Unless you’re deeply immersed in biker culture, it’s unlikely you’ve had much exposure to biker cuts–vests that were historically cut from denim and leather jackets. And it’s equally unlikely you know much about the “colors” or patches that often accompany these cut-off vests.

Steeped with meaning and reflective of changes in American motorcycle culture, the biker cut isn’t just a piece of clothing to be worn or collected (you’ll probably get your ass kicked if you walk around in one), but a middle finger to the establishment, be it the American Motorcyclist Association or the American government.

Join us today for the history of an underrepresented cornerstone of American outlaw style.

In the Beginning

Capital City Motorcycle Club, 1938. Image via Valcom News

In 1924, the American Motorcyclist Association formed in order to promote the interests of newly-founded motorcycle companies and encourage Americans to take up the pastime. Groups of like-minded folks started donning similar getups, usually heavy-duty sweaters, varsity jackets, and overalls that wouldn’t exactly resonate as tough and biker-y with a modern audience.

The AMA began hosting events and even giving out awards to the clubs with the best overall look, which gave rise to the use of identifying patches for the individual clubs. In the 20s and 30s, these motorcyclists uniforms were practical and safe, but don’t exactly read as “biker” to us today.

You can only seem so badass in riding pants and a cozy sweater. WWII, however, changed the tone and pitch of the motorcycle clubs, and most importantly the wardrobe of their riders.

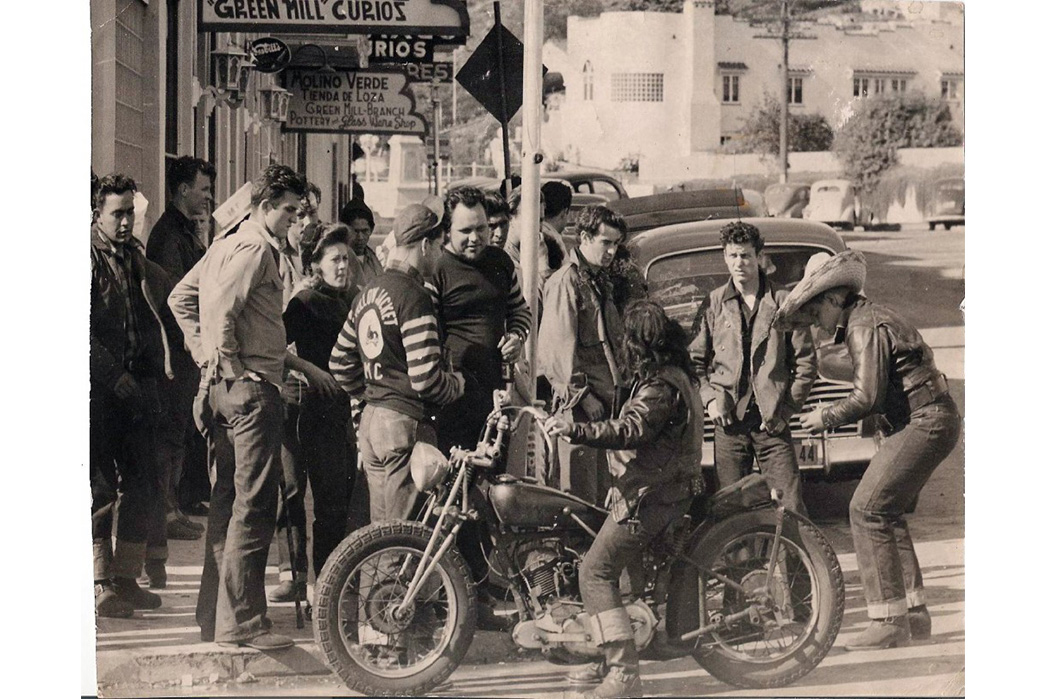

Hollister 1947. Image via Cahiers de Mode.

Veterans came home wearing leather jackets, khakis, and even blue jeans in a debonair, casual way that translated well to the rigors of motorcycle-riding. Although leathers had been worn before the war and Iriving Schott had been manufacturing his iconic Perfecto jacket for some time, they were styled more formally, almost like a piece of suiting.

Strangely, it was the leather flight jackets, brought back by veterans, and not the explicitly designed motorcycle jackets that changed the acceptable styles for motorcyclists. Beaten up by years of flying and often painted with cartoon characters or pinups, flight jackets changed the rules of play–and so after the war, we began to see leather jackets worn more like Brando and less like a model in a Sears catalogue.

