In September, 1945, Kenzuke Ishizu was living an uneasy existence, locked in a former Japanese naval library in Tianjin, China. Japan had unconditionally surrendered to allied forces and as a naval attaché, he was understandably concerned about reprisals by Chinese Nationalist forces.

An unerring dandy, he’d been a part of the so-called “mobo” movement (Modern Boy) in the 1920s back in Japan, that had taken the Meiji Era’s westernization efforts to heart, having beautiful suits made, getting his hair cut short, and even racing motorcycles in his free time. His salvation came when the U.S. 1st Marine division arrived and recruited him as a translator.

Kenzuke Ishizu. Image via Grailed.

A Marine named O’Brien busted Ishizu out of his self-imposed prison and their cooperation/collaboration involved O’Brien reminiscing about a university called Princeton and something called “The Ivy League.”

Identity, Trauma, and the West

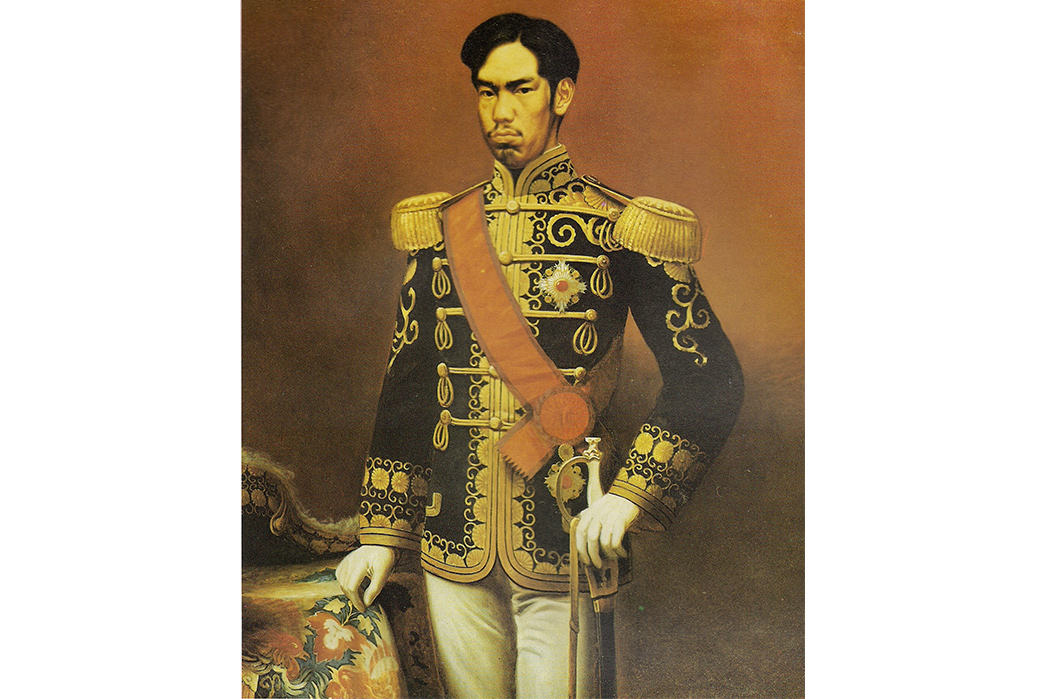

Emperor Meiji in Western dress, image via Wikipedia, painted by Takahachi Yuichi

This first mention of the fabled Ivy League would evolve into a full-fledged fashion movement in Japan. W. David Marx, in his book Ametora, which provides much of the substance of this article, calls Japan a “Country without Style,” but a more accurate statement would be that Japan was a country without “Western Style” and was desperately in search of identity.

In the Meiji Era at the turn of the century, Japan had aggressively adopted Western styles and practices in hopes that this would stem the tide of Western aggression and imperialism… and for the most part, this was successful.

