This is the fourth iteration of our CO-OP series, our collaborations with brands we admire to create limited runs of specialized products exclusively for Heddels readers. By working with the brand, we hope to dive far deeper into who they are and how they operate than we ever could have with a profile. We have an extensive list of rules that we have to abide by for each product to bear the CO-OP label.

Our CO-OP articles serve as the complete documentation of how we created our product, from concept to sales. This article covers the creation process with denim and jeans manufacturer Artistic Fabric & Garment Industries (AFGI) and our fourth collaboration project, the Ajrak Bandana.

Why Artistic Fabric & Garment Industries

When you see the phrase “Made in Pakistan” on a garment, you probably don’t think anything good. I’m guessing you imagine a dimly lit sweatshop, choking with heat and dust, with hundreds of workers churning out thousands of the latest fast fashion whatever for next to no pay. You feel good about setting it back on the shelf in comparison to your discerning Made in USA/Japan/Western Europe equivalent.

I’m guessing you think that way because I also thought that way four years ago. It was summer of 2014 and Nick and I were in Barcelona for Denim by PV, an upstream tradeshow where mainstream brands source the fabric and hardware to make their collections (Gap, Ralph Lauren, Target). We had finished a solid 48 hours of interviews and meet and greets, but our press handler told us there was one more vendor that really wanted to meet with us, Artistic Fabric & Garment Industries (AFGI). “What’s their deal?” Our handler said he wasn’t sure but they were from Pakistan and that someone named Henry wanted to meet us.

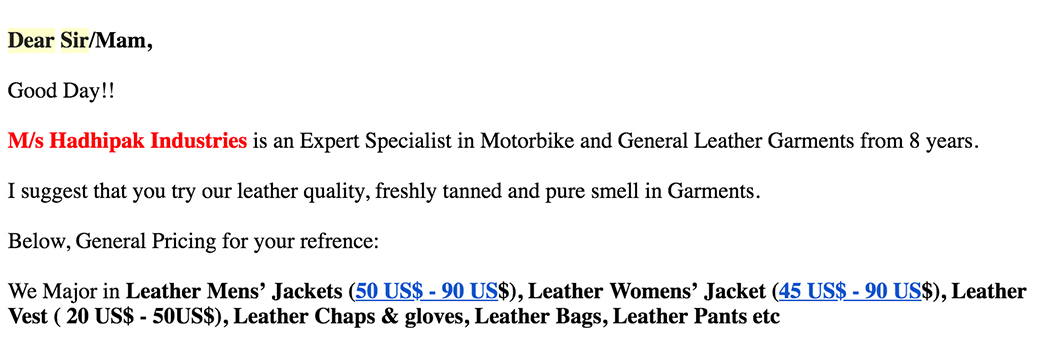

We get hundreds of what I call “Dear Sir” emails every month from manufacturers in India, China, Pakistan and other parts of the developing world. They spam form emails to anyone with even a tangential connection to the fashion business to offer their services in producing blue jeans, leather jackets, soccer jerseys, baby bibs—whatever you want. Here’s an example I just received this week:

I took the meeting thinking we would finally get to see one of these companies in real life. But I could not have been more mistaken.

AFGI is a vertically integrated denim and apparel production company, meaning cotton goes in and jeans come out. They do all the spinning, dyeing, weaving, cutting, sewing, washing, finishing, and even put on the price tags in between. AFGI is big business, they produce about 50 million meters of fabric and 25 million finished garments per year and they are one of the main denim suppliers for Old Navy, The Gap, Wrangler, and H&M.

Those stats are impressive, but as you know, not all that relevant to what we do. Our contact was Henry Wong, AFGI’s head of product development. We’ve published interviews with Henry before, and I have to say, there is no more knowledgeable, passionate, and considerate denimhead in this business than he. What Henry wanted to talk about instead was Ajrak, the traditional Pakistani indigo dyeing technique.

Henry at Denim by PV in 2014.

Henry got into this business purely as an enthusiast. He was one of the first people posting on Superfuture in the early 2000s and widely considered to have coined the term “Osaka 5“. His background was in accounting and he found work doing the books of a denim importing company which he then parlayed into the design side and eventually a job in product development at Cone Mills. After a several year tenure, he found himself doing factory audits in Pakistan and eventually in his current position as the head of product development at AFGI.

