“Don’t throw your boots away” is Felix Jouanneau’s maxim. Officially, he’s been in the business of telling people this since 2017, but he was fascinated by footwear long before then. “When I was young I would watch quite a lot of western movies with my dad, and they always had a good shot of the boot going into the stirrup as the cowboy mounted his horse,” Jouanneau says.

So, his bespoke bootmaking vocation is down to his pop, then? “My father also owns just a few good pairs of shoes that he would get repaired. They lasted him most of his life through looking after them very well,” he explains. “The moment that really sealed the deal was during a trip around Tuscany. I walked past a shoemaker’s in Florence and saw a man working on a pair of shoes, he had some lasts behind him; I did not enter the shop but it was inspiring enough for me to go back to England and start a career in shoemaking.”

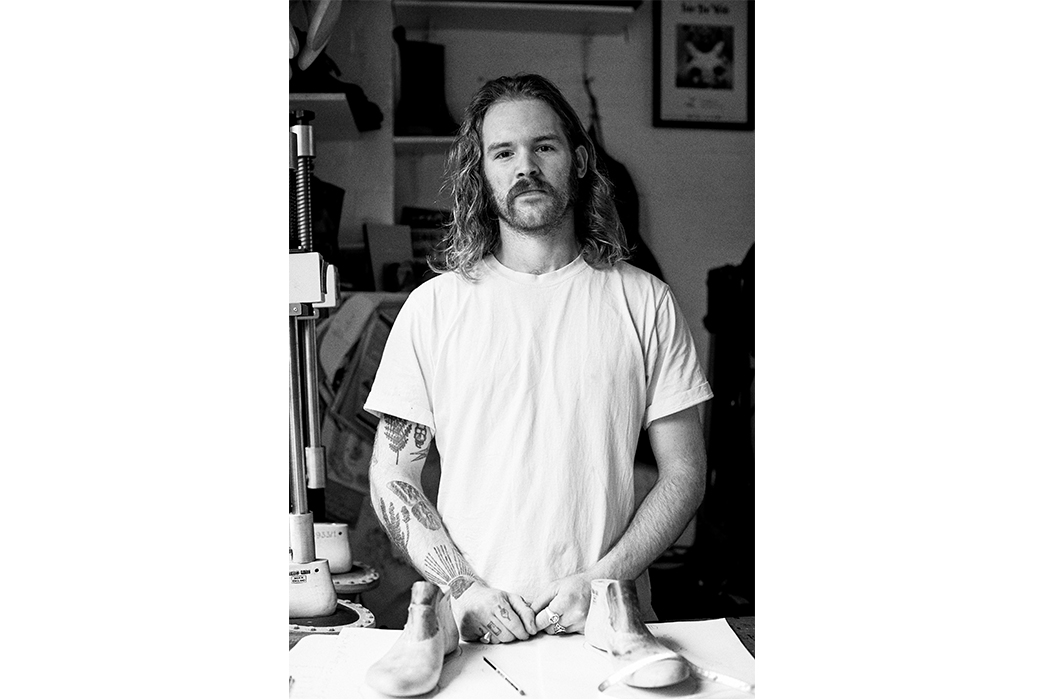

On the day I visit him in his studio in Shoreditch, London, summer is drawing to a close but the back door is propped open, filling the room with fresh air, while Link Wray & His Ray Men’s Rumble sounds from the speakers. Felix’s workshop is a treasure trove for anyone with an appreciation for crafts and tools, or the way things were made long before mass consumerism engulfed society. The space he shares with a fellow shoemaker is nestled in a row of listed brick buildings dating back to 1899. It’s a throwback filled with old machines, timeworn boots awaiting repairs, shoe lasts strung from the ceiling, snakeskins and retro motorcycle posters.

Image via James Grant

Since founding his bespoke bootmaking service two years ago, things have been steadily on-the-up, and Felix already counts a partnership with jewelry smith The Great Frog London and an appearance at the very first Assembly Chopper Show, a vintage motorcycle rally, as two of his biggest successes to date. He speaks excitedly of recent creations, imagining every pair of boots as a collaboration between himself and the customer. When he goes on to detail his last-making practice, it’s apparent how much care is involved in achieving a perfect fit unique to each wearer.

