By the mid-1920s, just about every American who needed a car had one. It had been hard enough to convince Americans that this new-fangled invention was a necessary investment, but now automakers had a new problem. How the hell were they going to sell more cars? How were they going to make any money?

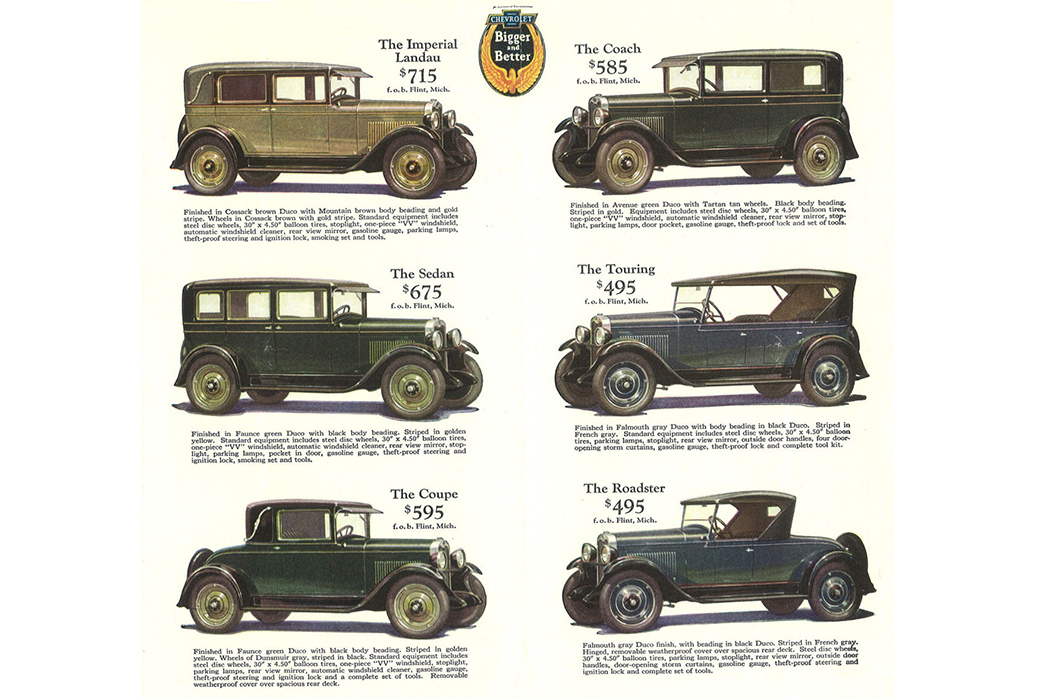

1928 Chevrolet Lineup. Image via GM Inside News.

Henry Ford, despite his white supremacist leanings, had an engineer’s integrity—and didn’t see any point in altering the Model T. It worked well, it came in one color (black) and they lasted as long as their owners maintained them.

His competitors at General Motors, however, didn’t have the same scruples. The head of GM, Alfred Sloan Jr., suggested a campaign that his critics would later label “planned obsolescence,” he would introduce new models each year, in new colors, styles, and with more powerful engines. In so doing, he would create demand for new cars, even before his customers had worn out their first one.