An aizome junkie, Henry seeks out indigo wherever he goes. After much asking around in Pakistan, he found Ajrak, one of the oldest (if not the oldest) continuous indigo dye practices in the world. For over 3,000 years, people in the Indus River Valley (present-day interior Sindh, Pakistan) have resist-printed on fabric with tessellating wooden blocks.

One of Henry’s colleagues at AFGI put him in contact with Abdullah Dada, one of the few remaining Ajrak masters. Henry toured the Ajrak studios in Matiari, a small town about 200km inland from Karachi and developed a promotional bandana for AFGI off of some of Abdullah’s excess fabric that was dyed indigo in the warp and yellow persimmon skin in the weft for a rich grey color all over. Henry shared some pictures of Matiari and the Ajrak process.

As someone who’s seen a good deal of “heritage” clothing and textiles, this was one of the deepest stories I had ever heard. Henry lamented that his bandana wasn’t block-printed, but someday he hoped to have a good excuse to develop his own design and block and have something made that’s truly Ajrak.

“When can we start?” I asked, half-joking, but Henry didn’t miss a beat, “If you want to develop something and come out to Pakistan, I’m sure that could be arranged.” I didn’t know if he was only teasing at the time, but it was a meeting I would think over for hours on the flight home.

I would see Henry about a year later at the Kingpins fabric tradeshow in New York. After a few pleasantries and talking through their current lineup, he asked if I still wanted to make that bandana. “Of course!” I replied immediately. We met up later that week and laid out the project.

Heddels would come up with the bandana design, marketing, sales, and documentation, AFGI would provide the manufacturing, product development and interfacing with Abdullah Dada and his artisans, as well as bring me to Pakistan to see the process. I wondered how long this would all take, “Oh, I can’t see it going much past this spring.” It was July of 2015, months before we had announced CO-OP or even the Heddels name.

The Process of Ajrak

The definitive text on the history and process of Ajrak is Sindh Jo Ajrak by the Pakistani artist Noorjehan Bilgrami. In the late 1980s, Bilgrami spent years amongst the Ajrak makers in interior Sindh documenting their patterns, methods, recipes, and the general culture of how an Ajrak is made from start to finish. Henry was kind enough to lend me his copy and I’ve read it at least a dozen times over the course of this project.

Noorjehan Bilgrami. Image via Koel.

Examples of indigo dyeing in the Indus Valley date back to 2500 BCE in the Mohenjo Daro settlement and Ajrak to about 500 BCE. Many cultures argue today about “who did indigo first” some five thousand years ago, and while it can’t be proven definitively that Pakistan/Mohenjo Daro “did it first”, they were definitely one of the oldest independent originators in human prehistory.

The ruins of Mohenjo Daro in southern Pakistan. Image via National Geographic.