Lee Marvin and Marlon Brando in “The Wild One” (1953) which dramatized and exaggerated the Hollister riots of 1947. Image via Brittanica.

World War II marked the largest-ever mobilization of American men in history. A great equalizer, the war brought millions of men into contact with one another in unprecedented ways and in totally foreign contexts. But when the war was over, the American government did their best to shunt them into responsible, productive lives and careers.

A strange shift occurred in postwar America, where men were discouraged from associating too openly outside of work or school. Veterans were expected to marry, have children, and don their gray flannel Don Draper-esque suits and live tame, little lives.

Naturally, ex-servicemen gravitated towards one another to commiserate and slowly recover from their experiences overseas, many choosing motorcycle clubs for the social outlet and as a way to distract from symptoms of PTSD, but their movements were closely monitored.

There are a number of reasons that the Establishment discouraged these groups, but one of the most important was the publishing of the Kinsey report in the late 1940s.

The Kinsey report, though now considered to be deeply flawed, was one of the first widespread discussions of sexuality in America and the book, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male found that nearly 1/3 of its interviewees had had a homosexual experience and that nearly half of men experienced some attraction to both genders (this was obviously conducted with a gender binary in mind).

America’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” relationship with homosexuality had prevented any serious discussion of sexuality and authorities began to look at male-male interactions with more scrutiny and suspicion.

Hollister. Image via Practical Machinist.

Already under scrutiny, one event changed the culture of American motorcycle clubs forever: the Hollister Riot of 1947. The small California town had been hosting the AMA’s annual ‘Gypsy Tour’ since the 1930s but had canceled the event during the war.

1947 would be the first year back and the turnout was far greater than expected. 4,000 motorcyclists descended on the quaint desert village and once drunk, began to overwhelm the town’s seven-man police force. Though there was no serious crime nor any major injury, but an article in Life magazine quickly blew the event out of proportion, to such a degree that in 1953, the film The Wild One dramatized the goings-on as a gathering of criminals and degenerates.

This relatively tame weekend radicalized bikers and changed the landscape forever. When the AMA wrote an article in their magazine after the Hollister incident, they asserted that 99% of all their members were law-abiding citizens and only 1% were outlaws. This gave rise to the Outlaw Motorcycle Groups.

The 1% Outlaws

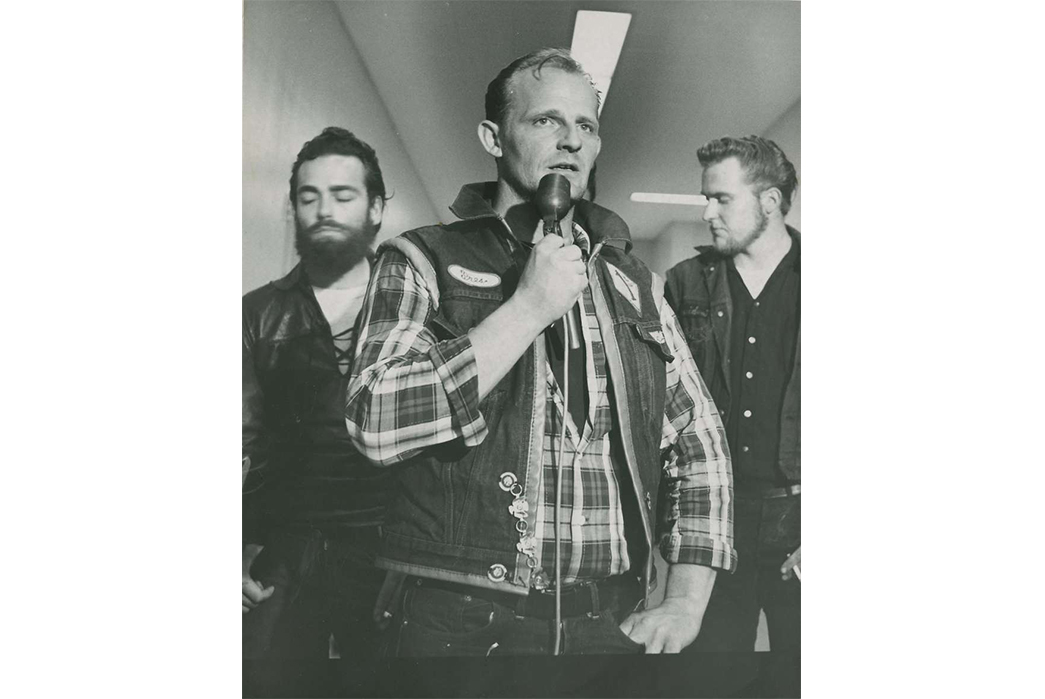

Hell’s Angels member in his colors. Image via San Francisco Chronicle.

