For the early part of his career, soul music icon James Brown never wore jeans, never wanted to be seen wearing jeans, and wouldn’t allow any members of his band to wear jeans. Denim had a bitter connection for many Black Americans in the 1950s and 60s. Despite the images of Civil Rights activists dressed in immaculate suits and dresses at protests and boycotts, the majority of black people in the post-war American South lived in poverty and worked as sharecroppers or other jobs of manual labor. Manual labor that required workwear.

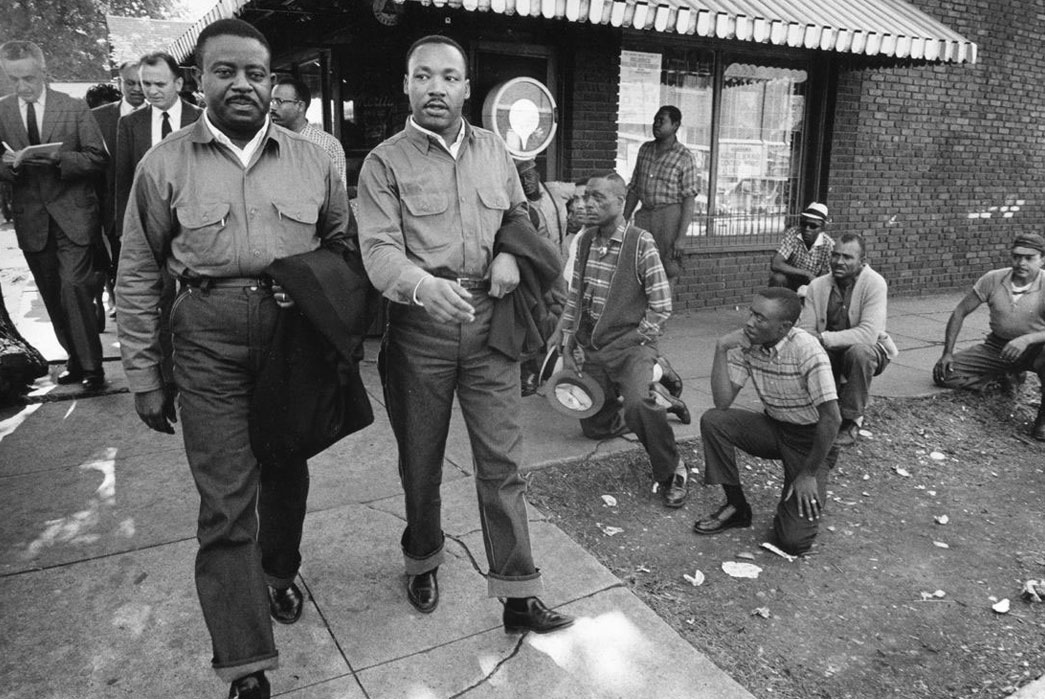

Wearing denim was a function of being poor not of style, and those like James Brown that made it out wanted as far away from it as possible. This logic also played into the strategies of organizers like Martin Luther King Jr., knowing that any and all imagery of people involved in the movement would be criticized harshly for whatever they said, did, or wore. Those involved in sit-ins, boycotts, or other protests of racial injustice often wore their “Sunday Best”, as doing so would play better on the evening news.

King at the march on Selma, Alabama in 1965. Image via US Library of Congress.

However, this strategy had its limits. One of the most crucial aspects of advancing the rights of Black Americans was enabling them to vote. But even registering to vote as a black person in the Jim Crow south could incur the wrath of local law enforcement, the Ku Klux Klan, or other white supremacist organizations. In 1961, a Mississippi state representative murdered voting rights advocate Herbert Lee in broad daylight, a state where only 6.7 percent of black people were registered to vote.

White volunteers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had difficulty making inroads with registering rural voters. These mostly college kids from the north had not only a racial divide but also a class divide to overcome to convince people to put their lives at risk. So they started ditching the collegiate blazers and khakis in favor of the jeans and overalls worn by the people they were trying to win over.