From the time Japan opened its doors to international visitors, Western powers lauded Japan for its tidiness and seemingly civilized ways. Statements like these were, of course, more an inadvertent indictment of the racist and Eurocentric ways that western colonizers viewed the major Asian players. Japan’s apparent cohesion to European standards of life briefly granted the island nation a reprieve from the Anglo-American colonial oppression that beset China and South-East Asia in the same era.

Colonialism, But Make it Fashion

In the early 1900s, to Westernize was to survive. It was the only way to be taken seriously by the major Western powers and prevent a total takeover of your country. But Westernization wasn’t all colonialism and cultural warfare, sometimes it was fun!

Mobo and Moga (Modern Boys and Modern Girls) sprang up in this era. They eagerly embraced the fun, consumer aspects of Western culture. The boys wore their hair slicked back and donned wide-leg “trumpet pants” like those seen above, while the girls adopted silky, boyish skirts—much like the flappers across the Pacific. Kenzuke Ishizu, the man from the naval library, grew up in this dandified era and eagerly embraced the new style-conscious youth culture. For him, as a schoolboy, the Meiji Era had meant lots of rigid structure and scratchy wool uniforms; i.e. the formal, militant aspects of western culture, but what he really wanted was a three-piece suit.

Boy did he get suits. His work took him to Tianjin, where he worked in a clothing store and flitted about among a class of Western expatriates, and in so doing, escaped the worse wartime stresses back home in Japan. His half-hearted contribution to the war effort would remain a source of guilt for quite some time. After meeting and working with the marines, Ishizu was sent back to Japan, forced to abandon his wardrobe and personal fortune. The lean times were upon him.

Long Road to Recovery and to Ivy Style

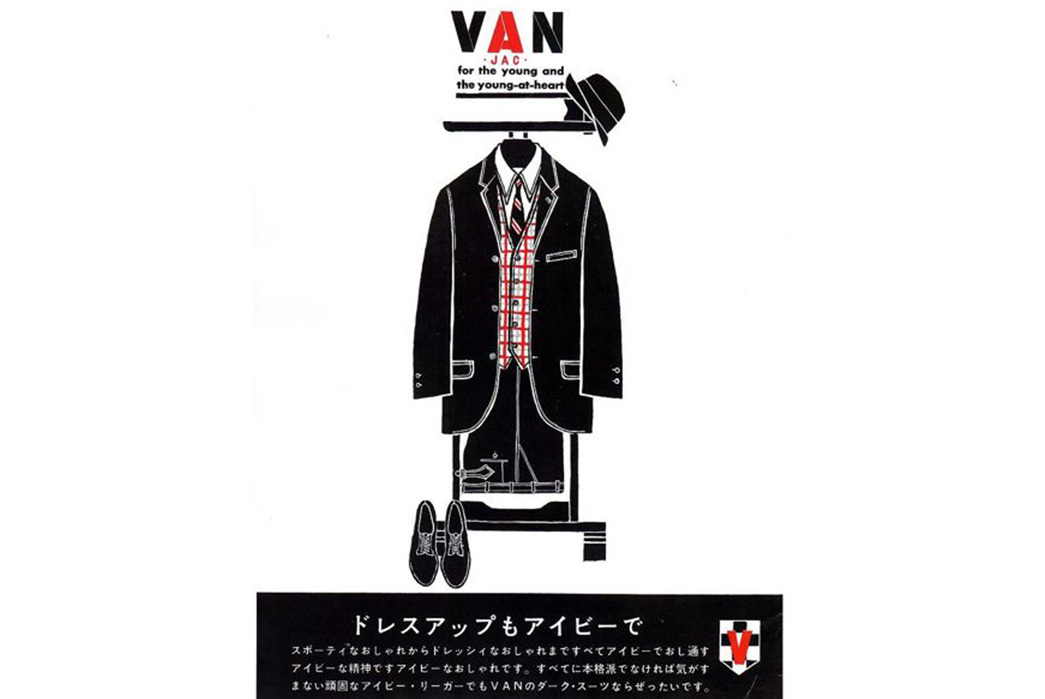

Van Jacket. Image via Van Site.

