While most people know that blue jeans have their origin in the great, late-1800s mining booms in places like California, Nevada, and Colorado, not many have a nuanced grasp of this period’s long-term effects on what has become a ubiquitous classic.

The birth of modern workwear is as much about Levi Strauss as it is about the folks who wore his product into back-breaking and often life-threatening situations. The first wearers of blue jeans lived nearly-unbearable lives in pursuit of a dream. A dream that often killed or mangled them and was usually only attainable for the savvy businesspeople who never swung a pickaxe or lit a fuse.

The garments that would evolve into modern-day wardrobe essentials are often still dug out from the mines in which they were worn and only a select few intrepid fashion historians are willing to track them down and place them in the historical record.

For a period so frequently fetishized by modern brands, it’s important to take a long, hard look at the harsh reality of life for the people who unknowingly created an indelible fashion classic.

Mining Booms

Miner in Jeans. Image via Pinerest.

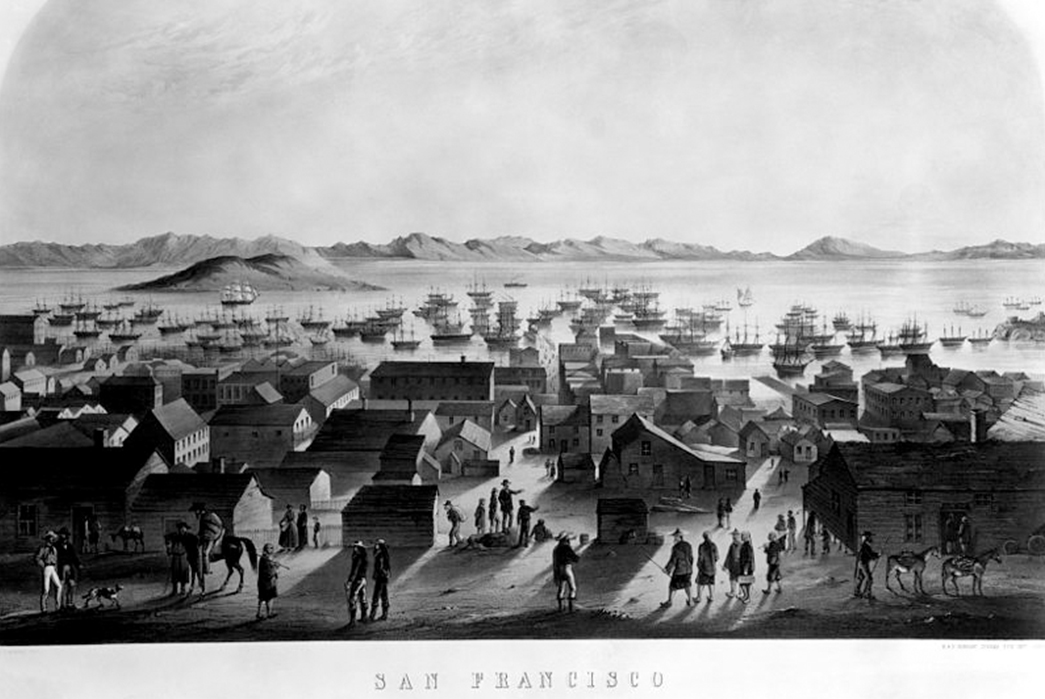

To understand the garments of the late-1800s and more importantly, the folks who wore them, we must take a moment to appreciate the incredible mining booms that happened on the West Coast of the United States. Though the most famous is probably the Gold Rush in California, which basically put San Francisco on the map, there were a number of other rushes too.

There was Pikes Peak in Colorado, which yielded gold and silver in 1859, but perhaps the most significant discovery was that of the Comstock Lode in Nevada, which would turn out to be the largest silver strike ever in the U.S.

The Gold Rush in California began in 1849 and at first was a small, personal endeavor. Single prospectors or relatively unorganized groups of so-called 49ers simply panned for gold, trying to sift through sediment in stream beds to find tiny pieces of ore.

Once this surface supply was exhausted, large mining companies came in and began to excavate for the valuable minerals below, to separate gold from the quartz that surrounded it was a complex and expensive undertaking and unless you had managed to sell your claim to a big company or find enough gold panning, you probably had no way to access it.