Planned Obsolescence

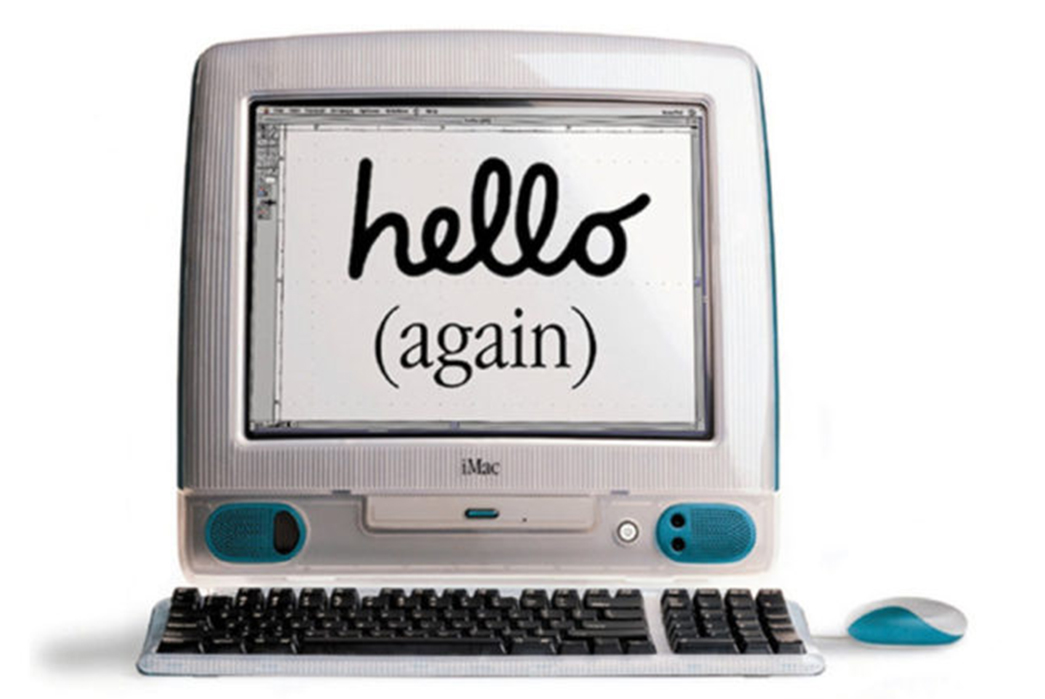

iMac G3. Image via Cult of Mac.

If you’re reading this article on your phone or computer (or even if you’re a psycho and printed it out), you’re familiar to some degree with planned obsolescence. Notice how your devices don’t hold a charge like they used to? Or how your printer cartridges seem to run out of ink before they ought to? That’s planned obsolescence, baby.

Planned or built-in obsolescence is the controversial practice of designing consumer goods with a certain lifespan, typically to promote sales and keep consumers from holding onto a product indefinitely. Obsolescence has many facets, some of which are hard to control, sometimes a product is considered obsolete because it has broken down and no longer operates, but other times, consumers might consider a product obsolete because it’s no longer fashionable. In other cases, manufacturers like Apple, make a product that is nearly impossible to repair, or make repairs so inconvenient and expensive that you’re forced to upgrade to a newer model, even if your previous device had plenty of life.

The Philosophy of Obsolescence

Image via Wikipedia.

Though we attribute the first modern application of planned obsolescence to Alfred Sloan of GM, the philosophy thereof was developed by another man: Bernard London. London’s 1932 pamphlet, Ending The Depression Through Obsolescence, espoused the theory that creating products with an artificially shortened lifespan could boost the economy and lift the nation out of the Great Depression. He explains,

In a word, people generally, in a frightened and hysterical mood, are using everything that they own longer than was their custom before the depression. In the earlier period of prosperity, the American people did not wait until the last possible bit of use had been extracted from every commodity. They replaced old articles with new for reasons of fashion and up-to-dateness. They gave up old homes and old automobiles long before they were worn out, merely because they were obsolete. All business, transportation, and labor had adjusted themselves to the prevailing habits of the American people. Perhaps, prior to the panic, people were too extravagant; if so, they have now gone to the other extreme and have become retrenchment-mad.

London goes on to suggest a government program whereby old goods that had been deemed “useless” would be bought up by the government and destroyed so that consumers could go out and buy newer versions of the same products and stimulate the economy and get people back to work in manufacturing jobs (*cough cough* Cash for Clunkers *cough cough*) .

Although London’s scheme was, by all accounts, cockamamy (I mean, if Americans don’t want universal healthcare, I can’t imagine they’d love the government coming to their homes to destroy their old furniture), the central theme of forcing consumers to spend money to stimulate the economy, remains a central tenet of the pro-planned obsolescence argument. But one place where London takes a rather progressive tack is by insisting that manufacturers declare the planned lifespan of their goods before a customer makes their purchase—a battle that is currently raging today.

Planned Obsolescence in our Daily Lives

Currently obsolete parade of iPhones. Image via The Verge.