For a more in-depth look at Japan’s recovery after WWII, you most certainly need to read Marx’s book; but for our purposes, we’ll dilute this period to its most relevant points.

The American occupation of Japan brought the newly-defeated and destitute Japanese people into contact with the American aggressors that their propaganda had warned them about. The only catch was the Americans weren’t quite the animals they’d been portrayed as. They were still invaders, but for the most part, they were able to win hearts and minds and stun the malnourished population with their size and apparent affluence. With an economic recovery slow in coming, even the most objectionable displays of American wealth drew an almost bemused respect from the beleaguered Japanese.

Ishizu, with his background in clothing and familiarity with American fashion, was counting on a renewed interest in fashion – especially American style. Though a risky gamble in these shaky days, he began turning out high-quality garments, hoping a market would emerge. It did.

Ishizu opened his first store at about the time that the Korean War began to revive Japan’s economy. Japanese manufacturing was the lifeblood of the war effort, and although nothing was magically solved in Japan, people at least weren’t hungry anymore and there started to be enough spending money to buy clothes. But Ishizu’s business model was in jeopardy, he sold ready-to-wear suits and sport coats, which almost no one wanted. Even though a tailor-made suit could cost up to a month’s salary, most people looked down on off-the-rack clothing.

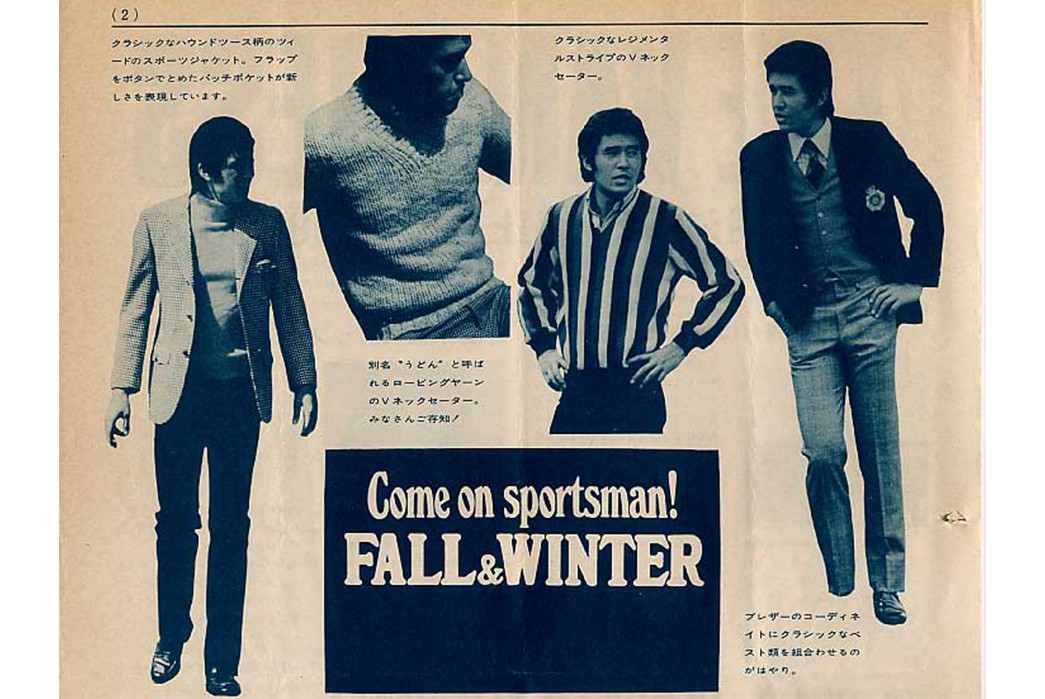

Van Jacket, Men’s Club, and Ivy

Image via Van.

Kensuke Ishizu coined a new name for his brand, Van Jacket, and immediately began pushing hard for stylized American fashions – most of which were pulled from Hollywood movies. But style in Japan was going nowhere until designers could convince men to get into “fashion.”

