Until a few weeks ago, I’d never heard of “PPE,” and though most of us know exactly what “Personal Protective Equipment” looks like, I doubt we were universally familiar with the acronym. Because we’re hearing about PPE in the context of the current pandemic, it’s easy to assume that it refers solely to things like medical masks and scrubs, but that’s not true.

Personal Protective Equipment is really anything that protects your person, be it steel-toed boots, bullet-proof vests, or hard hats.

Image via Fox4News.

Although PPE reaches across many industries, from construction to porn (duh, condoms), we’ll be focusing on the history of those humble little masks and gowns that are currently in such short supply. The history of medical PPE is a fascinating one, tied closely to the evolution of medical theory and running concurrent with important inventions that changed the world.

Modern Medical PPE

Full PPE setup. Image via Daily Beast.

Modern doctors have a wide range of PPE options at their disposal (when supplies last) all of which are designed to prevent contact with contaminated surfaces and objects and halt the transmission of infectious diseases.

For most of us, our contact with PPE in a medical setting had historically been fairly mundane and low-stakes. Unless we’d undergone some serious surgery all we’d been exposed to was dentists and doctors gearing up for cleanings and checkups.

Now, for the first time, many of us are coming to understand just how crucial PPE is in a medical setting, especially one as infectious and lethal as we’re seeing today. For medical professionals treating Covid-19 patients, it’s not enough to simply wear masks and gloves. Scrubs, face shields, eye-wear, and full-body suits are also required, but unfortunately in dangerously low supply.

As often is the case with progress, the evolution of PPE was slow, as the protection of patients and doctors could only advance with changing currents of scientific thought.

Before there Were Germs

Trust him, he’s a doctor. An engraving of a plague doctor, circa 1656. Image via Wissen Media.

Plagues and pandemics have ravaged humanity as long as there have been humans to ravage, but our protective equipment could only evolve as fast as our collective scientific understanding. That being said, philosophers and prominent thinkers had tried for centuries to determine the cause of sickness and how these sicknesses spread.

The earliest theories about disease and sickness had to do with something called “the humors.”

A now-thoroughly debunked theory, humorism has its written origins in Ancient Greece, but likely its ideological roots date back even further, possibly to Ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia. Hippocrates is the first to have associated the humors to health and narrowed them down to four fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile.

It was thought that good health was a result of well-balanced humors and that any severe imbalance was the cause of all disease. This imbalance was called “dyscrasia” and could only be treated with herbs or by lessening the amount of the excessive humor.

The main problem with this theory (there are of course, multiple) was that it traced all sickness to a person’s humors and didn’t have room to interpret contagious disease. There was no medical PPE to speak of until humorism was phased out in favor of the equally-debunked, but slightly more accurate “miasma theory.”

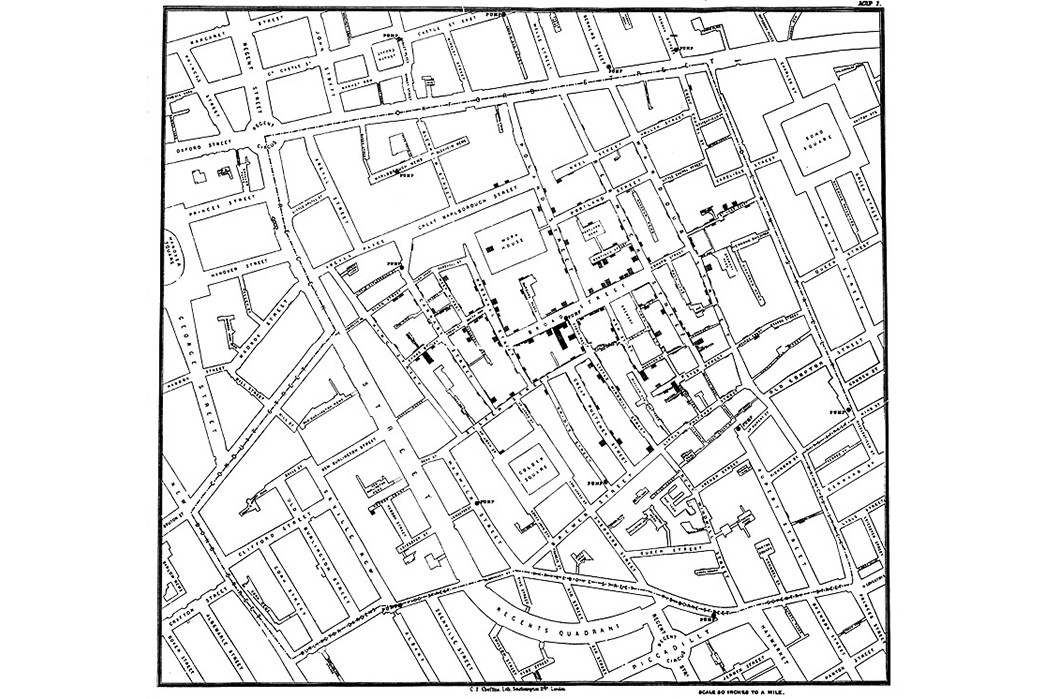

John Snow disproves the miasma theory. Image via On the Mode of Communication of Cholera

The miasma theory attempted to understand the spread of illnesses like the bubonic plague and cholera with something called “night air.” Night air or bad air was supposedly the air that emanated from decomposing organic matter, which was thought to transmit disease.

