What do you think of when you see “Made in USA” on a clothing label? Do you picture someone in a sunlit workshop, taking measured care over every stitch like Michelangelo with a piece of marble? Do you see people punching in for a forty-hour week that provides them a decent wage, benefits, and a safe and respectful working environment? Are you imagining a mythical attention to detail and quality that was cast aside by modern mass production? Do the values of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” shine through the label?

That’s what I used to think. This was about ten years ago before I began writing here and the Made in USA movement was just heating up. My only points of reference were movies, marketing materials, and websites similar to this one. They led me to a clear dichotomy: “Made in USA/Western Europe/Japan” = Artisanal; “Made Everywhere Else” = Sweatshop.

In reality, though, it’s not so simple.

I’ve since had the opportunity to visit dozens of manufacturing facilities all over the world. I’ve seen some of the most freewheeling artisanal studios in the United States and I’ve also seen sweatshops operating just a few blocks down the same street.

There’s no hard and fast rule that “Made in America” guarantees you a quality fairly produced garment and “Made in India” a crappy and cruel one. Buying something purely because it was made in a particular country doesn’t make you a smarter or more ethical consumer, it makes you a nationalist. Many are reducing what they look for in clothing to a single checkbox, “Was it made in America?”

Let’s reflect on what “Made in America” means at 242 years old.

When it Was All Made in USA

Garment workers in New York City’s Garment District move clothing between factories in 1955. Image via New York World Telegram.

As recently as the 1960s, 95% of clothing bought in the United States was made in the United States. But the American economy evolved and sent nearly all of that manufacturing overseas by the end of the 1990s. The price of import fees and shipping from abroad was more than covered by the savings in labor cost. As of 2013, Americans produce less than 3% of the clothing they wear. So it’s no surprise that the portion still made domestically is fetishized.

As any regular reader of this site knows, American-made goods come at a premium. But are they actually better? It’s difficult to compare designer clothing, so let’s consider something that’s more of a commodity like blank t-shirts. A Made in Honduras Gildan white t-shirt wholesales for about $2, the equivalent American tee is $8. Is “Made in America” worth 400% more money as a consumer? Because it costs at least that much more to produce it.

A Honduras made Gildan (left) and a much more somber American made US Blanks tee (right). Image via Shirt Space.

There are multiple reasons as to why manufacturing in the U.S. is that much more costly. The obvious ones are labor is more expensive, regulations are stricter, rent is higher, etc. But beneath the surface, American manufacturing facilities and machinery haven’t had an upgrade in decades. When all the work went overseas, there was never any reason to invest in what was left at home. Manufacturing technology in “developing countries” is lightyears ahead of what’s still on the factory line in America. As a result, not only is labor more expensive in the U.S. but a lot more of it is required to make the same garment.

Yet there can be a real artistry in that extra labor on these old machines. You can see it in brands like Roy, Railcar Fine Goods, Raleigh Denim, and many of the others we feature who make quality garments, in-house, on vintage machines. This kind of company is the shining star of Made in America and they are the ones actually carrying out the fantasy described at the beginning of the article. The people who own and work at these companies are passionate about what they do and the specific garments they create.

Raleigh Denim Workshop in North Carolina. Image via Raleigh Denim.

That’s why we love them and why we think what they make is worth your attention. But they are the exception and not the rule for a garment factory in the United States or anywhere else. A typical contract production facility in the U.S. (like the one that produced the $8 t-shirt) likely looks a lot more like your idea of a sweatshop than the idealized American factory.

An inmate makes flags at the Maryland House of Corrections. Image via KTLJ.

The real benefits of making in the U.S. are the lower barriers to entry for small American designers. The minimums are lower, the factories are more accessible, turnarounds can be faster, the language and culture barrier is more manageable (even though the majority of garments made here are made by immigrants). A new brand can get their start with less experience and less money than what they’d need overseas while keeping a closer eye on quality control. The flip side is that manufacturing is more expensive and limited to the equipment and people available.

For most small brands, that’s the long and short of why they manufacture in America. There’s nothing special inside the imaginary line of the border that makes things produced in the U.S. better. There are factories in contract Guangzhou, China can produce a pair of selvedge raw denim jeans that’s just as good as any contract factory in Los Angeles. But the reason Chinese factories don’t make high-quality garments isn’t because they can’t; it’s because no one wants to pay them to do so. Most of the brands that want high-quality production are located outside of China and their order numbers are low enough that it’s cheaper and easier to work with a factory closer to where they’re based.