The handiest example of planned obsolescence is the one we probably use the most, the iPhone. In December 2017, a lawsuit was filed against Apple for purposefully slowing down older iPhone models when newer versions came out. Despite a response by the company, claiming that these slowdowns were to protect the phone’s battery health, a total of 59 class-action lawsuits were filed within the following year. Apple claims this serves a greater purpose, but the suspicious throttling of battery-power, combined with tamper-resistant pentalobe screws, and non-user replaceable batteries makes a skeptic wonder exactly what good-faith company would put in so much work to prevent access to the battery. After all, it’s the part of the phone most prone to failure.

There is another side to PO, of course. There are critics who believe that planned obsolescence is not the manufacturer’s fault; rather it can all be traced back to greedy consumers. With iPhone users at market saturation, Apple has employed a similar model to GM in the 1920s. Even without alleged slowdowns and service issues, a great number of iPhone users will simply upgrade to a newer model because of its improved features and the mere fact that it’s the newest thing.

There are, of course, more insidious examples of planned obsolescence. A 2007 court case, Blennis vs. Hewlett-Packard found HP guilty of installing chips into printer cartridges that would shut down the cartridge after an undisclosed amount of time, even if there was still ink left inside. Frequently, home appliances like fridges and washers are made with one shoddy and expensive component that can only last so long but is so expensive to repair that it’s often more cost-effective to simply buy an entirely new product.

Planned Obsolescence in Fashion

Image via themds.

Unfortunately, trend is a huge factor in obsolescence. It’s easy, with modern fast fashion cycles to convince consumers that the pieces they have are suddenly out of style. This is reinforced by brands that make pieces designed to barely last a season, part of which is to ensure a returning customer, but also to keep prices down.

Unlike washers and cell phones, clothes aren’t necessarily manufactured with an Achilles’ heel, the repair of which could render the whole piece unusable, but trends like pre-distressing clothing means consumers buy a product with more than half of its life already gone before the first wear. To a modern audience, raw denim and loop wheeled t-shirts may seem over-engineered, mostly because the products they’re used to have been stone-washed and shredded to within an inch of their life.

The master of well worn denim Ruedi Karrer. Image via the Jeansmuseum.

The philosophy that obsolescence promotes consumption can be disproved by our readership at Heddels. If you trust consumers and offer them the highest-quality, longest-lasting products on the market, they’ll likely come back. How many of us bought our first pair of raw denim jeans intending to wear that one pair for years, only to end up with an enormous collection?

By condescending to consumers, as many brands do, and treating them as flighty and unable to commit to high-end, long-lifespan products, planned obsolescence ensures that appalling amounts of clothing ends up in landfills… the real dark side of this is waste and pollution.

Avoiding Planned Obsolescence

A mountain of tech waste. Image via The Australian.

Though planned obsolescence is ubiquitous in our current consumer economy, it isn’t always easy to prove that your appliance’s slow decline in function isn’t just natural entropy. Beyond that, companies do a pretty good job of covering their tracks, or at least maintain a degree of plausible deniability that can make it hard to pin anything on them. For example, while some people might feel that Apple is purposefully slowing down their phones, it could very well be that the updates designed for a better-made piece of hardware will just naturally function slower on an older device.

The discussion on PO in the U.S. is very back-and-forth, with people taking turns denying and espousing this theory, but elsewhere in the world, greater steps are being taken to combat this issue. In France, in 2015, a law was passed mandating that manufacturers declare the intended lifespan of their products and for how long spare parts will be made. After all, a consumer ought to have a right to choose the product that will last longest or best fit their needs. And the next year, in 2016, a new law was added to the books that effectively provided a two-year warranty to all appliances. If a device fails you within two years, the manufacture must replace it.

Unfortunately, those of us outside the European Union have no legal recourse when it comes to obsolescence unless you want to hire a lawyer and take on Apple yourself. The Consumer Product Safety Commission has the right to pass durability standards if it wishes to do so but it doesn’t seem to want to. As American consumers, we are trapped in a rather predatory environment. Big business says that flimsy, short-lifespan products promote growth and advancement and that our constant buying helps our economy blah blah blah. Unless the government intercedes and passes durability standards or mandatory warranties like those in the EU, companies have no impetus to improve products nor to disclose how long they will last.

You probably need a phone and you probably need a washer; but until some dark horse company emerges on the market and forces the competition to up the ante, you’re going to have to buy with your gut. Read reviews, do your research, hope for the best, and know that anything we feature here on Heddels is something that we think is made to last an awfully long time.