We may spend more than our fair share of time and resources trying to emulate classic working-class styles, but it’s all too infrequent that were reflect on the struggles and sacrifices of actual working peoples. Our love of working man’s wear might make us think of laborers, cowboys, miners, and garment workers—but who were those people and what were their lives actually like outside of the clothing they left behind?

Though we adore (and almost fetishize) clothes that have been made in the U.S., that iconic “Made in the U.S.A.” tag in our clothes isn’t the silver bullet to iniquity that we sometimes make it out to be. As evinced in current reporting, most recently by the New York Times on fast fashion giant Fashion Nova, it’s still possible to manufacture stateside while robbing your employees blind.

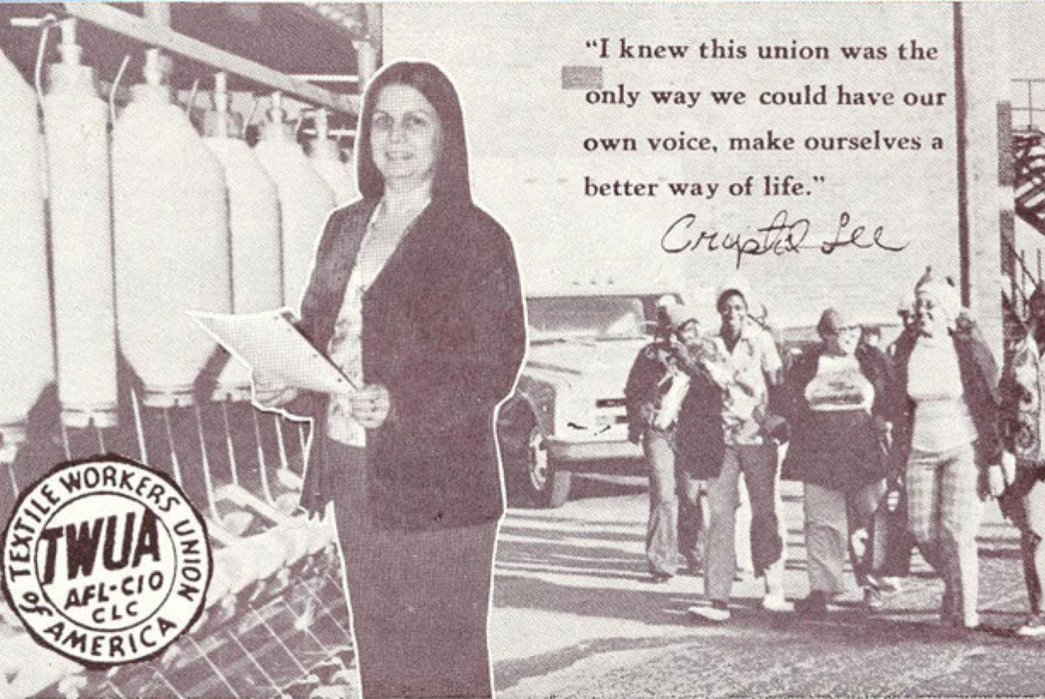

Of course, this is nothing new. Any measure of worker protections that exist in the textile industry and in fashion more generally, are the work of bold pioneers who risked their safety and livelihoods to better the conditions in which they and their fellow laborers worked. We’ve decided to put the spotlight on several such Labor Rights legends and today we pay homage to the incomparable Crystal Lee Sutton, who revolutionized unions in textile mills all throughout the southern United States.