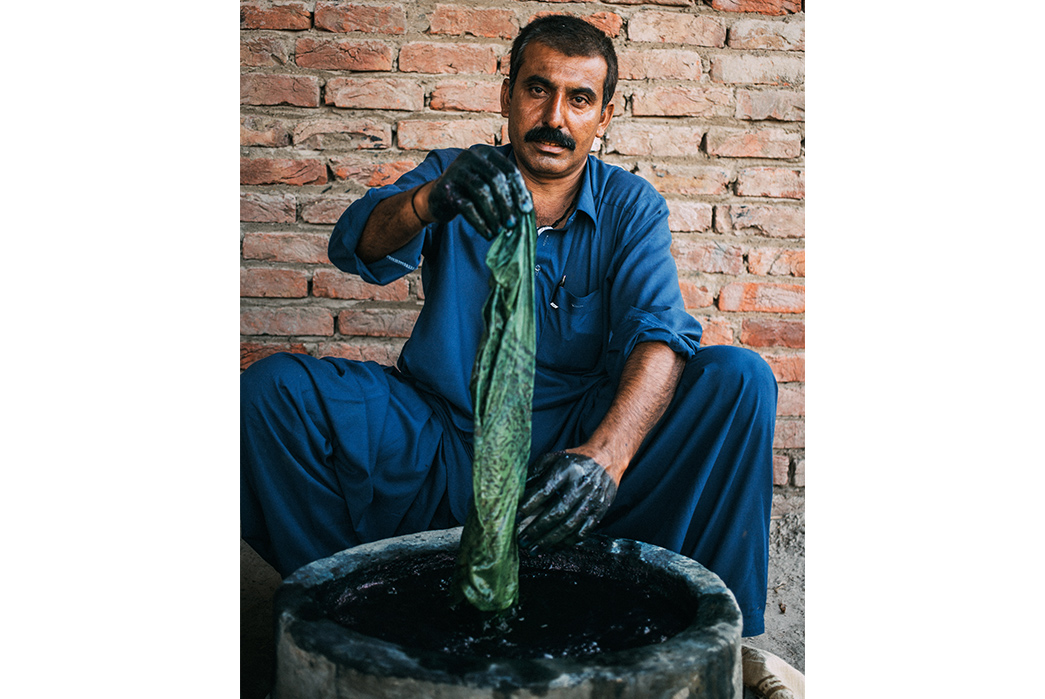

Here’s a basic overview of the Ajrak process: it involves a light, usually plain-woven textile that’s first washed in gissi or fresh camel dung, beaten and dried in the sun. It’s then washed in the river and boiled in a giant cauldron before being dried again.

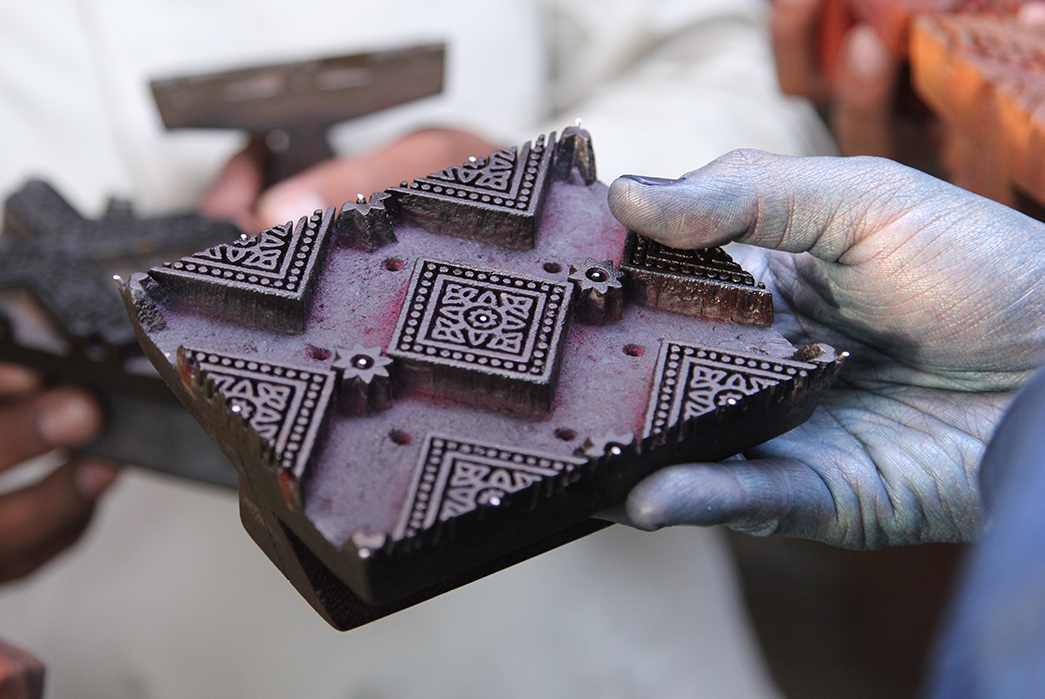

At this point, it’s ready to be printed with carved wooden blocks. Printers dip the blocks in an almond-based henna paste and then stamp the pattern out onto the fabric and let it dry in the sun again.