The gold-lust raised the population of San Francisco from 1,000 to an unprecedented 25,000 and many people who sailed into the bay simply abandoned their ships behind in order to get to the hills and streams as fast as possible.

View of San Francisco, Overlooking the Bay by Francis Samuel Merryat. Image via Wikipedia.

The great winners in the California Gold Rush were not the prospectors, but the businesspeople who catered to and often exploited them.

The first Gold Rush millionaire was a Mormon businessman named Sam Brannan, who happened to own the only store in the remote Sutter’s Fort area, near where the Gold Rush started. He bought up all available supplies in San Francisco for a pittance, allegedly running through the streets shrieking, “Gold on the American River!” His huge markup and monopoly of the supply market quickly made him an even richer man than he’d been before.

But it wasn’t just mining supplies that could make a businessman rich, there was an untapped market for work-clothes as well. The rigors of mining made it almost impossible for workers to make a pair of work-pants last and new garments were in short supply.

Until 1860, most of the work-clothes available in San Francisco had been manufactured on the East Coast and shipped all the way around the horn of South America at great cost to all involved. It was therefore in the miners’ best interest to repair their pants instead of getting new ones, which created a tailoring boom.

A certain businessman named Levi Strauss established himself by importing heavy denims and duck canvases from the East Coast and then selling them to local tailors who slowly began to make their own product from scratch, often with cheap labor from failed prospectors and new immigrants from China.

