J.Crew‘s filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy marks the first of the major American retailers to fall during the Covid-19 era, but the collapse of this retail giant has a lot less to do with coronavirus and a lot more to do with ineptitude, financial mismanagement, and overall lack of identity.

There has been no shortage of articles that bemoan the bankruptcy of J. Crew and begin to speculate on the demise of American retail. J. Crew may be a harbinger of things to come in the Covid era, but only because the company’s pre-Covid conduct cemented its fate.

Large-scale retail is obviously not the only American institution we can accuse of whistling past the graveyard. The phrase, if you’re unfamiliar, lampoons the practice of acting like everything is perfectly fine even though misfortune is right around the corner. Not only did many American institutions, including J.Crew, act like everything was perfectly normal, they built themselves into a house of cards that could only function under the most ideal conditions, one that would collapse with even with the gentlest breeze.

The Coronavirus and the shutdowns that have been necessary to curb its transmission are less like a breeze and more like a gale-force wind. It has brought some of the most powerful nations in the world to their knees, so it’s no surprise it brought down J.Crew.

The House of Cards

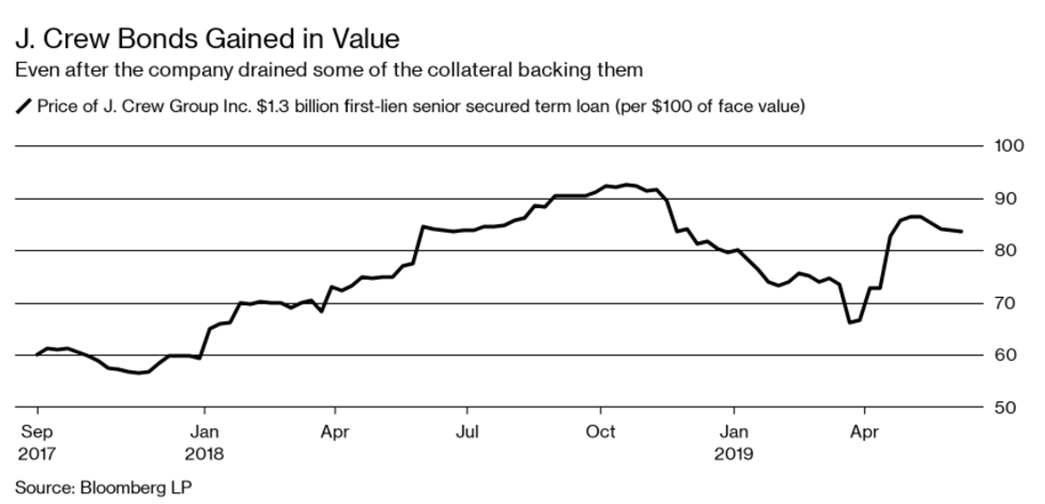

Image via Bloomberg.

In 2016, J.Crew was in such dire financial straits that they needed a huge loan to stay afloat. The problem was, they had no assets left to use as collateral. Literally everything the company had of value was already being used as collateral in other loans. (As of 2011, their debt load was $1.3 billion.)

In a move that feels more like an episode of Succession than reality, the company put the J.Crew brand name as well as its intellectual property into a new entity in the Cayman Islands in order to leverage that as well.

The company essentially shed its very identity, in order to obtain a huge, new loan. They borrowed $300 million from Blackstone Group LP, using the freshly-diverted intellectual property in the Caymans. According to the above graph by Bloomberg, J.Crew’s use of this loan actually increased consumer confidence, but at a tremendous cost.

The brand’s original lenders were incensed when they heard the news. What is the value of a brand when it’s sold the very pieces of itself that make it a brand to another lender? According to Bloomberg, since that deal, investors fear being “J.Crewed”, being hit by a deal that backdoors the value of their collateral to another entity (although Imogene + Willie appear to have pioneered this practice in 2013).

But the deal speaks to a larger trend that has concerned federal regulators for some time, namely the proliferation of collateralized loan obligations (CLO). These leveraged loans are granted to companies with low credit ratings or who wouldn’t be allowed to increase their debt in any other circumstance.

By some measures, American companies’ debt is 7.7 times their annual profits and oftentimes this debt can be increased with the use of private equity firms and these rather lax loans.

Because most of these CLO loans are held by non-banks, (85% at last count) it’s hard for regulators to know just how much debt is out there and who really owns what. CLOs are somewhat predicated on the rest of the economy running smoothly and when things go off the rails, the house of cards can come crashing down.

A Shell of Itself

Image via J Crew Factory.

In a scathing NY Times piece on the J.Crew bankruptcy, Vanessa Friedman accused the brand of being creatively bankrupt as well. Though, initially it feels fair to level this accusation at the majority of large fashion brands, a cursory scan of the other mall brands’ websites highlights the J.Crew dilemma.