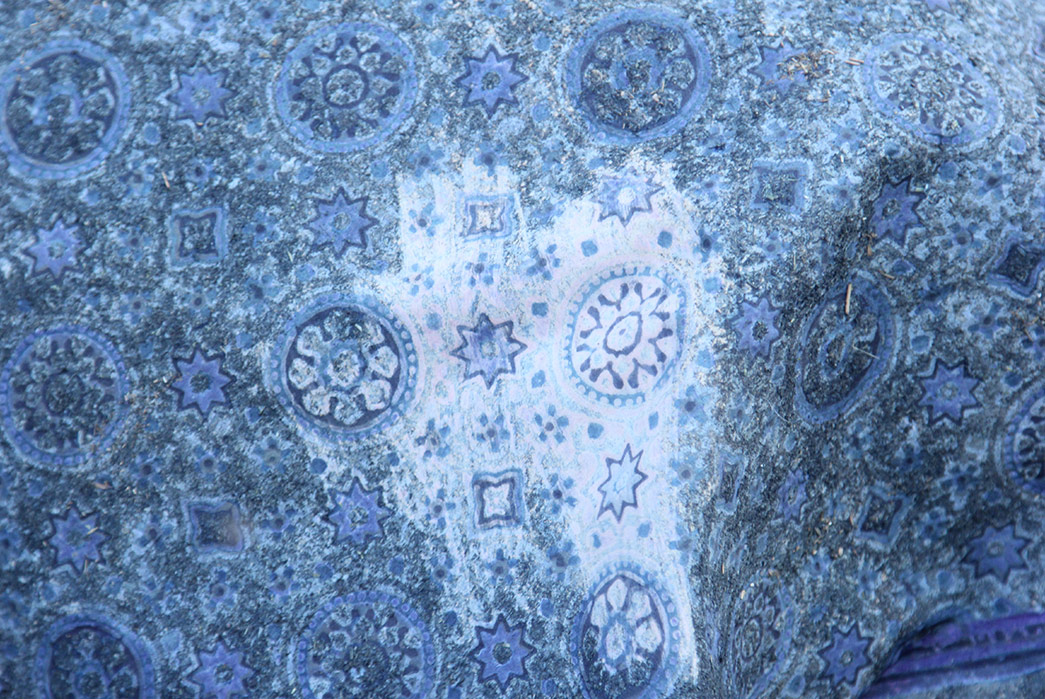

The fabric is vat dyed but the dye resists everywhere the fabric was printed with henna, leaving those places blank. The fabric is then dried again and either finished, ready for another round of indigo, or printed again for another color.

The entire process takes about a month and can contain many more steps depending on the recipe. As you may remember, the indigo dyeing process is quite chemistry intensive, and Ajrak is an incredibly sophisticated process that basically developed via trial and error over thousands of years. Many of these dye recipes are passed down orally and remain closely guarded secrets amongst specific families and regions.

Ajrak Designs and History

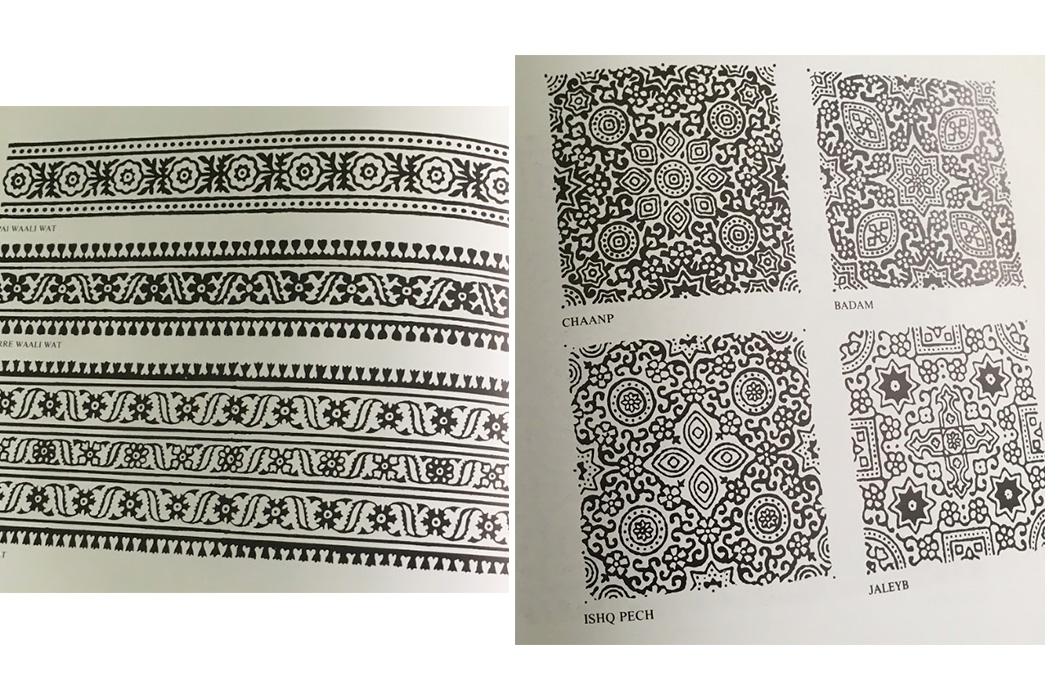

Like all arts, in Ajrak the medium informs the design. Pattern makers are as much architects as they are designers as the finished product has to be transcribed in wood, which has its own limitations.