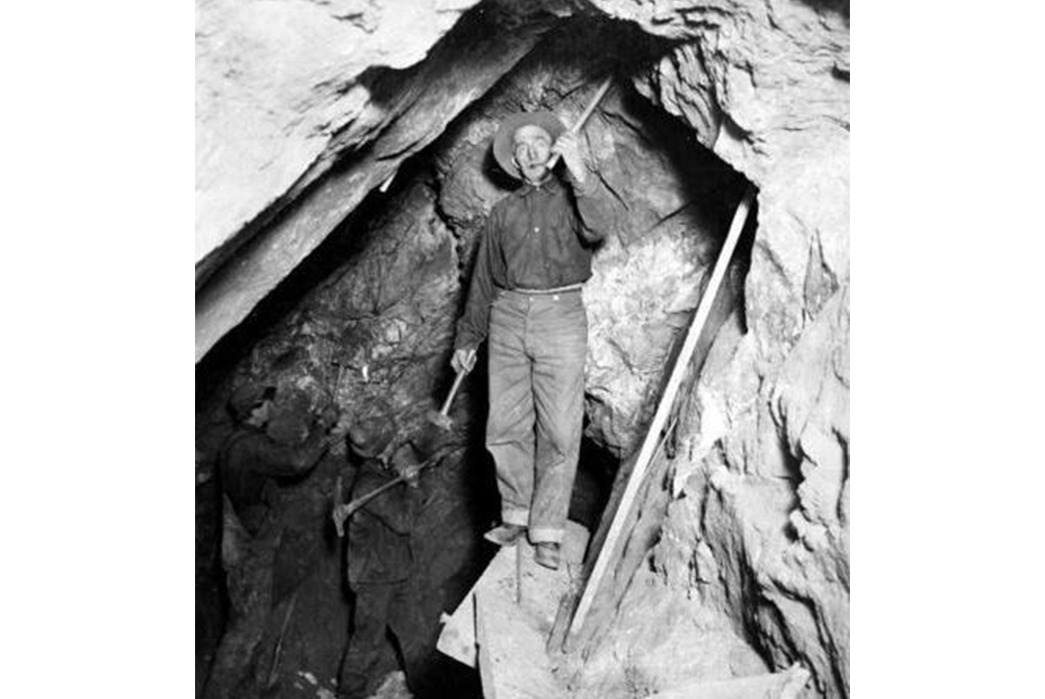

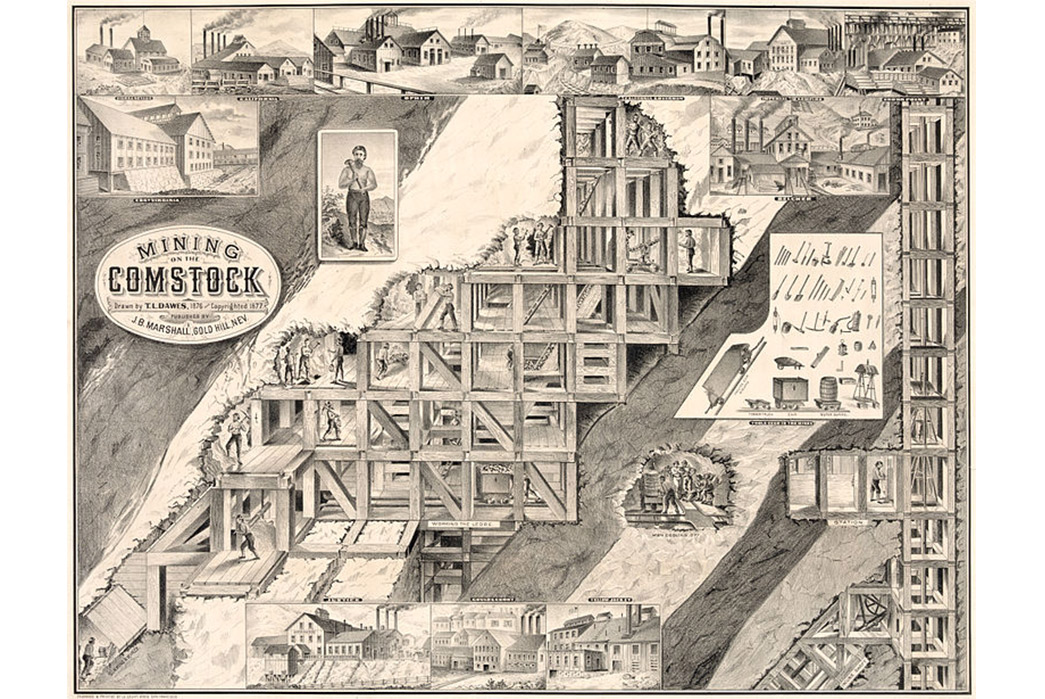

Mining on the Comstock. Image via U.S. Library of Congress.

The silver bonanza in Nevada started about ten years after the Gold Rush and was initially, similarly disorganized. At first, all it took to reach the precious ore was surface digging, but intrepid prospectors quickly exhausted this supply and miners were forced to go deeper to get at the veins of silver.

It was dangerous enough prospecting out West on the surface, but the dangers increased hundredfold once you went down in the mines. Cave-ins were frequent, men could boil themselves alive by accidentally opening pockets of geothermal water, or asphyxiate from poor ventilation in the depths of the mines.

The chaos in Nevada only served to benefit the now-bustling city of San Francisco. California became a state in 1850, as the Gold Rush had petered out and San Francisco served as the port of entry for all goods being sent into Nevada and Colorado, where new communities had new miners who needed new jeans!