Men at the time, much as they are now, were afraid to make bold choices in their wardrobes. Marx cites a common refrain among businessmen’s wives at the time; extreme frustration with their husband’s drab business wardrobes, even at fancy events. Intentionality in style makes one vulnerable to criticism and Japanese men in the early 1950s needed to be coaxed into adopting clothes that went against the grain – even if they were still just suits.

Men’s Club Magazine. Image via Pinterest.

Japan’s first real men’s fashion publication hit the newsstands in the mid 1950s, but it wasn’t until Ishizu joined the editorial team and changed the name to Men’s Club that things really took off. The magazine’s goal was to inculcate a fashion sensibility in their readership that would enhance Japanese style – but also to help sell brands closely tied to the publication – brands like Van.

Van needed to find a look that embodied the brand’s values, but wouldn’t scare off conservative dressers. The heavy Hollywood overtones of the magazine gave way to styles reminiscent of silver screen gangsters, and the delinquent look wasn’t in yet. On a trip to the states, Ishizu visited Princeton on a whim, remembering that phrase “Ivy League,” and found a look that would satisfy everyone. The slim suits and loafers of the Ivy League students weren’t so gaudy to suggest effeminacy and they were functional and ready-to-wear. Best of all, there was a chicness to how these students wore their clothes until they were in tatters. It was a look that pushed the envelope without alienating anyone.