To make the wood block stronger and last longer, the design itself is relatively homogenous in terms of line concentration–i.e. there’s an equal amount of lines/information in all parts of the block–because a big gap or a loose strut or a thin piece would be much more likely to chip out during the carving or later printing processes (some of these blocks are used to print for hundreds of years).

So all of the lines usually are thick and solid and connected. When things stand alone, they’re at least BB-sized dots because anything smaller would chip out during carving.

The Art

Now we had to come up with our own imagery. We had Abdullah Dada to guide us and his best carvers would be translating whatever image we created into a set of wooden printing blocks to dye the bandana. I enlisted the help of artist and textile pattern designer Milan DelVecchio to create the art.

We wanted to make something that read immediately as a bandana but was composed of traditional Ajrak patterns and imagery. Noorjehan Bilgrami’s book was exceedingly helpful in understanding some of the core Ajrak styles.

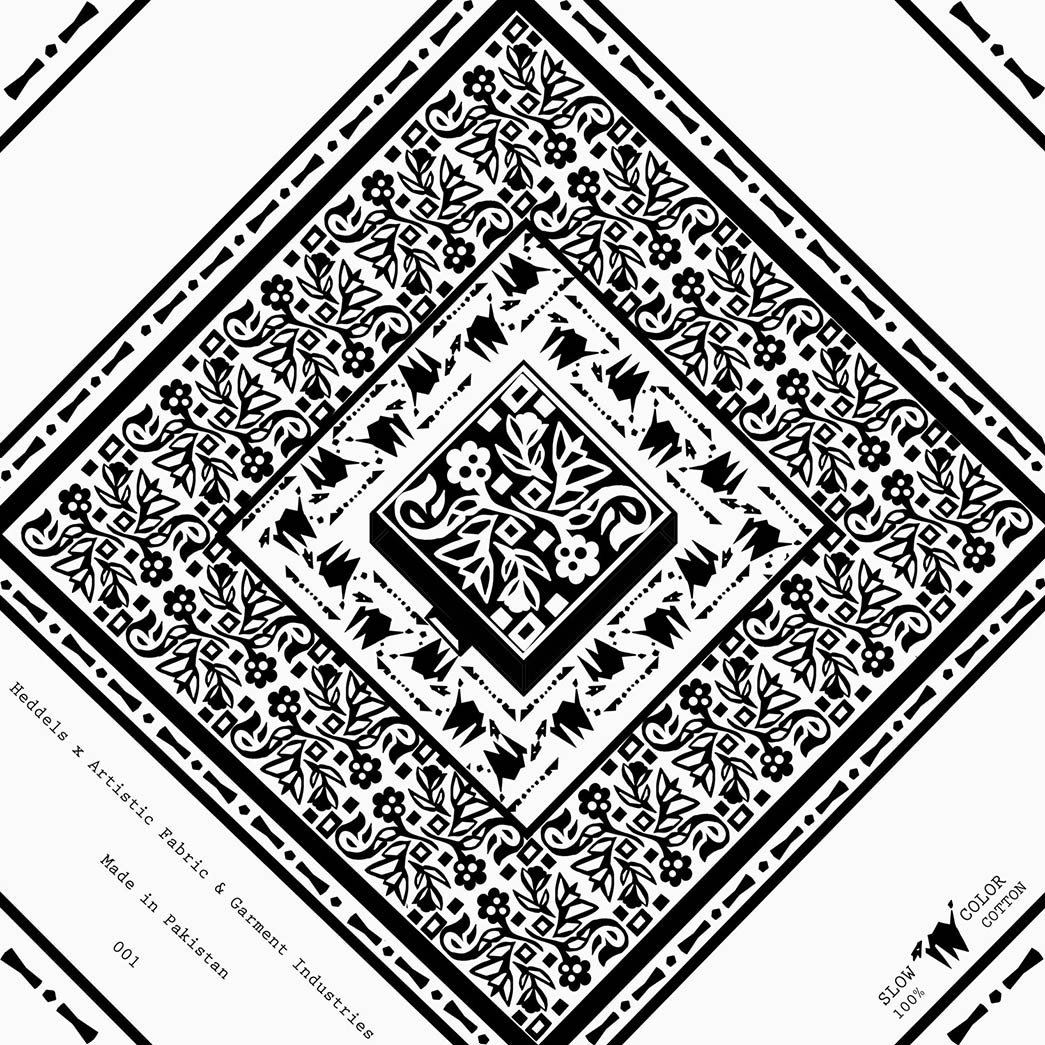