The fallout from the Hollister Riot, which had actually been pretty tame, created the much more violent One-Percenter culture that in turn gave rise to the criminal motorcycle gangs. See the diamond patch on the left side of the above biker’s vest? It features the infamous 1% logo, which means that they’re a part of one of the outlaw groups.

The uproar after the Gypsy Tour in Hollister caused the motorcycle clubs to splinter into two major groups, the 99-Percenters, whose groups were officially recognized by the AMA and allowed to participate in their events and the One-Percenters, who were not.

This new divide created a more complex system of marking one’s clothing and the subtle differences spoke volumes.

The Cut

Image via the SF Chronicle.

In the postwar period, even before the Outlaw clubs broke away from the so-called “Family Clubs,” bikers had begun to don cut-off vests, called “cuts,” and attach their “colors”, patches that showed their allegiance. These cuts began as denim, then leather, and finally were available pre-made without the sleeves.

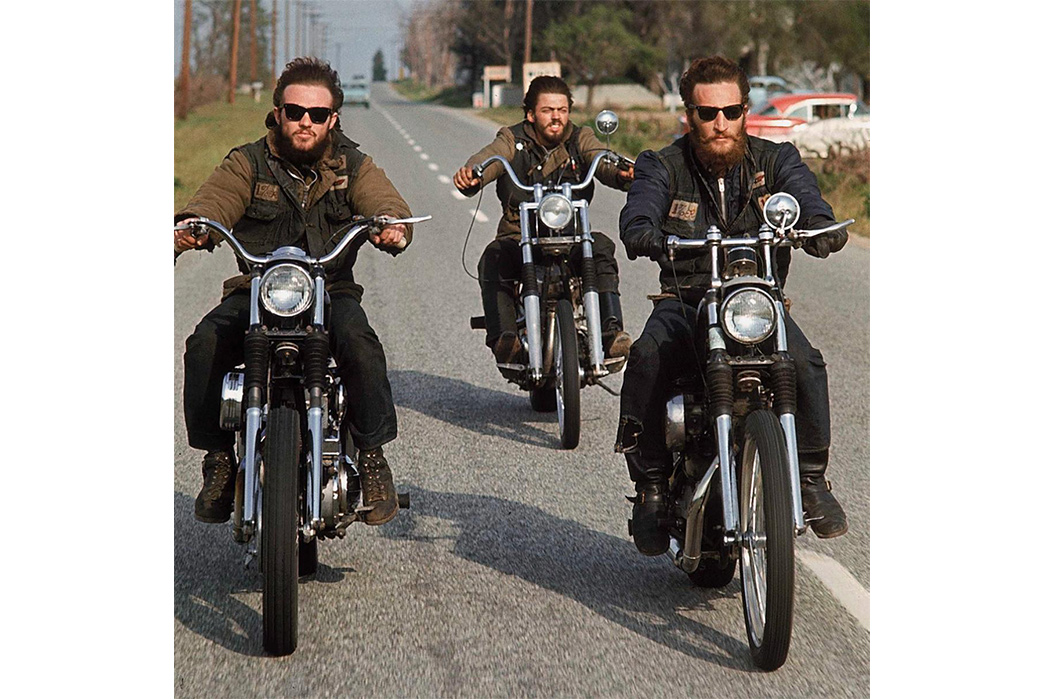

Hell’s Angels mid-60s. Image via NY Daily News.

Denim vests made sense for their versatility and could offer a modicum of protection even in the summer when it was too hot for the rest of the fit but the vests were most iconic when layered over other pieces.

The bikers in the above image have layered their denim cuts over deck jackets. Though the material of the cuts changed over time, gradually transitioning from denim to leather, which was, of course, more practical and safer, the most important part of the cut is its colors.