Even a quick visit to the home pages of some other fast fashion giants like Forever 21, H&M, and Banana Republic, shows, if not a cohesive identity, at least faces and styles that seem in line with trend and contemporary standards.

While J.Crew selling itself was a financial move, it also shows the disconnect between the creative part of the brand and the people running the show. At the end of the day, J.Crew was just a machine accruing debt and its creative choices and intellectual property were merely supporting that.

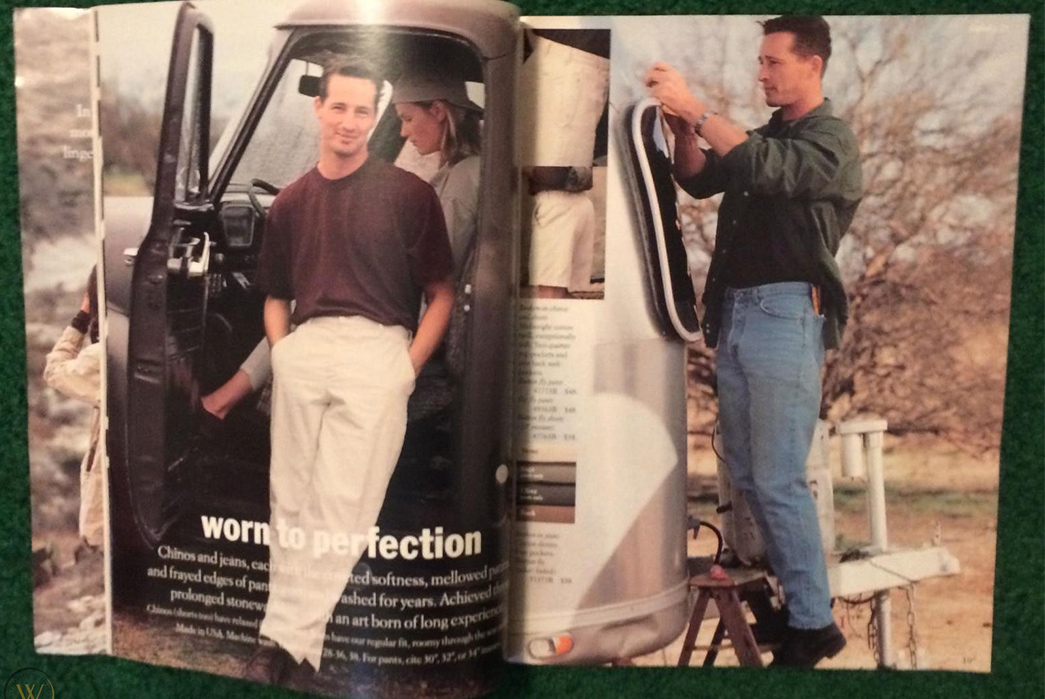

We can partially write off J.Crew, with its uniquely Northeastern vision of prep as being out of touch and white-washed, but their mediocrity is harder to pin down. After J.Crew’s risky financial footwork, the brand became a revolving door for executives and creatives alike and the resulting pandemonium left the brand with a vision of itself that was as generic as possible to please as many as possible.

Its unique brand of Martha’s Vineyard prep wasn’t its downfall, after all, Vineyard Vines and Sperry are still in the game. However; it feels like the brand was continually changing course, even skirting around its own strong suits to appease a wider demographic. Who exactly makes up that demographic is hard to say—Michelle Obama’s endorsement of the brand in the late 2000s was a huge victory for J. Crew, but not enough to guarantee its lasting success.

J.Crew served for many male consumers, as a gateway to a more refined style. Their flirtations with Japanese denim and collaborations with brands like Red Wing and Alden introduced customers to a new tier of quality, not often seen in shopping malls.

Clearly, pressure from cheaper brands, like Zara rattled the highers-up and it feels that, instead of maintaining a commitment to quality, refinement, and their own prep heritage, J.Crew stuttered.

Chapter 11

J. Crew catalog Fall 1993 (more of this please!). Image via Worthpoint.

It’s deeply saddening to know how J.Crew’s many employees nationwide could suffer in the fallout of the brand’s bankruptcy. But with the context of their huge debt burden and desperate attempts to borrow their way out of the red and into the black, it’s not so surprising that they’re falling apart.

J.Crew will undoubtedly resurface after reorganization, but unless the brand does something to distinguish itself, what point does it serve except to pay its executives’ salaries? The brand’s current wish, which seems to be dressing us as watered-down, bargain store Kennedys doesn’t really resonate right now and in this writer’s humble opinion, they should either get back to the quality that earned their name in the first place or fully embrace the descent into fast fashion.