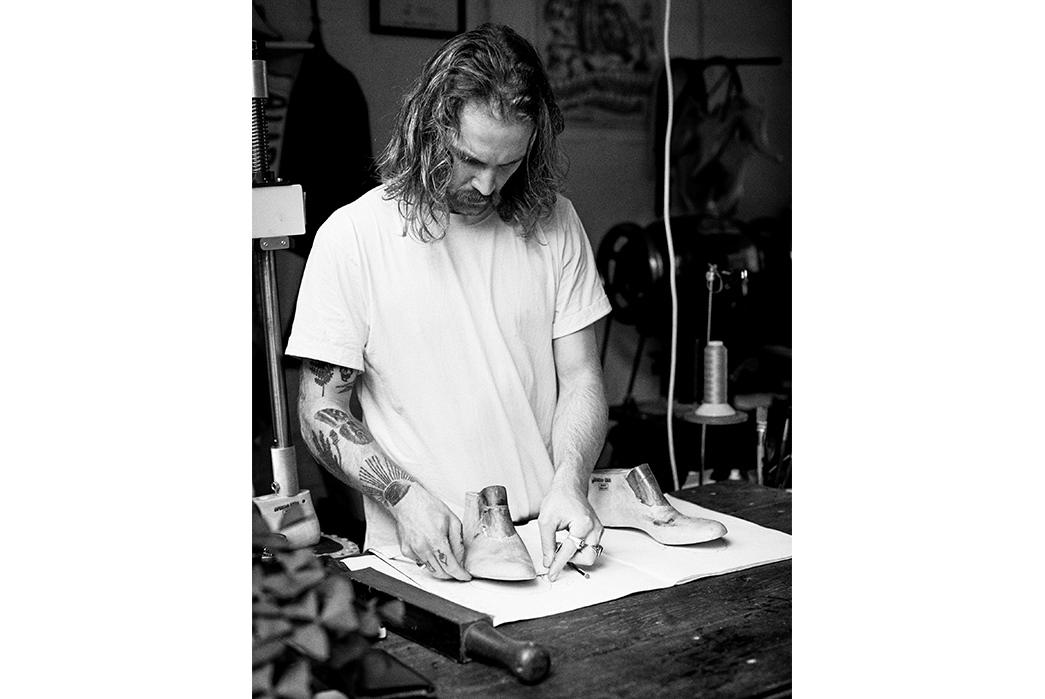

Nowadays, he spends roughly six days a week in the Shoreditch workshop, fixing up worn shoes or making pairs from scratch, which is an incredibly labor-intensive process that takes, on average, ten solid days of work. He describes:

