Here at Heddels, we throw the term ‘Wabi-Sabi’ around like cranberry sauce on Turkey Day. While we’ve not honed in on this unique Japanese term before, the philosophy it represents is intrinsically linked to one of our main goals—helping you to own things you want to use forever.

If you’ve been stumped by our sweeping use of Wabi-Sabi, this article will give you the lowdown on the term how it links with the products and ideas we champion at Heddels.

What Does Wabi-Sabi Mean?

Image via Pinterest

Wabi-Sabi is “a way of life that appreciates and accepts complexity while at the same time values simplicity,”

-Richard Powell, author of Wabi Sabi Simple.

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi (侘寂) is a world view centered on the acceptance of imperfection.

“Wabi” is said to be defined as “rustic simplicity” or “understated elegance” with a focus on a less-is-more mentality.

“Sabi” is translated to “taking pleasure in the imperfect.”

In our business, the concept of Wabi-Sabi applies in a variety of ways. Faded and damaged denim; fabrics with irregular ‘slubby’ weave—and the world of patina—be that on a well-loved leather wallet or a decades-old cast iron pan.

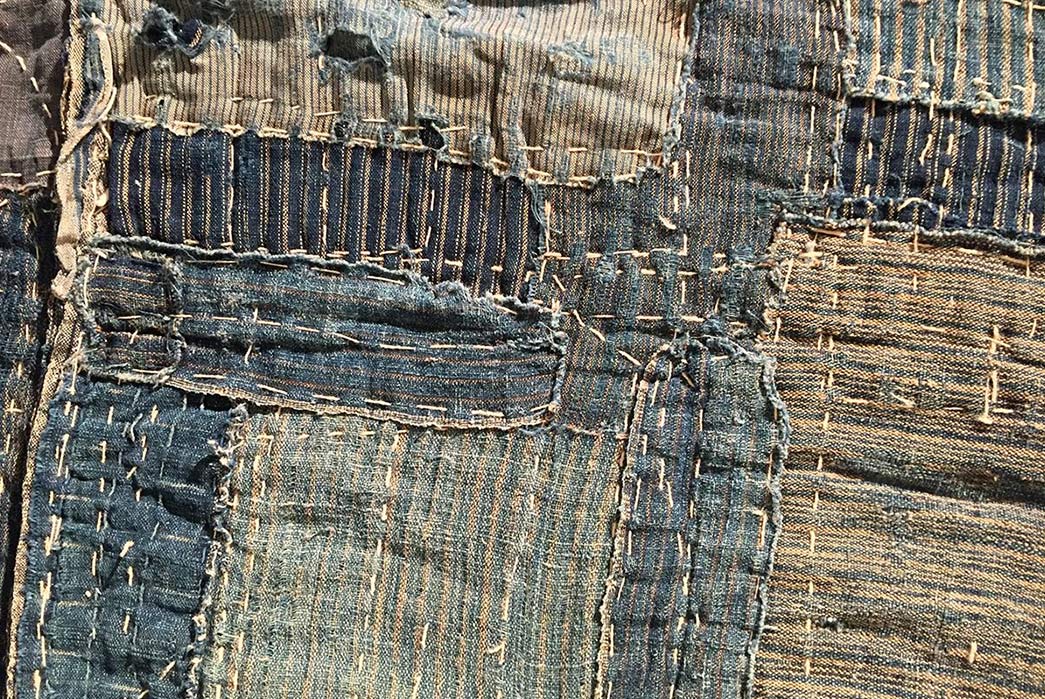

You could argue that our entire Fade Friday series is a perennial appreciation of Wabi-Sabi. To many, a pair of jeans worn to shreds with patches and repairs might seem like something flawed and ready for the trash. Admiring the unique decay of raw denim, fine leather, or any other fabric for that matter, is to practice Wabi-Sabi.

But the concept of Wabi-Sabi doesn’t have to apply to aged products or even physical objects for that matter. Wabi-Sabi can mean admiring the uneven edges of a natural wood coffee table, the worn grooves in an old stone staircase, or appreciating the sound of rainfall while it otherwise causes you a nuisance.

How Did Wabi-Sabi Manifest In Japanese Culture?