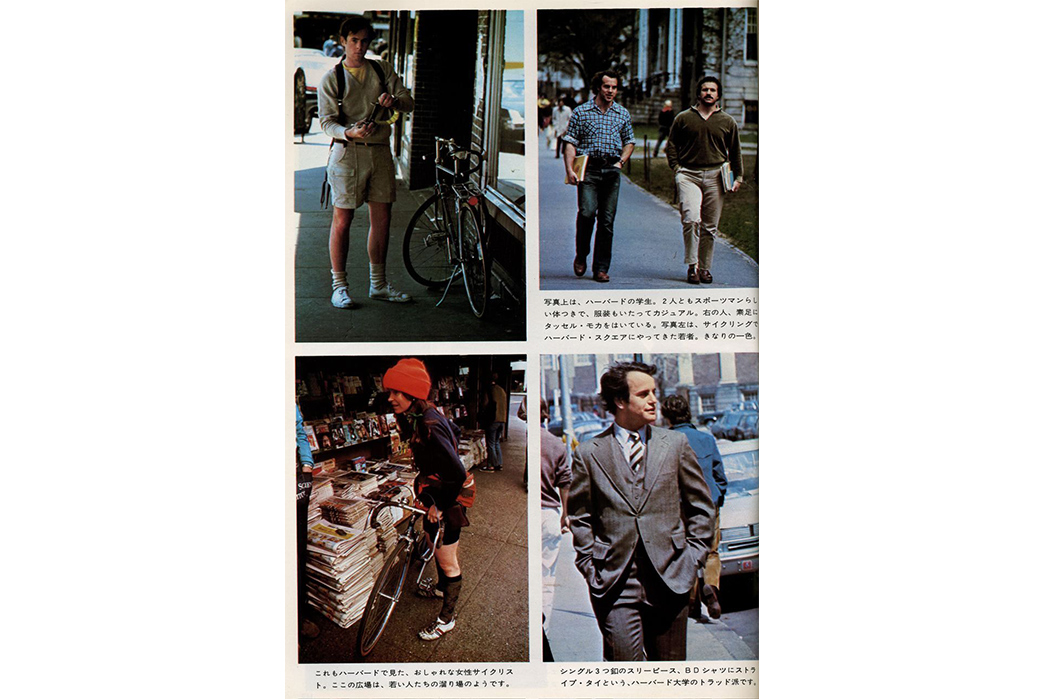

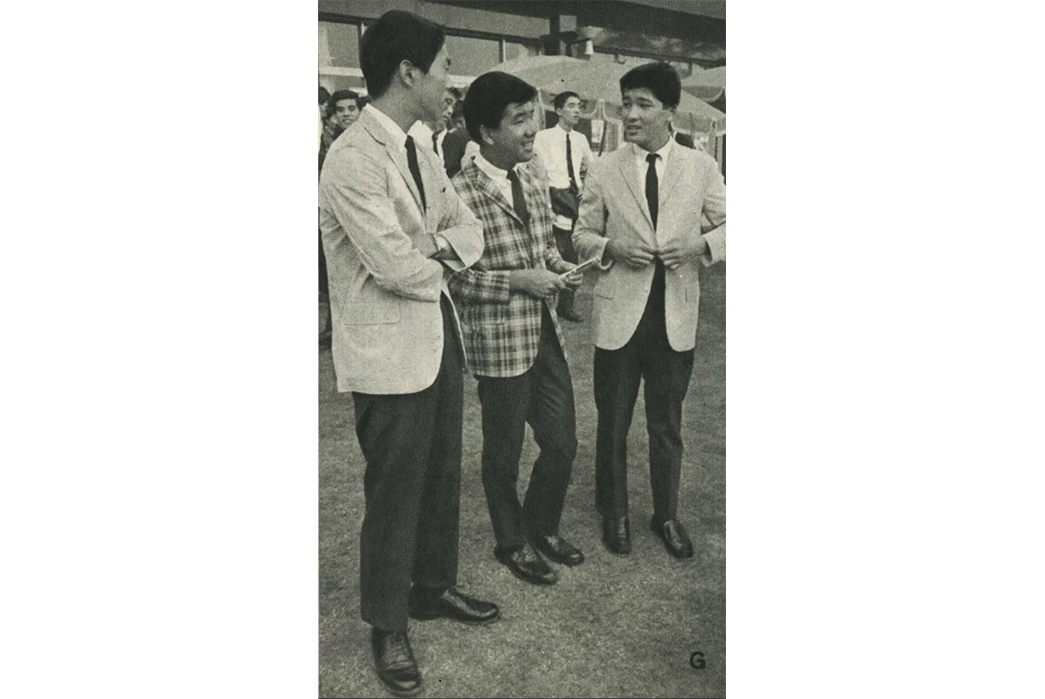

Ivy Leaguers. Image via Ametora.