Crystal Lee Sutton

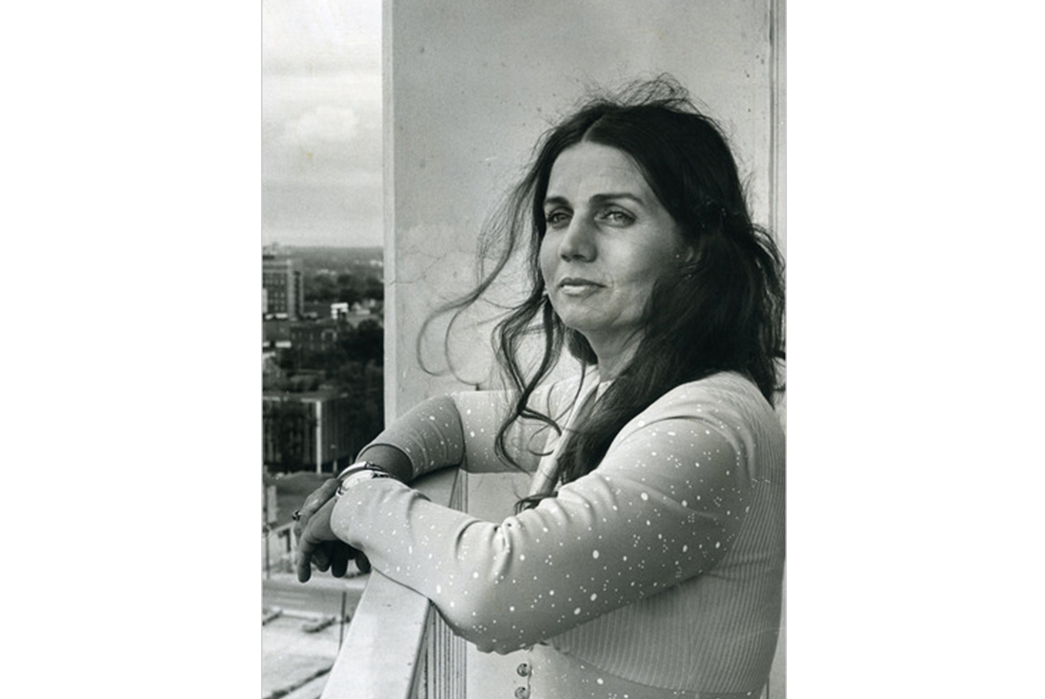

Crystal Lee Sutton. Image via The NY Times.

Crystal Lee Sutton (née Pulley) was born in December 1940 in the town of Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina. Sutton’s family had lived in Roanoke Rapids for generations and they’d all worked in the textile industry. The town was settled on the fall line of the Roanoke River, where a series of falls and rapids could be channelled into water power, power that was used to operate mills.

Mills and their surrounding towns (often owned by the same companies that operated them) were once heralded as a force of progress. Early industrial mills in places like Lowell, Massachusetts offered women of the late 1800s a way out of the home and even educational opportunities and many of the mill owners created towns to house their workforce, often in accordance with their own pseudo-utopian ideals.

These idyllic working towns diminished in progressiveness as the years wore on and by the time Crystal Lee came along, the situation was pretty dire for working people in places like Roanoke Rapids.

Crystal Lee would clash with J.P. Stevens & Co. (now Westpoint Home), the company that owned the factories and homes in which the textile workers spent their days and this clash would be immortalized in the 1979 film, Norma Rae. But her real-life struggles were not as clear-cut or glamorous as those of Sally Fields’ in that Oscar-winning role based on her life.

Southern Textiles

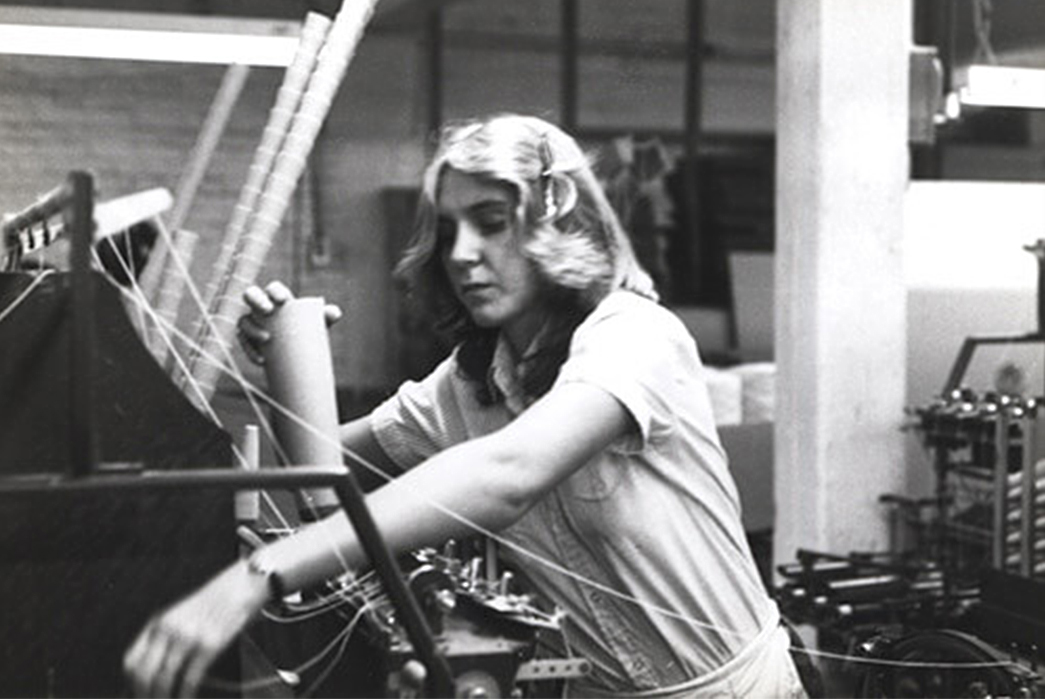

Southern woman working in factory. Image via Southern Spaces.org

From the 1920s onward, unions had been trying to organize the mill-workers in the Piedmont region of the Southern United States: a region that included Roanoke Rapids. The majority of these workers, until the 1960s, were white, and three-quarters of the nation’s textile manufacturing was happening in this relatively small cluster of Southern states.