A Miner’s Life

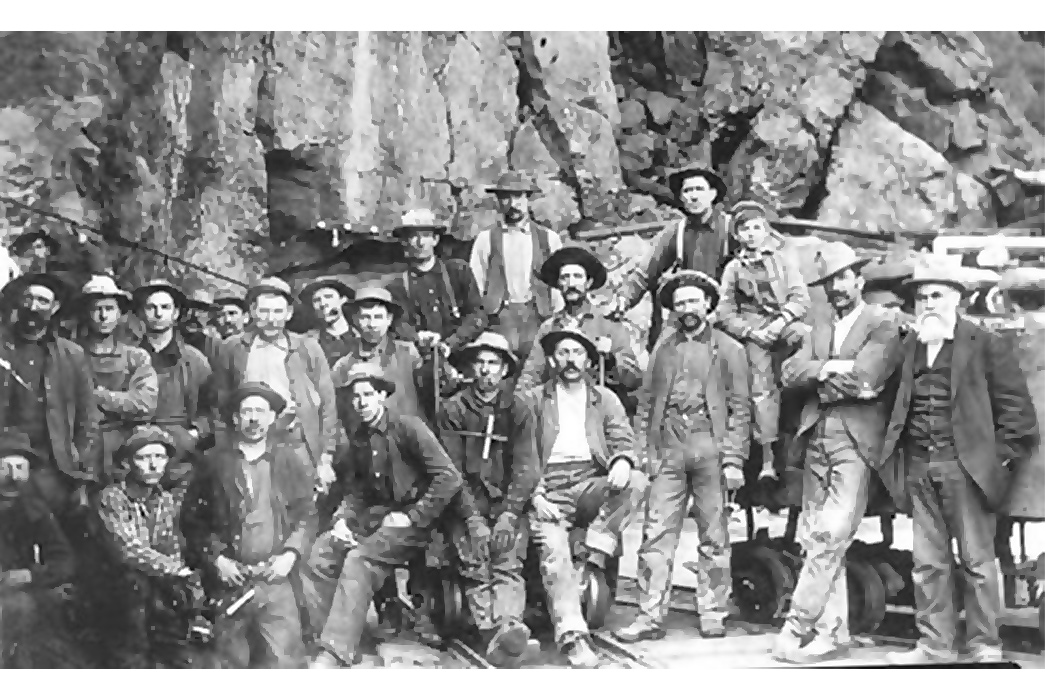

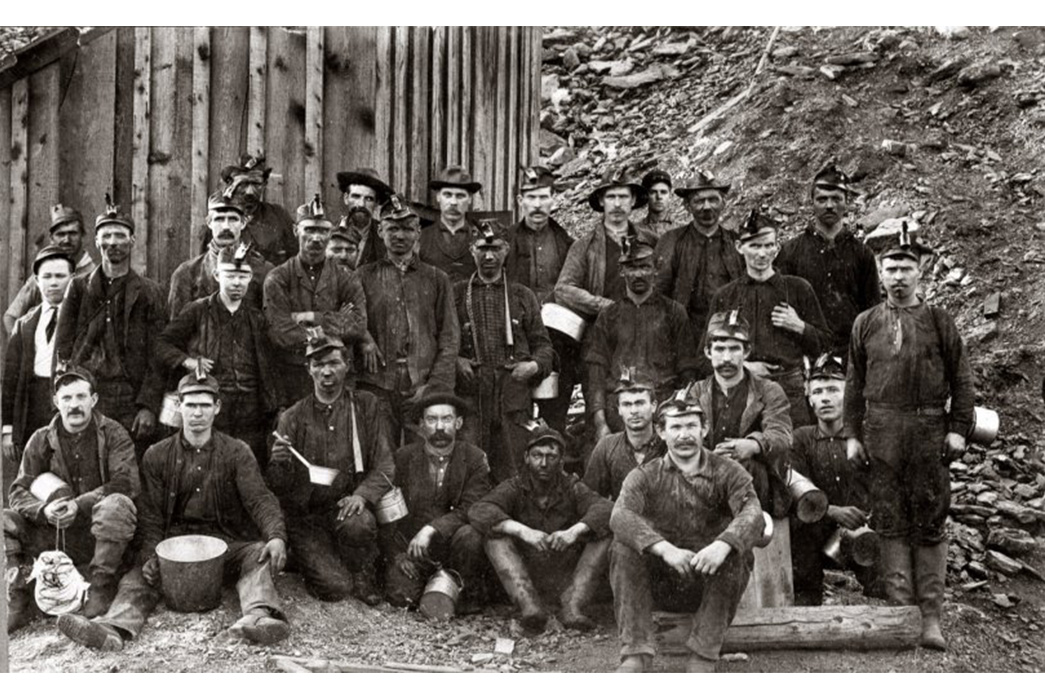

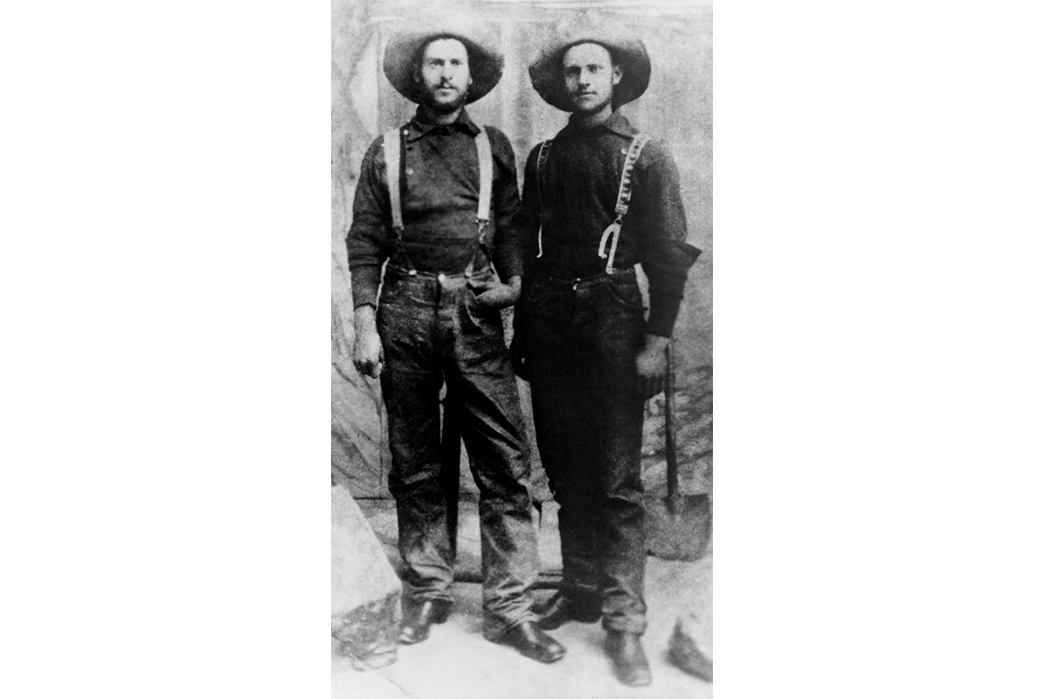

Miners. Image via Shorpy.

Miners’ lives in the late-1800s were absurdly dangerous, large in part because many technologies we now take for granted hadn’t yet been invented. Even outside of the mines, life was uncertain. We can see today, from the ghost towns scattered across former silver and gold country, how folks followed the bonanzas and how later, these towns withered and died without mining to sustain them.

Men outnumbered women 9 to 1 in these raucous mining towns and though the people were incredibly diverse, the best work was reserved for white men. Native Americans were distrustful of mining (and rightfully so), but many other miners of color sought work where they could get it.

At the dawn of the gold rush, a prospector could make a living from staking a small claim, but once the surface supply ran out, these prospectors were forced to find other work. Mark Twain writes extensively of the trials and tribulations of the prospector, who had to do a certain amount of work on his claim in order to hold onto it, the goal, if not to get rich, to at least find enough ore to convince a larger entity to buy up your stake.

Twain and his compatriots staked a claim only to learn just how much time and money the endeavor would entail in his book Roughing It:

Therefore instead of working here on the surface, we must either bore down into the rock with a shaft till we came to where it was rich – say a hundred feet or so – or else we must go down into the valley and bore a long tunnel into the mountainside and tap the ledge far under the earth. To do either was clearly the labor of months; for we could blast and bore only a few feet a day – some five or six. But this was not all. He said that after we got the ore out it must be hauled in wagons to a distant silver mill, ground up, and the silver extracted by a tedious and costly process. Our fortune seemed a century away!

The allure of silver and gold were great, but the costs of actually hauling the precious metals out of the earth were far too prohibitive for most small operations. Many chose, as Twain ultimately did, to go with a more stable source of income instead of the uncertainty of mining, “…I abandoned mining and went to milling. That is to say, I went to work as a common laborer in a quartz mill, at ten dollars a week and board.”