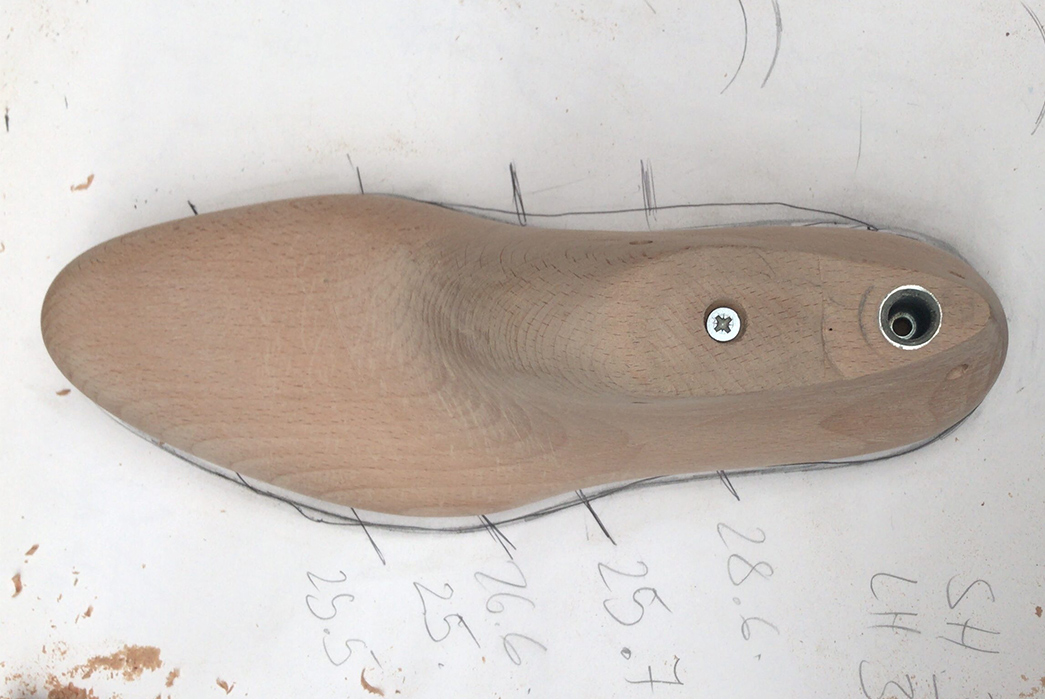

It starts with the customer fitting, and I take key measurements of the foot and leg to be able to build them a boot that will fit them perfectly. I start carving a beech-wood last into the shape of the boot and make sure that my measurements and shape align with the shape I am carving. Great last-making is a perfect blend of shape and foot measurements. Once this vital process is done, I make the pattern which involves taking the 3D shape of the last into 2D, to draw each individual piece that makes up the boot. The pattern pieces are cut out of fine quality leather which has been determined by myself and the client.

All the pieces of the leather that will meet other panels are hand skived with my sharp Japanese knife so that each one blends seamlessly into the other without making the boot look too bulky. The insole and stiffeners are then prepared from oak bark-tanned leather sourced from one of the oldest tanneries in Devon. The insole will hold all the boot together and the stiffeners will provide support on the heel and toe.

The next step is the lasting process where the leather upper is stretched around the last to take its shape, inserting the stiffeners between the lining and the upper. The boot is usually left on the last for at least a week to ensure the leather better retains the form.

Then comes one of the most important processes, which is hand-stitching the welt. This is a piece of thick vegetable tanned leather that the sole will be stitched onto. The stitches will hold the insole, upper and sole together. This is one of the strongest types of construction and a major benefit is that the boot will be much easier to repair as many times as needed since everything is stitched together. A hand-welted boot is a lifelong product if it’s looked after properly.

Finally, the sole is built and is attached using my Rapid E outsole stitcher. The heels are built and attached with serrated nails. The sole is shaped and finished with beeswax to seal the edges and protect the leather sole from the environments, and voila! Apart from the packaging and sock, you have a finished boot.

Then there are his machines and the quest to find them, an adventure in itself for the bootmaker. Most of the devices are vintage, sourced from manufacturers around the UK or Europe and certainly not always used for the purpose they were originally intended. It wasn’t without exhaustive reading on internet forums and plenty of research that Jouanneau managed to get hold of them, either.

Image via James Grant

Later, over email, I borrow Felix’s expertise for some tips on buying and caring for footwear, “Buy quality not quantity” he insists. “Make sure it’s a hand welted or Goodyear welted construction as it can be repaired a lot easier without damaging the upper. Go for something simple that you will be able to wear with most things.”

And what about keeping them tip-top? “Alternate your boots, do not wear them every single day. From wearing your boots, the leather absorbs a lot of moisture and sweat that stops the material from breathing. The acidity from the moisture usually breaks down the leather and causes it to dry out… this can be avoided by using raw wood shoe trees, which will absorb the excess moisture and help the leather breathe” he advises.

Lastly, some sound guidance on what to do should your shoes get a battering in the rain: “let your boots dry naturally in the event you’d get them soaked. Stuff them with newspaper or shoe trees and don’t put them near the radiator or fire, and finally, just like your skin, make sure you give them moisture such as shoe cream or leather conditioner to avoid them feeling dry and brittle.”

You’ll be looking at a fair wait if you want some work done by Felix because he’s one of the only people in the UK working with such specialist construction skills, plus, word-of-mouth and good old Instagram have ensured he’s not short of clients.

How does he manage to balance entrepreneurship with the creative side of things? “The most difficult part of working as an independent maker is learning that I have to fill in many other roles to make my business succeed. Becoming a great bootmaker is the core of what I do, but I also have to become a great accountant, communicator, marketer and salesman.”

This may be tough, but Jouanneau appreciates the freedom it affords him, both creatively and in terms of quality control. “I develop my own designs and manage my production the way it appeals to me and my beliefs” he explains. “I try to source local products to support the regional industry and try to stay well clear of the wasteful fast-fashion industry. I try to make a product that will last a lifetime, not just a season, and produce things with style and quality rather than with the next trend.”

A final word, then, on what he’s cooking up next, “the near future for Felix Jouanneau is to start developing a made-to-order service aside from the bespoke service, to make a more accessible high-quality product.” He speaks in detail on this subject at his workshop, and with that (and some chat about his fickle Harley Davidson Ironhead), we part ways, leaving us excited to see how things will develop for the bootmaker.

You can find Felix on Instagram or on his website. Felix’s fully bespoke, hand-welted shoes start from £935, and a pair with a machine-stitched Blake construction begins at £666. Prices for repairs start at £120.