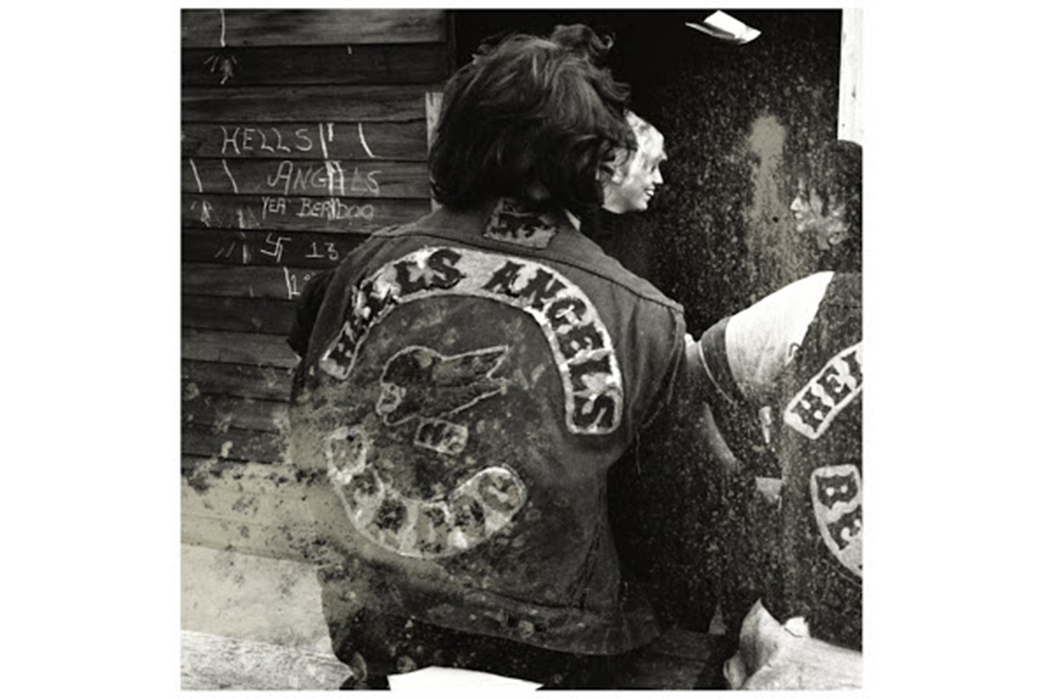

Hell’s Angels Berdoo Chapter, 1965. Image via Life.

Family clubs, which were endorsed by the AMA, typically had colors on their cuts, but these were most often in the form of a single large patch that took up the entire back of the vest.

The outlaw groups, however, would break their colors up into three parts: a central logo that identified their club, and two rockers—a curved insignia that gave the group’s name and another their area of dominion. The front of the cuts feature the rider’s nickname and can also feature the rank if worn by a senior member of the group.

Non-member associates of the bigger clubs, who are usually members of support or satellite groups, are allowed to wear the colors of their controlling, larger club, but never the insignia. If a support member were to wear the main group’s logo, they could be in serious trouble, as full-color members are very controlling about who—if anyone—is allowed to wear their trademark insignia.

The one-percent diamond is also restricted to full-color members of the major Outlaw Groups and are not to be worn by certain clubs or groups.

While the look may be alluring, there is a darker side to the Outlaw Motorcycle Groups. Most of the one-percenters clubs have some kind of criminal connection and the majority of the OMGs are all-white and generally have white supremacist leanings.

Fading Away

Image via Hexis Cyber.

Despite the alarmist articles I’ve read from various government bodies, the fact of the matter is that (for better or worse) motorcycle culture is not what it was. The biggest problem is that the major groups are simply aging out of the culture.

For much of the outlaw biker gangs’ heyday, it was discouraged to have children and the insular, complex group structure often prevented new blood from joining. The clubs/gangs/groups that remain typically have less to do with criminal activity, mostly because the ranks of these groups are no longer populated with criminal ne’er do wells, most have pretty good jobs. And they need to, a new Harley can cost as much as $40,000!

Still, it’s probably for the best to avoid riding with a cut that resembles any of the one-percenters’ groups. A shootout between five rival biker gangs in Waco, Texas in 2015 left 9 dead and 18 injured. It’s anyone’s guess if you stray out into the middle of nowhere, or into a major group’s territory. But despite a sordid, violent past, the one-percenter colors and clubs have made a profound impact on style and pop culture.