I knew that if we just tried to do our own traditional Ajrak design, it would be disingenuous and pale in comparison to what they’ve been producing in Sindh for the last three thousand years. Instead, the concept we came up with was a little René Magritte, but instead of “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” it would be “This is not an Ajrak (but actually it is an Ajrak).”

Ajrak designs are typically all radial symmetry and right angles. There’s a central floral motif that expands outwards so it can tessellate with repeated printings of itself. It all lines up seamlessly so you have this enormous six-by-eight foot textile that looks like one cohesive print but it’s actually composed of hundreds of stamps of four-by-four inch blocks.

But we wanted to call attention to the methods and techniques used to produce our bandana, so our central motif is actually an asymmetrical image of the block itself–it’s like a rubber stamp that stamps an image of a rubber stamp!

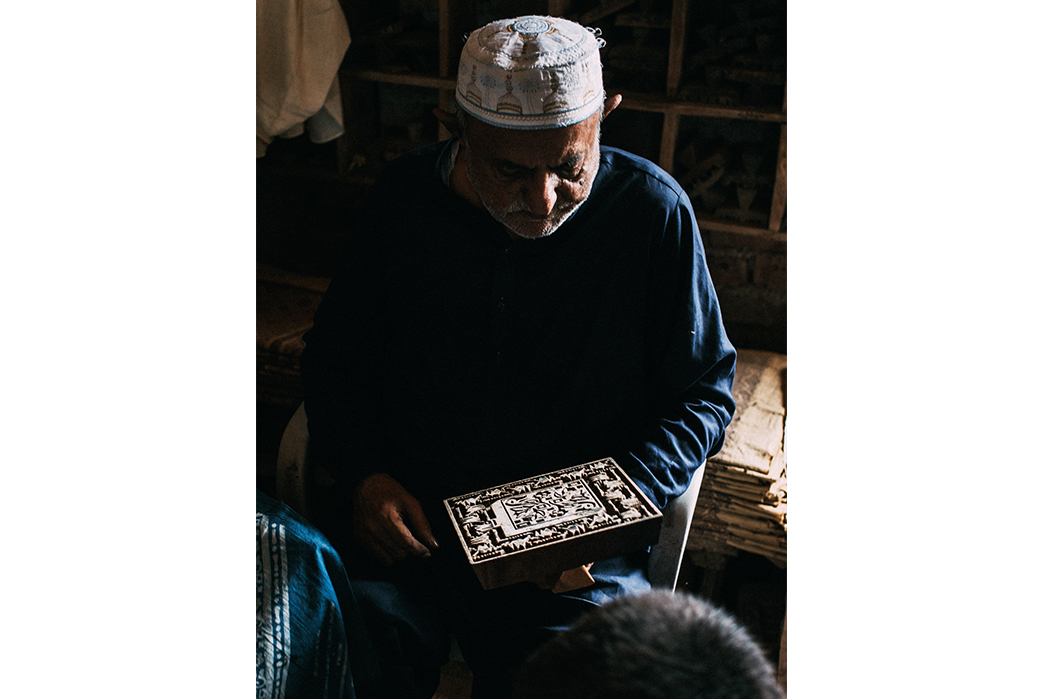

Abdullah Dada inspecting our main Ajrak block.

The specific imagery itself we wanted to delve even deeper into the story of Ajrak. The floral pattern in that central block is an Indigofera tinctoria flower (indigo) and the branch of an Indicus arabica tree, the species of wood used to carve the printing blocks.