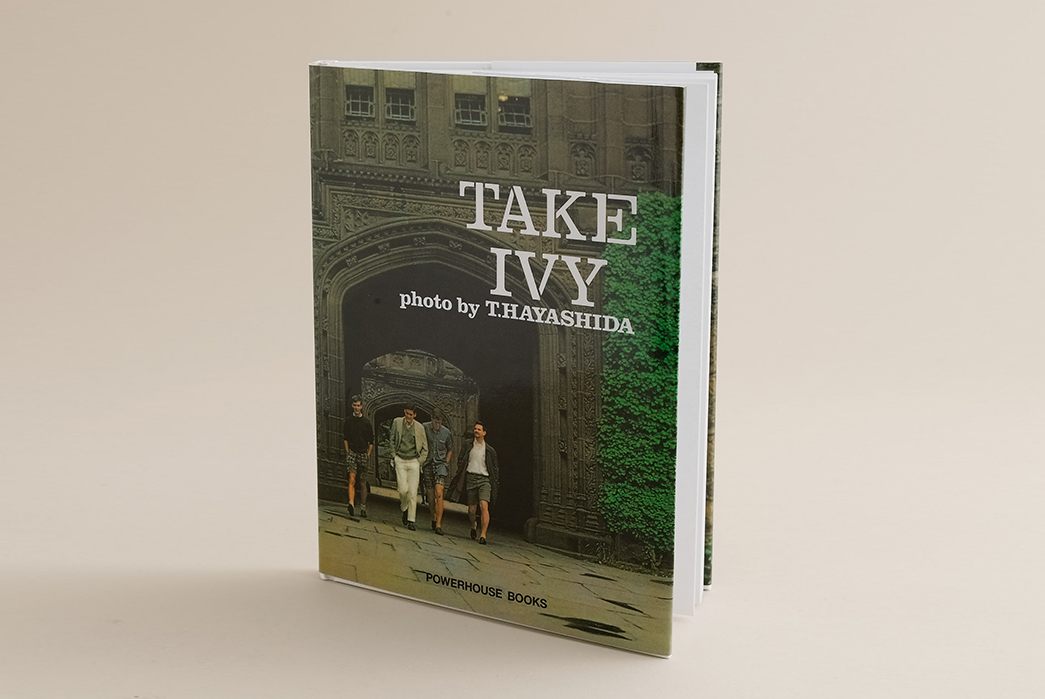

As Ivy style began to proliferate in Japan, a process that again, is best handled in Ametora, the concept began to feel empty. No longer were the guys in the slim Brooks Brothers knockoff suits necessarily experts in Ivy and men’s style, they might just be hangers-on detecting a cool fad. Ishizu green-lit an exorbitantly expensive trip to the East Coast to get some research on the actual schools of the Ivy League. And thus, Take Ivy was born.

Take Ivy

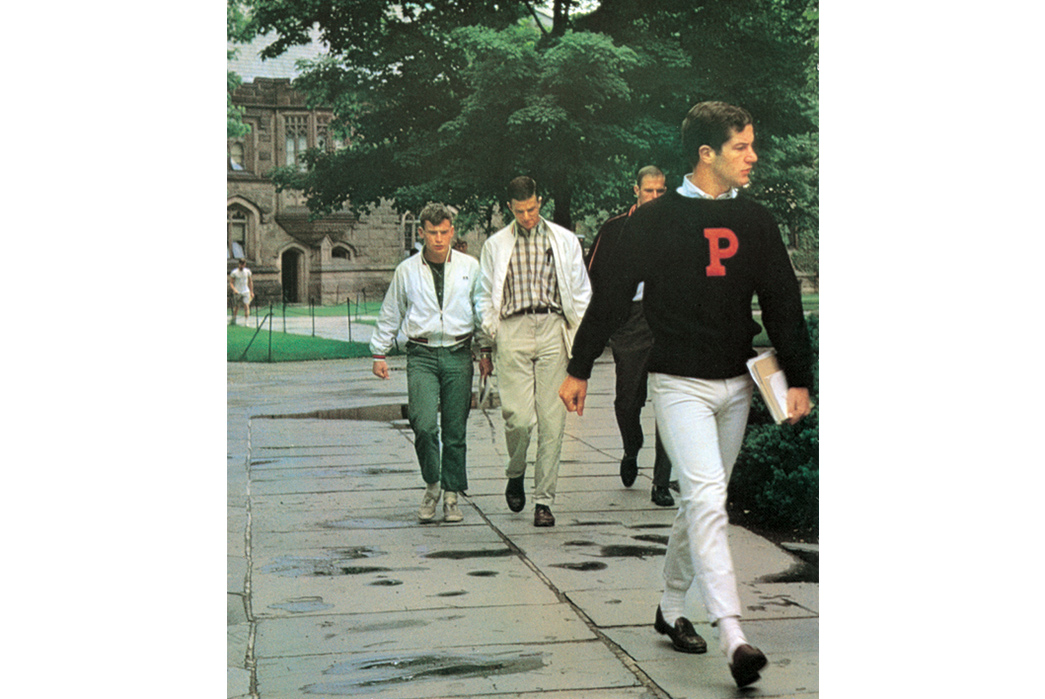

Image via Take Ivy.

The eight-person team arrived in the U.S. in 1965 and were stunned by the dissonance between real Ivy league style and the Japanese understanding of Ivy. The original Ivy style was by now long gone, students in the mid 60s didn’t carry attaché cases or wear saddle shoes. The resplendent sartorial formality of Japan’s Ivy was nowhere to be seen. The crew was dismayed that no students wore the three-piece suits that were supposed to be the de facto Ivy uniform.