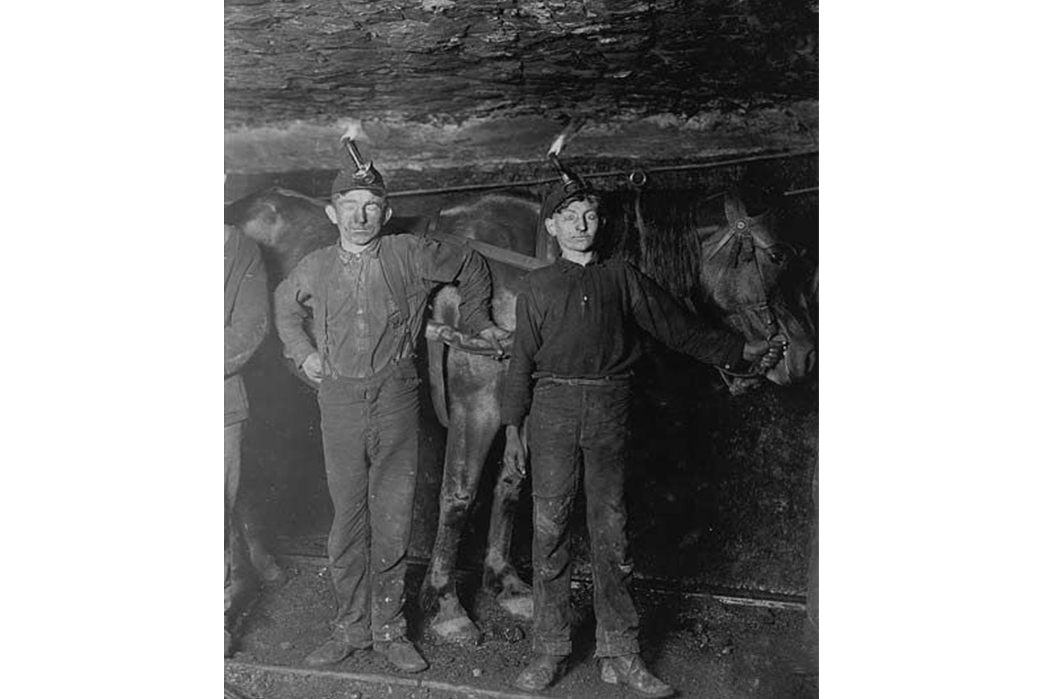

In many ways, the miners who went to work underground in Nevada and elsewhere in the late-1800s were guinea pigs. Square set timbering, the practice of building perfect cubes to account for the sporadic pockets of ore unique to the Comstock Lode, solved the deadly cave-ins that had been endemic to site, but only after countless lives had been lost.

Greedily delving deeper and deeper into the earth eventually led to other advancements like pumps to get fresh air down the bottom of the mine, but these novel new creations didn’t always work as planned and one wonders how many perished for want of air in the depths of the silver mines.

In 1859, at the start of the silver boom, Americans had almost no experience in processing silver and all manner of techniques were tried, typically with highly toxic chemicals. Mercury, cyanide, and others were used to separate silver from its surrounding quartz, with grave costs to the environment and undoubtedly to the workers in the mills.

Poisoned, crushed, or frozen to death, being a miner, miller, or prospector was a pretty raw deal and they needed supremely hard-wearing clothes to protect them as much as was possible.

What the Miners Wore

Image via Pinterest.

A man named Jacob Davis was one of the tailors who followed the silver frenzy eastward into Nevada. His small, but thriving shop catered to the local miners who blew through pants at a breakneck pace. Davis’ shop in Reno specialized in made-to-order work pants for men too large for the ready-made stuff coming from San Francisco.

As the legend goes, one particular customer continually blew out his pockets, from carrying rocks back and forth from his dig-site and his wife was fed up with the cost of repairs. On a whim, Davis decided to reinforce these “points of strain” with rivets, like those used on saddles.