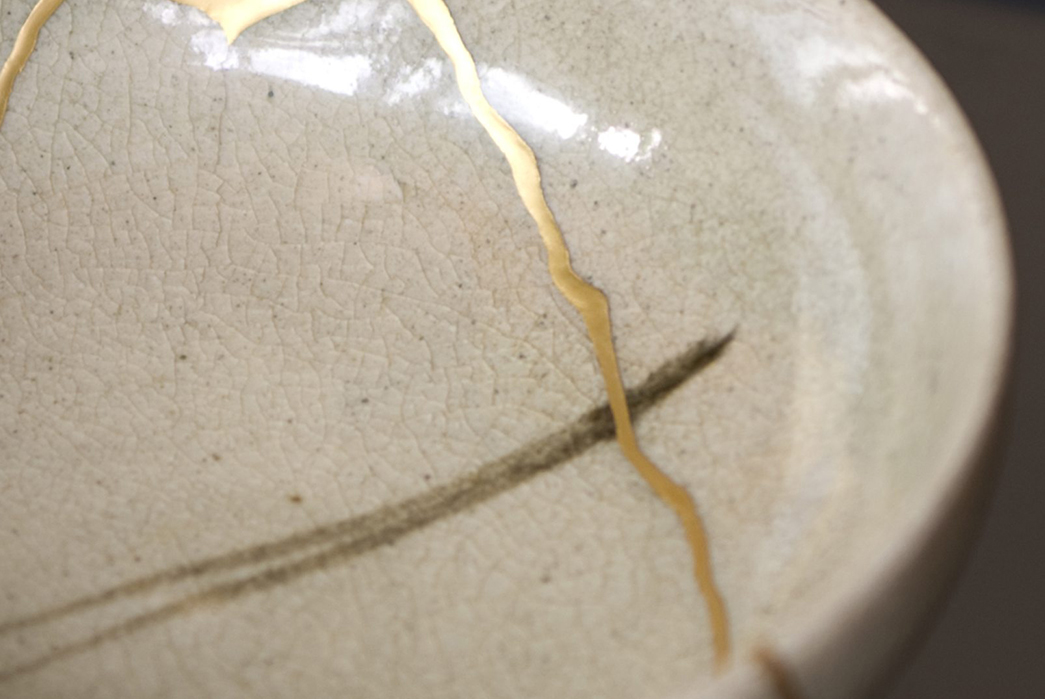

Kintsugi pottery via BBC

Wabi-Sabi has grown as a concept over thousands of years, and its influence is evident in many Japanese craft forms. Kintsugi (translating to “golden joinery”), also known as Kintsukuroi (translating to “golden repair”), is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered precious metals like gold and silver.

As an art form, Kintsugi honors the Wabi-Sabi philosophy by treating damage and repair as part of the history of an object—something to build upon and admire, rather than disguise or dismiss.

Boro and Sashiko are two other examples of how Wabi-Sabi has manifested in Japanese culture. These crafts, both of which are very prevalent in modern fashion and the raw denim scene, differ in their conception, but both channel the concept of Wabi-Sabi in their own unique way.

A sashiko-laden kimono via Tatter

The origins of sashiko are found in the peasantry of ancient Japan. Translating roughly into ‘little stabs’, sashiko was winter work for women from farming or fishing families, who used the technique to extend the life of worn fabrics, mend, and winterize clothing, and embellish everyday items.

But the Japanese grew to appreciate the beauty of these folk textiles and their imperfections.

Traditional boro kimono via Gerrie Congdon

While Sashiko was used often used to embellish otherwise dull working garments, Boro was exclusively born out of necessity. Meaning “ragged” or “tattered,” the boro style was favored by nineteenth and early twentieth-century rural Japanese.

Cotton was not common in Japan until well into the twentieth century, so when a kimono or sleeping futon cover started to run thin in a certain area, the family’s women patched it with a small piece of scrap fabric using sashiko stitching.

These textiles would be passed down through generations, each of whom would add their own pieces of scrap fabric. While the practice of boro was considered shameful for most of Japan’s modern history, it is now seen as a beautiful development in the nation’s cultural development. Its imperfections are now seen as beautiful, charming details, conjured in times of hardship.

How Can We Apply The Wabi-Sabi Concept In Our Everyday Lives?

Sashiko denim repair via Medium

Wabi-Sabi offers a refuge from the modern world’s obsession with perfection—be that aesthetically, financially, or any other aspect of our busy, fleeting lives. The concept teaches us to accept imperfections as meaningful and, in their own way, beautiful. Necessary even.

While it may take a bit of time to employ a Wabi-Sabi outlook in all elements of your life, a good place to start is your belongings. View each new imperfection as a chance to foster a deeper appreciation for that item.

Patch up that hole in the knee of your jeans yourself, knowing that it only symbolizes the use and wear you’ve got out of those jeans. Learn to love that little hot sauce stain on the hem of your jacket, earned eating an oversized burrito in the company of good friends.

Appreciate the frays on the neck of your undershirt, knowing they formed whilst that garment kept you warm on cold days. The list goes on, but the beautifully simple concept of Wabi-Sabi will always remain the same.