It may seem like the things that are Made in America are better, but that’s often correlation and not causation. The brands producing in the United States are already aiming at a higher price point and require a higher level of quality to justify the price tag, so they work very hard to get it from American factories.

Automated in America

A pair of jeans is distressed via laser-etching robots. Image via Fibre2Fashion.

It’s our hope that more and more people buy their apparel and other goods from the Raleighs and Shockoes of the world, but it will likely always be relegated to a niche audience who want to take the time to understand, appreciate, and pay for it. The vast majority of people will likely always buy clothes made by the systems of mass production that currently operate overseas.

However, there’s a rapidly developing labor source that’s about to be much much cheaper than nearly any workers found abroad, that of automated machines.

Levi’s announced in February that they’ll be switching over almost exclusively to laser robots distressing their denim, and that they’ll be doing it much closer to the point of sale (meaning it will happen in the U.S. and Europe). Typically the production cycle on a mass produced pair of jeans takes months and has to happen all in sequence: cutting, sewing, distressing, washing, finishing, etc. This all amounts to designers having to schedule the finished product nearly a year in advance, hoping they’ll hit the trend correctly by the time the garment is done. Finishing near the point of sale allows Levi’s to break up that process and zap whatever’s trendy at the moment into a blank pair of jeans just days in advance of it hitting store shelves.

This is good because even though distressing is never ideal, lasers are more environmentally friendly than conventional distressing and finalizing the design right before sale means it’s more likely to sell and less likely to end up in closeouts or a landfill.

Workers create fake fades at a denim wash house in Kentucky. Image via David Friedman.

The complication is there are hundreds of thousands of people around the world that currently earn a living grinding, sandpapering, and otherwise distressing jeans who will soon be made obsolete. Robots will come for the rest of the production process shortly thereafter. Jobs likely will come back to America, yes, but many more of them will simply disappear. The factory of the future doesn’t have hundreds of people on sewing machines but rather several dozen robots and a handful of human technicians that maintain them.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Mass garment production is usually monotonous and repetitive work that forces people to act as robots. Facilities often operate on “piecework”, meaning they pay their employees based on how many buttons they attach or sleeve cuffs they sew. Instead of making a garment from start to finish, someone will do the same step in the process over and over and over again. I once visited a factory where a woman sewed breast pockets onto shirts (and only breast pockets onto shirts)…eight hours a day, five days a week, for thirty years. The fewer people required to do a single tedious task for the majority of their lives, the better.

The conundrum is what will those people put out of work will do? That’s a far more complex topic than the scope of this piece but something nearly every sector of the economy will have to reckon with.