Around the inner border surrounding the central block depicts another integral piece of the Ajrak process–camel dung! Our pooping camels represent the gissi needed to prepare the fabric for printing. The outer border shows the inverse of the central block as if it had been printed and tessellated traditionally. The whole thing is finally surrounded by a thin outer border of simplified thoknis and awls, the traditional wooden mallet used to carve printing blocks.

The camel is repeated in the outside corner of the design, neck up in a nod to vintage Elephant brand bandanas from the early twentieth century. And our brand name and “Made in Pakistan” are printed in the opposite corner, all the lettering mirrored and carved by hand for printing.

The image we finally delivered was an Adobe Illustrator file, but that’s not exactly in the workflow of an Ajrak artisan. AFGI printed off a to-scale image of our design, which the carvers used to create the blocks directly. Now we just had to wait until everything was ready for us to go to Pakistan and see the process for ourselves.

Pakistan

Now you may not know this, but Pakistan doesn’t exactly have the best reputation as a destination for the western world. Pretty much everyone I told that I was going responded with a shocked “Is it safe?!”, “Why would you go there?”, “You’ll get beheaded by Al Qaeda!”, etc. etc. A well-meaning relative even offered me his Glock for the trip (I politely declined). If an American can even find Pakistan on the map, the first thing they probably know about is that’s where Osama bin Laden was found in 2011. It’s at once portrayed as a country as violent as Iraq and as repressive as Saudi Arabia.

I have to admit, I didn’t really know what to expect going into it and it took some convincing for our frequent video collaborator Ryan Lindow to join me. What I found could not have been further from that representation. Pakistan is one of the most welcoming and friendly places I have ever visited. Everyone was so generous and genuinely excited to see that I was visiting their country. I am not nearly well informed enough to speak to the greater geopolitics in the region, but my personal experience was incredible and I never felt like I was in danger. The only real threat was the water, and I did get a bit of food poisoning from a shinkajabeen, a lovely mint and black pepper smoothie.

That said, part of AFGI’s appeal for this project was for us to document what it’s like to visit Pakistan and hopefully let people know that it’s not a hazardous place so we traveled everywhere in an armored car with armed security. And entering any mall, hotel, or fancy restaurant in Karachi required passing through a metal detector like at an airport, only there were two dudes with shotguns making sure your keys and loose change weren’t still in your pockets. I appreciate their concern for my safety, but I’d honestly consider visiting again with much less hardware.

Karachi and Hala/Matiari in relation to the rest of Pakistan. Image via Google

Most of our time in the country was spent at AFGI’s facilities in Karachi. We toured seven separate factories, and I’ve gotta say, the conditions were better than in many factories I’ve seen in the western world. Many of them were air conditioned, there were regularly scheduled breaks, people wore the proper protective equipment, and men and women worked alongside each other. AFGI even had several women executives–more than I’ve seen in most American brands!

The true highlight of the trip though was visiting Interior Sindh to see our bandanas come to life. Our first stop was the village of Hala, where our fabric was woven. This family-run mill houses only a dozen shuttle looms from the early twentieth century in a space about the size of a strip mall storefront.

The plainweave selvedge fabric is similar to the kind typically used in Ajraks.

From there, we went to Matiari for the printing and dyeing. Matiari is a walled village established in the early 1400s. Abdullah Dada met us outside. They had laid down a trail of flour along the path we needed to take through these cramped alleyways to reach the Ajrak studio on the other end of town (see between the pipes on the left side of Abdullah Dada’s feet below).

Visiting the Ajrak studio will be something I’ll remember for the rest of my life. The studio itself is almost like a ranch, with goats and water buffalo relaxing in an open courtyard and a half dozen Ajrak makers sitting cross-legged inside, stamp-tapping out a variety of patterns.

Our bandana was the main project of the day and we spent several hours reviewing samples and learning the different stages of the Ajrak process. They even let me dye a bandana and get my fingernails blue for the next month.

The printing and dyeing process for our bandanas is the same that Ajrak makers have followed for thousands of years. I even met the camel that donated the poop!

The printed and dyed bandanas arrive back at AFGI in large sheets of eight for cutting and sewing. AFGI’s crack sample sewing team lead by the master tailor, Naveed Khattri. Three cuts and three hems (the selvedge is on the fourth edge), and the bandana is ready.