This dismay doesn’t read anywhere in the finished book and the final images used feel like the first steps toward the Japanese understanding of fashion that we have today in our wonderful niche. Hard-wearing basics that start sophisticated but grow ever more chic with wear.

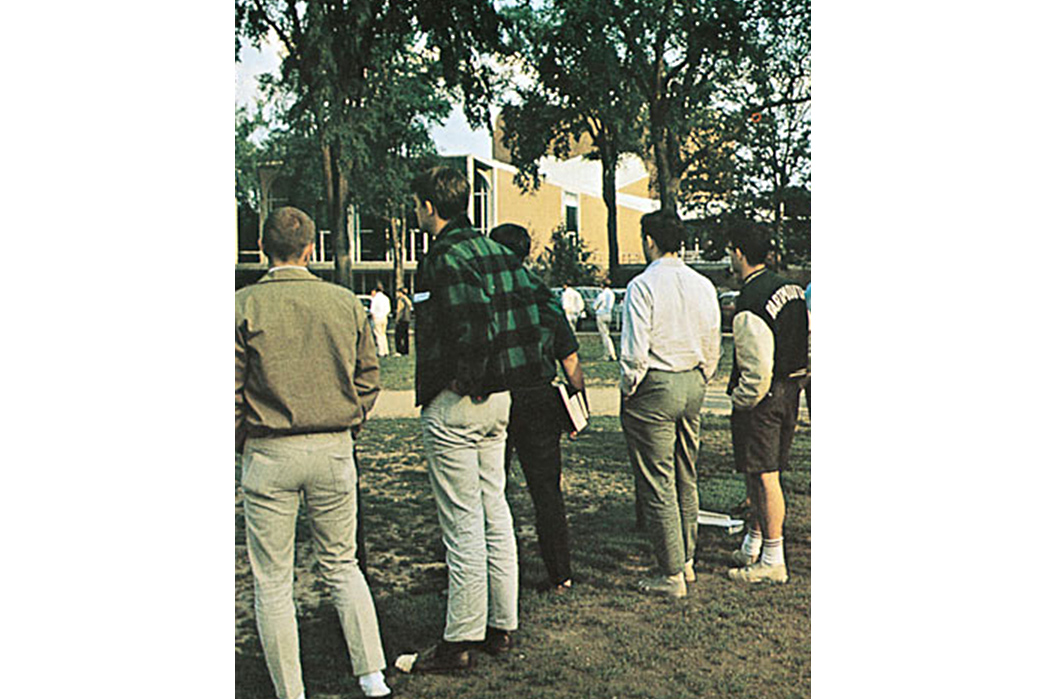

Image via Take Ivy.

The finished product feels less like a lookbook and more like a sociological study. The final portion of the book is entirely devoted to summarizing those indelible elements of Ivy style and giving definitions for various must-have ivy pieces. Of which include twelve ties and two suits, at the very least. Other sections are devoted to explaining the differences between the major Ivy League universities and the rules and fanbases of the big campus sports. The book even goes on to explain the various neighborhoods worth knowing about, examples end up including Madison Avenue and the shops around Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Take Ivy is an invaluable resource and a must-have book in your collection. Its tone captures the simultaneous awe and disbelief of its creators upon realizing the world as they had constructed it doesn’t really exist. Back home, brands like Van had fought tooth and nail to find manufacturers to meet their exacting standards of “American design,” but it upon arriving on Harvard and Princeton’s campuses, it was no longer clear that those design motifs were accurate or even relevant.

In a pre-Internet information vacuum, Japanese designers furthered a genre of Americana that was on the wane in the era of counterculture and the Vietnam War. Making Take Ivy challenged its photographers and writers by showing them that the style-conscious utopia they espoused and emulated maybe never existed. There is no bitterness, in Take Ivy, however; only charming blurbs that summarize those ineffable elements of Ivy-ness for an eager, newly style-loving country.