King and fellow activist Rev. Ralph Abernathy arrested wearing denim and workshirts in Birmingham, Alabama, 1963. Image via Prison Photography.

King and Ralph Abernathy were even wearing matching denim work pants and work shirts when they were arrested in Birmingham, Alabama in April of 1963—the arrest that would lead to his iconic “Letter from a Birmingham Jail“.

The look hit the mainstream in August of 1963 with King’s March on Washington. Over 250,000 took to the National Mall in America’s capital to demand civil and economic rights for Black Americans. These quarter-million included many of the workaday Black Southerners who wore their denim to DC.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Joyce Ladner wearing overalls at the March on Washington, 1963. Image via Racked and Getty Images.

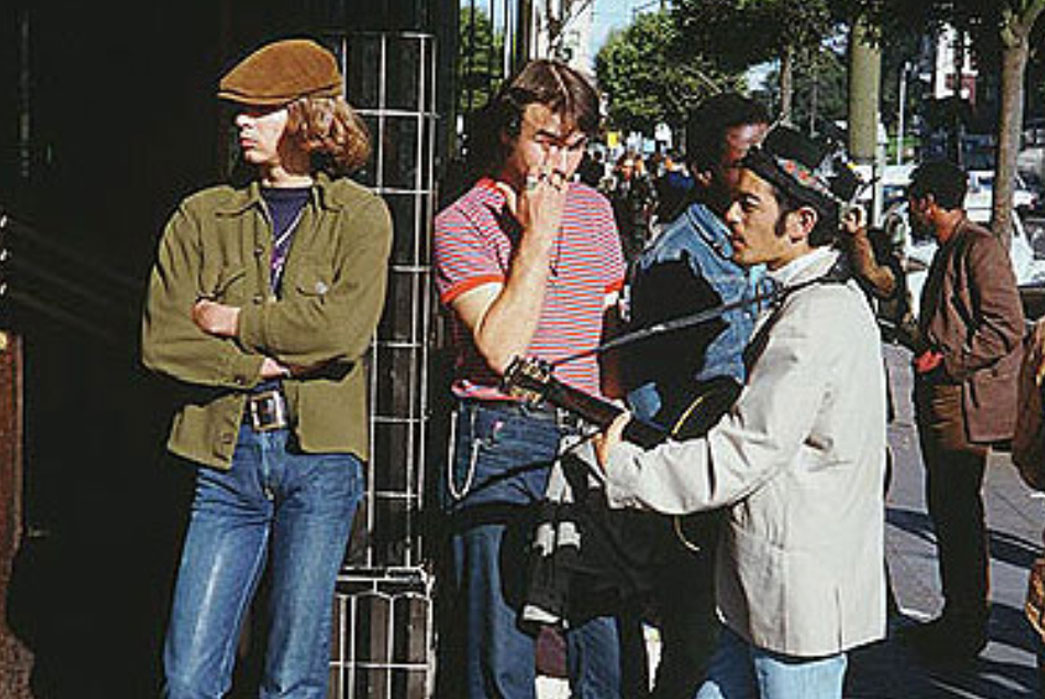

While it’s impossible to ignore the influence pop-culture “rebels” like Elvis and James Dean and Marlon Brando had on the perception of denim in the post-war United States, it’s also plain to see the through line of the workwear worn by progressive Civil Rights activists to that of the counterculture hippie movement that would come just a couple years later.

Workwear clad hippies at San Francisco’s “Summer of Love” in 1967. Image via City of San Francisco.

King was assassinated in 1968, dozens of other Civil Rights advocates died in that same struggle. Now, half a century later, a string of deaths among Ferguson activists shows that still seems to be the fate of those who challenge white supremacy in the United States.

It’s important to remember that for King and other black activists these weren’t styles adopted to suit their personal tastes, but rather an identity forced upon them by a racist system many gave their lives fighting against. A system that continues to this day.