Idealized Independence

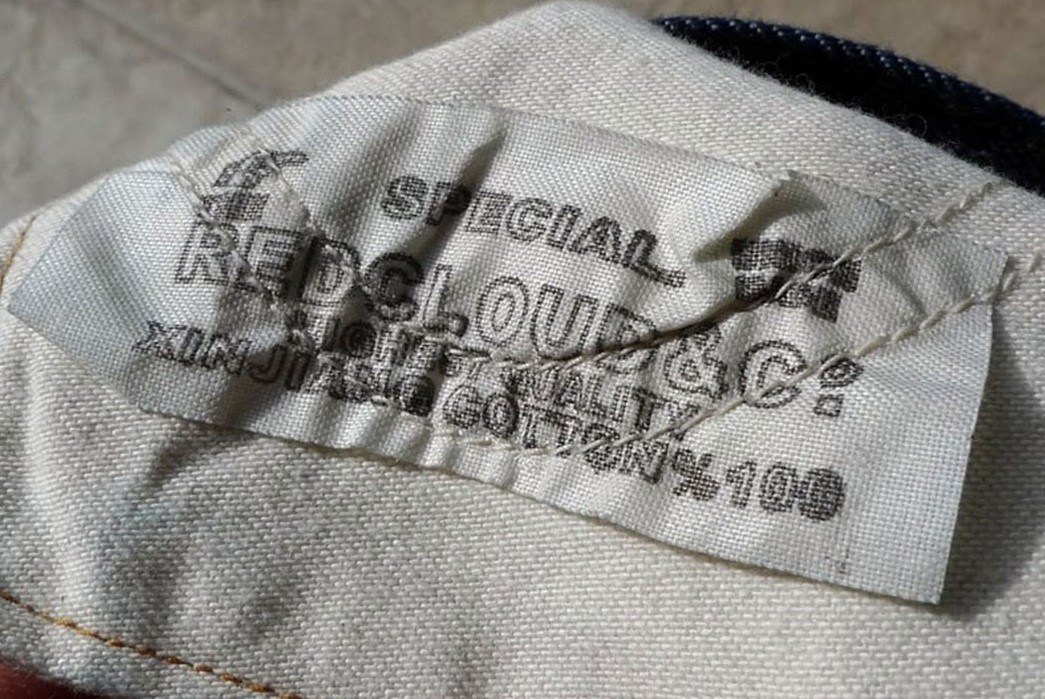

Red Cloud jeans, made in China from Chinese Xinjiang cotton.

So we’re back at the beginning—what does Made in America actually mean versus what do we want it to mean?

A professor of mine was once asked, “What’s a degree from our college worth?” and he replied, “It’s worth as much as the least noteworthy person who has one.” I feel similarly about Made in USA. The only fraternity Made in USA garments share is that they were all (mostly) made within the U.S. border. Any idealizations you may have about what that means should be taken with a boulder of salt because that grouping includes a lovingly crafted pair of Roy jeans as well as a tee created with essentially slave labor in a private prison.

That doesn’t mean those idealizations aren’t important. They give us something to aspire towards. For me, I try to make sure everything I consume is made under the following conditions:

- Wages that can support housing, essentials, and medical care for all workers

- Safe and tolerant working conditions, free of child and forced labor, where grievances can be addressed collectively

- Minimal environmental impact and use of resources in relation to the longevity of the finished product (i.e. a leather jacket is much more resource intensive than a cotton one, but will presumably last much longer)

These qualities aren’t exclusive to the United States and can be found anywhere on the planet. Oversight to make sure they are carried out becomes more difficult the farther one gets from home, but what’s actually at the core of this Made in America fantasy can exist in Pennsylvania, Portugal, or Paraguay.

A worker at Unmarked’s factory in Mexico inspects boots. Image via Unmarked.

And there are many artisanal techniques where the best work can only be done in developing countries. Japanese brand Visvim manufactures nearly all of their hand-welted footwear in China not because it’s cheaper, but because that’s where they can produce the highest quality product. Similarly, American brand Yuketen makes a lot of their boots in Mexico because some of the best western style shoemakers are in Leon. And our next CO-OP collaboration is being made in Pakistan because that’s where a specific indigo block printing method was pioneered over 3,000 years ago and is still in practice today.

It’s not where you make it but how.

Made in America and the Rise of Nationalism

The white nationalist “America First Party” in 1944, which advocated deporting immigrants and ending US involvement in WWII. Image via Weebly.

So cui bono? Who benefits from promoting the Made in America narrative?

“America First” has become a firebrand for conservative politicians and yet their vision for American manufacturing is completely counter to our idealized vision of what Made in America means. They’re opposed to workplace and environmental regulation and safety, against raising the minimum wage, anti-union, and want to repeal even the modest healthcare rights of the Affordable Care Act. They promote themselves as champions of the American worker, but by every metric, the people who tout “America First” are making conditions worse for the people who work there.

To the “America First” crowd, Made in America is just hollow nationalist rhetoric. It creates an imaginary foreign boogeyman, which they can blame for all the problems they themselves are exacerbating.

Remember that Donald Trump, the American president who screams the loudest to “Buy American and Hire American”, produced most of the offerings from his own brand and campaign overseas. And the tariffs of the isolationist trade war he started now costs Americans more than the taxes associated with the Affordable Care Act—and the ACA money actually paid for healthcare benefits for working Americans.

Image via Clark Howard.

This is far more political a post than we typically have on Heddels, but when something so dear to us is hijacked by charlatans who are actively working to harm our community and the world at large, we feel obligated to speak up.

As consumers, we have a responsibility to look beyond the country of origin label to see if what we’re buying actually represents the values and conditions we want to support. And we should be suspicious of anyone who tells us otherwise and blames large systemic problems on simplistic foreign scapegoats.

It’s not where you make it but how, and we’ll continue covering a variety of products made all over the world that represent the values and working conditions we believe in, including those Made in America. But don’t believe me, take a look for yourself.