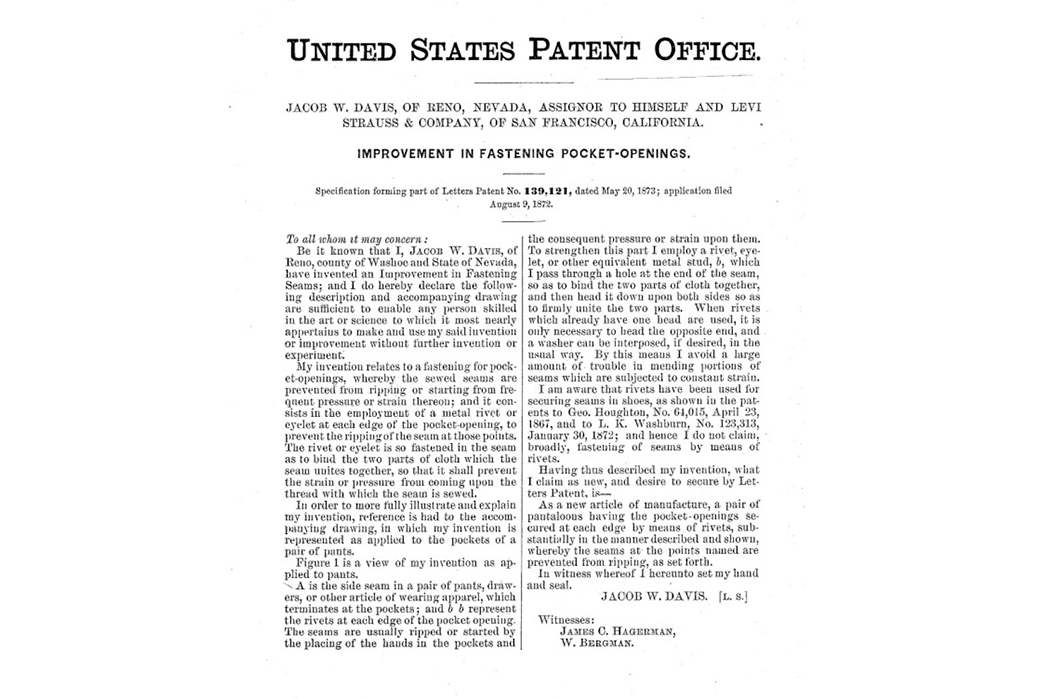

The patent that changed it all. Image via US Patent Office.

When Davis’s reinforced waist overalls performed even better than expected, he was suddenly overwhelmed with orders. He knew he only had a matter of time before this idea was taken from him, so he wrote to his fabric supplier, Levi Strauss, for assistance filing a patent.

Strauss agreed, and on May 20, 1873 their patent was granted. Levi offered Davis a job as a foreman in his plant, making the reinforced pants of his own design and thus Levi’s jeans was born. The new product was so popular and lasted so much longer than anything else on the market that they were able to charge a markedly higher price and still sold them in droves.

Levi’s competitors quickly realized they were outgunned and scrambled to create a similarly effective modification to improve their jeans’ durability. The only caveat was that Strauss and Davis held the patent and for seventeen years after its filing, no one could copy their rivets idea.

Greenebaum Brothers’ jeans. Image via Pinterest.

What resulted was essentially a reinforcement arms race. Whoever could create the toughest jeans would win the support of the miners, who were willing to pay a premium for a product that lasted longer.

Jacob Greenebaum was a partner in Greenebaum Brothers, an outfitter and Levi’s competitor, whose solution to the patent was to place leather triangles where rivets would go on a pair of Levi’s. Because of this competitive atmosphere, Levi Strauss (with Jacob Davis’ expertise) constantly tweaked their work pants to stay ahead of the curve.

Michael Harris, in his incredible book, Jeans of the Old West, tracks many of the other competitors who attempted to replicate the success of the riveted Levi work pants, but as he is quick to mention, few of these examples are left. There were many patents filed in the 1870s to keep pace with the success of the new Levi’s jeans, but it’s often hard to connect these patents with manufacturers or actual remaining artifacts.

1880s Levi’s. Image via Gold Detection Forum.

Made in 10oz. duck and 8oz. denim (the heaviest available at the time, possibly milled at Amoskeag Mills), the riveted waist overalls supervised by Jacob Davis were of supremely high quality. The seams were straight, the copper rivets strengthened the crotch, pockets, and eventually the back cinch.

Over the brand’s first twenty years of production, they constantly tinkered with the cinch strap until it was as strong as humanly possible and they weren’t shy about suing anyone who copied their design, setting a litigious precedent that endures to the modern day. However, the design was somewhat in flux and some jeans featured extra details like a fifth tool pocket on the side of the leg or reinforced knee panels.

Davis’ rivet idea was a shock to the system for the western workwear industry and a surreal race to make the best jeans possible took place. Although there were cheaper alternatives, often sold direct to the mines and mills, the big garment houses tried desperately to get a leg up on one another and manufacture the absolute best product possible.

Pretty much the exact opposite of today’s fast fashion culture, brands couldn’t cut corners, or they could lose the support of the miners who wore their pieces. This devotion to durability extended over time to encompass Levi’s blouses, shirts, and their evolving line of jeans. Levi’s competitors, many of whom have been lost to the sands of time, like Boss of the Road, and other more notable brands, like Lee were all informed by this ethos of strength, integrity, and ingenuity.

Image via SF Chronicle.

For people who worked in environments where death and ruin lurked around every corner, a life-line was needed. You couldn’t trust your foreman at the mill to pay you for your work, you couldn’t trust that your stake would be the big one, and you couldn’t trust that your partner wouldn’t shoot you in the back if you struck a lode—but you could at least trust your jeans, especially if they were Levi’s.