Though obviously bogus, the miasma theory at least drew a connection between bad-smelling decomposing things and sickness. The reason the plague doctors wore those strange masks with the beaks, was that their beaks were stuffed with herbs meant to protect them from the bad air they might otherwise inhale.

The Miasma theory would be disproven by several scientists, one of whom had the Game Of Thrones-esque name of John Snow. Despite the theory’s illegitimacy, it did push medicine and public health in the right direction. Poor hygiene, bad smells, lack of public sanitation; all these were attributed to disease and caused widespread efforts to keep things tidy and clean-smelling, which lessened the infectiousness of some places, but of course not for the right reasons.

Miasma theories led to huge public sanitation reforms in London in the mid-1800s and also heavily influenced Florence Nightingale, who is often referred to as the mother of modern nursing. She widely advocated for hand-washing, which decreased deaths in her ward; but again, this was to combat the bad air, not because she had any understanding of pathogens.

Until the discovery of germs and some massive changes in medical thought, PPE wouldn’t really exist, but miasma theory began forging the connection between some kind of protective or clean garment and personal safety.

Steps Forward…and Backlash

Surgery in the 1840s.

In the mid-1800s, massive epidemics caused some profound shifts in European scientific thought. Though other regions of the world, namely the Middle East, were lightyears ahead in terms of understanding germs and health, things were moving more slowly in Europe.

The aforementioned John Snow was one of the first European scientists to successfully challenge the miasma theory. By interviewing Londoners, he was able to trace a number of cholera cases to a public well, which in turned out, was both drawing water from sewage-contaminated parts of the Thames and was dug perilously close to a cesspit, which was leaking cholera-infected fecal matter into the water supply.

His 1854 discovery was so convincing that the city closed down the well and ending the cholera outbreak. However; his chief theory, that of a fecal-oral infection, (confirmed after his death) was too unpleasant and scientifically complex for his contemporaries and they were rejected outright.

Even as medical professionals began to understand the nature of epidemiology and the way disease could spread (via pathogens and not smell), the adoption of more stringent protocols in operating rooms and other sensitive areas was slow in coming.

A study in Anesthesiology analyzed all available photographs online from the first unposed surgeries in the 1860s until the 1960s and found that it wasn’t until after 1950 that every person in the O.R. was dressed in accordance with modern standards—meaning gloves, masks, scrubs, and caps.

In fact, in the early days of surgery, surgeons took it as a point of pride to undertake operations in their finest street clothes, and complete the procedure without getting a single drop of blood on themselves.

The adoption of these personal protective measures were slow and often up to the discretion of singular surgeons. Paul Berger, a French doctor, is widely attributed as the first person to wear a mask during operations.

In his case, he didn’t fear being infected by his patients, rather the other way around—he’d been harboring concerns that saliva projected while talking to his colleagues, was entering his patients, causing infections in otherwise clean operations. But even after he saw a dramatic drop in infections after wearing his mask, his colleagues still derided his choices.

One famously said, “I have never worn a mask, and quite certainly I never shall do so.”

Surgical gloves, as we know them today, weren’t even possible to make until Charles Goodyear’s famous discovery of vulcanization. The very first rubber surgical gloves were made by Goodyear in 1893 for an aptly-named Dr. Bloodgood who had them primarily brought into the O.R. because the acids used to sterilize instruments had been irritating his hands.

The fact that his patients had miraculously low rates of infection was a coincidence.

By 1920, masks in the O.R. were common practice and the first mention of properly worn gloves appeared in a nurse’s handbook in 1916, but the lag-time between the discovery and it’s widespread adoption was always drastic and could have cost many lives on the operating table and in general practice.

PPE In a Pandemic

Donald Trump publicly refused to wear a face mask, despite CDC guidelines. Image via National Post.

Far from a clear progression, medical history is a convoluted web of independent discoveries, with much backtracking, debate, and mockery of trailblazers. Unlike certain aspects of the field, PPE is never invasive and certainly isn’t dangerous to medical practitioners or patients.

It baffles a modern reader, how someone, anyone could brazenly fight against a measure that can only reduce risks and help the weak and sick.

Even now that the CDC has recommended that all Americans wear face masks when out and about, our own president refuses to follow that directive. What is it about people? What is it about the surgeons who refused to use gloves or masks? What is it about those who refused to further investigate when John Snow was on the verge of curing a disease?

Be it machismo, ignorance, or something more sinister, history shows that taking the safest route is never the wrong call. If you at home have been hesitant about throwing on a bandana, scarf, or even an amateur or pro homemade mask when you go to the grocery store, please consider it. We can only save lives from here.