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Image via Cornell University.

The Uprising may have helped the nation at large understand more about the inhumane conditions of garment-work, but it would take a huge tragedy to enact change.

On March 25, 1911, a fire started in a scrap waste bin on the eighth floor of a shirtwaist factory in New York’s Greenwich Village neighborhood. The factory owners had locked most of the exits to prevent workers from stealing and the already-cramped facilities lacked proper emergency supplies, so when the fire broke out, escape was impossible. Within minutes, fire had spread to the ninth and tenth floors and the minimal fire escapes became unusable or collapsed onto the street. Fire ladders were only able to reach the sixth floor while dozens of workers remained trapped inside. 146 garment workers died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.

These deaths were impossible for politicians to ignore and led to the first wave of major changes in labor rights in the American garment industry. Reformers and law-makers joined forces to create the Factory Investigation Commission, which, only two years later had helped write 25 bills into law. We can thank the Commission for laws about automatic sprinklers, fire drills, and a greater degree of safety in most modern buildings.

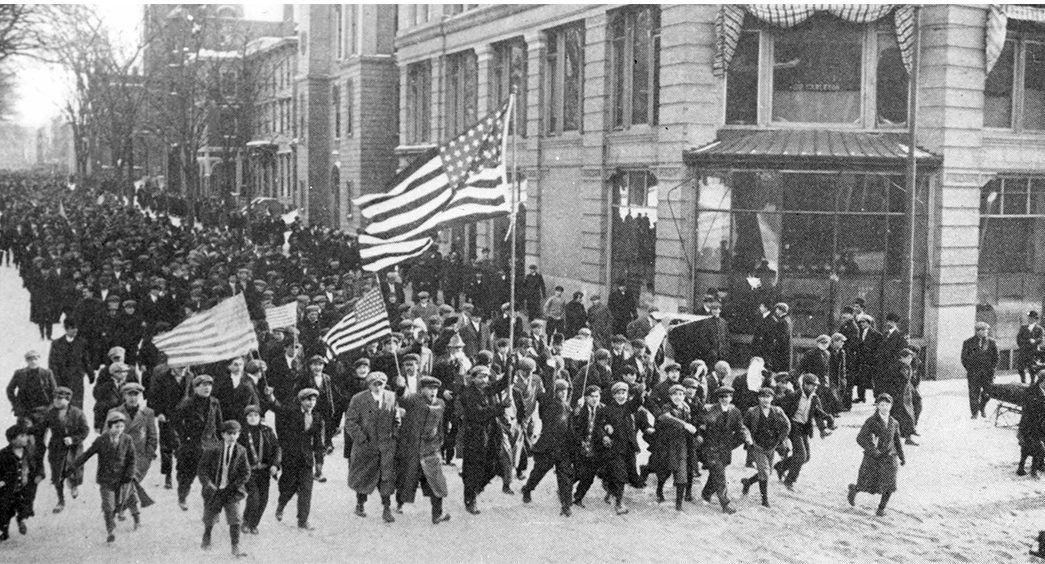

The Bread and Roses Strike. Image via New England Historical Society.

The year after the fire, another major labor precedent was set, this time in Massachusetts. The city of Lawrence exploded into chaos when garment workers’ pay was abruptly cut. Thousands of strikers took to the streets and the city became so dangerous that hundreds of children had to be shipped out to New York via train to wait out the storm. The huge mobilization of workers in what came to be known as the “Bread and Roses” strike, led to the creation of the Department of Labor and the adoption of minimum wage laws.

Eleanor Roosevelt with the ILGWU. Image via Flickr.

World War I helped to briefly boost the garment industry, but The Great Depression didn’t do any favors to the country’s already-disadvantaged union-members. Salvation came with the Roosevelt-era New Deal that included the rights to organize and bargain collectively. The ILGWU saw a significant uptick in credibility and membership when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt aligned herself with women’s labor rights.

Laborers of all stripes were fighting for their most basic rights. Coal miners, laundresses, porters, and steel workers of all races and genders took part in this battle. The garment workers were unique in that they were most often a very particular demographic; female Italian and Jewish immigrants.

Image via Labor Arts.

Disposable postwar income and a huge new wave of immigration led to many sweatshops opening in the U.S. in the 50s and 60s. Americans could suddenly afford to buy more clothing and the garment industry stepped up production to meet demand. While sweatshops still exist in the U.S., the majority of manufacturing was outsourced in the 80s and 90s as companies attempted to dodge the minimum wage laws that labor unions had fought so hard to establish.

The ILGWU expanded their focus in the 60s to include healthcare and housing. The 1960s brought new challenges to the Union, but also some landmark legal decisions. 1963’s Equal Pay Act made it illegal to pay men and women different wages for the same work and the 1969 decision by the The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission declared “protection” legislation that had kept women out of certain professions to be invalid.

Garment Labor Laws Today

Garment workers in Bangladesh. Image via YAA.

The long struggle of garment workers have insured that there is now far more stability and safety in American garment manufacturing facilities. The Department of Labor has established strict guidelines about minimum wage and overtime. All apparel contractors must follow the rules set in The Fair Labor Standards Act. The Act prohibits minors under 16 from working in apparel and prohibits the commercial manufacture of clothing at home.

Garment workers today cater to a clientele that is more accustomed than ever to instant gratification in their shopping. Far too often, the average consumer forgets the human face and hands behind their clothes and choose options that are more dubious than others. China, which had long been derided for its association with sweatshops, is slowly becoming too pricy for clothing manufacturers who only care about the bottom-line. Many are now moving to places like East Africa and Bangladesh, where wages are lower and labor laws much laxer. in 2013, over a century after the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, lax regulations at the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh lead the building to collapse, killing 1,134 garment workers.

Life is by no means easy for American workers in the garment business and there is still much work to be done in fair labor policy, but the comparative progress is staggering. We must continue to advocate for progressive labor policy as well as direct our hard-earned earnings to brands that support and care for workers.

Thank you to those of you who make our clothes. We cherish you and appreciate your work.