We went through several iterations, making sure all of our pattern showed up clearly in the final product. This required a long game of telephone between ourselves and the printers in Matiari, but after about a dozen samples, we had our bandana.

Packaging

We have admittedly large shoes to fill after last year’s space exploit with PF Flyers, but I’m very pleased with how the bandanas are presented. The “party favor” this time around is a wooden bandana holder, made from the same Indicus arabica tree that’s used for the carved Ajrak blocks. It’s smooth on the outside and rough on the inside so it can grip the fabric.

Both are then folded up along the edges of each facet of the design, so that opening it up shows the result of each block print. The bandana and holder are then put in a recycled paper box and tied off with indigo warp yarns that were dyed and spun at AFGI (careful, they crock!).

CO-OP Rules

1. All source materials must be minimally processed, raw, and undistressed.

The processes used in making this bandana date back over three thousand years, it’s about as raw as it gets.

2. The source and contents of all materials and hardware must be made explicit.

The fabric was woven at a small family weaving facility in Hala, Pakistan; the bandanas were printed at an artisanal Ajrak workshop in nearby Matiari; and the cutting and sewing happened at AFGI’s facility in Karachi, Pakistan.

3. Design, sourcing, and production decisions must be made to produce the best possible product. Cost considerations must be secondary.

Henry and I spent about four years developing this bandana and we made significantly more samples and test bandanas than the actual number we decided to release. AFGI very generously subsidized the cost of this project because if we were to account for all the man hours spent developing, sampling, and producing this piece and tried to make it back at margin, each bandana would likely cost over a thousand dollars.

4. Products must be wholly original to collaborating brands in design, name, and material.

The art, fabric, and even blocks were developed entirely originally for this project. This is also the first product that AFGI has ever put their name on and sold to the public so it is entirely original.

5. Products must represent the joint decisions of Heddels and the collaborating brand. The process will be a true collaboration, not a private label or made to order good.

This project had a few players: me, Milan, Henry and the AFGI team, and Abdullah Dada and the Ajrak makers. Everyone played a significant role and had input in the final product.

6. Products must be limited, numbered, one-time-only releases. Collaborating brands may continue to use a CO-OP developed design but never the exact makeup as the CO-OP product.

The production process in Matiari is slow and deliberate. This is going to be a several hundred piece release but we are doing it in stages. The first 50 pieces of the run are going to be released now and we plan on restocking as further bandanas are produced later this year. Although it did take about 18 months to make this first batch so don’t hold your breath.

7. No more than 500 and no less than 5 units of a CO-OP product will be produced.

50 units have been produced of the planned several hundred.

8. Heddels must physically visit and document where the product is made and the people who make it.

Watch the video if you don’t take my word for it!

9. Every individual involved in the creation of the product must be credited by name.

Heddels team on this project is myself, Nick Coe, and Ryan Lindow. AFGI’s team on this project included Hasan Javed, Henry Wong, Mehak Afroz, Hammad Channa, Samsheer Mushtaq, Aleesha Hussain, Majid Ali, Naveed Khattri, and Muhammad Sharif. The Ajrak makers in Matiari included Abdullah Dada, Abdus Salam and the block carving was done by Kashif. Original artwork created by Milan DelVecchio.

10. Products cannot be sold until the product is on hand and paid for by Heddels. No crowd-funding, no pre-sales, no net 30.

They are imported, in stock, and ready to ship.

11. A product’s retail price must not exceed twice the unit cost of the creation of the product.

As I mentioned above, based on the work that went into these bandanas, $44 is an absolute bargain. What we’re selling them for barely covers a one-way ticket to Karachi.

12. Products must be accompanied by an article documenting its design, sourcing, and production.

There’s a video too! Check the top of the page if you missed it.

13. Products must be accompanied by a relevant souvenir, aka the “party favor”.

We included a bandana holder ring made from the same wood as the blocks are carved from.

14. All sales are final except in the event of a manufacturing defect.

This is a handmade product in nearly every sense and yes, it’s supposed to smell faintly of the zoo.

15. Products must be sold by Heddels.

All bandanas will be sold via our webstore.

Availability

Bandanas will be available online at the Heddels Shop on Monday, February 25 at noon ET and sold on a first come, first served basis.