Despite the fact that these southern mills were responsible for the vast majority of textile production in the U.S., the workers in these mills, on average, were paid less than their Northern colleagues and were far less likely to be represented by a union.

In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Act allowed African-American employees access to more and better jobs in the mills, which stoked racist anxiety among the white employees. This distrust was magnified by many of the mill-owners, as was the fact that minorities were more likely to support unions.

Sensing a potential paradigm shift in the Southern mills, specifically the historically intractable J.P. Stevens ones, the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) sent organizers to the Piedmont region.

According to a paper In Good Faith, between 1963 and 1973, the National Labor Relations Board found Stevens guilty in 21 cases of violating labor laws and the company was forced to pay out $1.3 million in back wages to hundreds of employees fired simply because they’d supported unionization.

This was the tumultuous environment in which Crystal found herself.

UNION

Norma Rae. Image via LA Times

Sutton had been working in one of the seven mills in her home town since the time she was in high school. The workers in the factories often worked six days a week and often for less than $2.80 an hour (roughly equivalent to $15/hr today.).

Sutton had endured almost a decade in the mills and had very nearly reached her breaking point in 1973 when she went to her first union organizing meeting.

By this time, Sutton was in her 30s, had been widowed, and had three children to look after. Her wages simply couldn’t cut it and she began to loathe all the signs of the Stevens company around her. The first meeting she attended was held in a black church, where she was one of only two white women in attendance.

She came to work the very next day with a five inch pin pledging her allegiance to the company and began holding meetings in her house after work. Sutton was immediately noticed by the union, who had almost never seen her ilk, but her conduct alienated her from her community.

Roanoke Rapids was controlled by the Stevens Company and children were taught the tools of the mill trade as well as fed anti-union propaganda as early as elementary school. Because black Americans were disproportionately more in favor of unions than whites, the company claimed that the unions were merely the tool of “Black Power” and similar to today’s rhetoric about immigrants, that these minorities would steal the jobs of “hard-working whites”.

The iconic moment in the Sutton and Norma Rae stories comes later in that first year of her organizing. Her TWUA handler, Eli Zivkovich, had asked her to copy an anti-union letter that had been posted on bulletin boards throughout the Stevens mills.

Her supervisors had forbidden people to copy the letter, which among other lies, asserted that the union was run by African-Americans. The TWUA needed to know what was happening, so Sutton, on a break, began to copy the letter and finished, despite the fact that she was harassed by three supervisors who ultimately threatened to fire her and call the police.

Before they could drag her out of the mill, she got up on a table, wrote “UNION” in marker on a board and flashed it to her co-workers. As legend has it, they began shutting off their machines and giving her the V for victory sign, until the plant was quiet. See the dramatization depicted below in Norma Rae:

Aftermath

Unlike a Hollywood script, the ties between Crystal Lee Sutton’s dramatic last stand and larger changes in the textile industry are hard to connect. What’s certain is that Sutton was a martyr in a larger struggle and by pitching herself into the struggle with her characteristic vigor, was able to win the trust of her co-workers.

The next year, in 1974, workers in Roanoke Rapids voted overwhelmingly in favor of representation by the TWUA (which merged with another union to become the Amalgamated Textile and Clothing Workers Union of America), but it would be another five years before J.P. Stevens signed a contract that guaranteed a $5 minimum wage and established safety and health policies.

Although this fight was lengthy and messy, it drew national attention. For many, these labor battles were the logical next step after the Civil Rights Movement in that noble mission of making a more equal nation.

In fact, Coretta Scott King (the widow of Martin Luther King Jr.) marched with workers protesting at a J.P. Stevens shareholders meeting in New York City. Beyond that, this battle for labor equality was an extremely intersectional one. It united activists from a number of different sectors, and cut across traditional gender and racial lines.

By now, all the mills in Roanoke Rapids are shuttered and most of the mills in the U.S. have vanished the same way. But it’s thanks to brave people like Sutton, that there was any measure of improvement in the conditions within these facilities, even as the industry faltered.

Crystal Lee died in 2009 of brain cancer, the casualty of another corporation after her insurance company delayed her treatment. In an interview shortly before her death she said, “It is not necessary I be remembered as anything, but I would like to be remembered as a woman who deeply cared for the working poor and the poor people of the U.S. and the world. That my family and children and children like mine will have a fair share and equality.” Hopefully her legacy will keep that dream alive.