When the Coronavirus began sweeping the globe, the world’s largest fast fashion retailers started taking unprecedented measures to shore up their inevitable losses. But with supply lines that stretch across continents, their decisions to cancel hundreds of millions of dollars in orders came with a cost. The consequences of these cancellation rippled outwards, driving millions out of work and bringing some of the largest garment suppliers all over the world into deep financial trouble.

Urban Outfitters invokes force majeure clause to get out of contracts during covid. Image via Ethical Corp.

According to the Wall Street Journal, in April alone, consumer spending in the United States fell 13.6%, the most significant drop since 1959. The Covid-19 pandemic, with its requisite stay-at-home orders has dramatically changed consumers’ spending habits and many sectors of the economy responded with appropriately drastic measures.

Even under the best of circumstances, fast fashion supply lines can be extremely disjointed. The relationship between supplier and retailer is almost always asymmetrical, with the vast majority of the power residing with the (usually Western or American) retailer. In the last few months, these retailer cancellations have been so pervasive that many garment workers in places like Bangladesh are facing uncertain job prospects.

Power Structures

Top Shop. Image via Business of Fashion.

In the last ten years, the balance of power has shifted even further in favor of the big buyers and brands with the transition to the “open-account system.” As opposed to letter of credit, which guaranteed payment by banks, even in case of force majeure, suppliers are now essentially forced to agree to an honor system. With “honor” a seemingly limited commodity among fast fashion megaliths, the system failed suppliers even under the best circumstances.

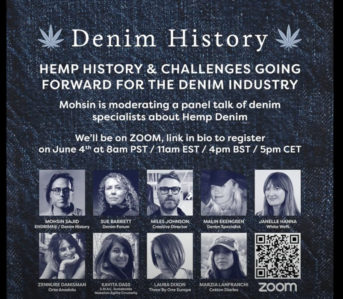

Denim Historian, educator, and owner of brand Endrime, Mohsin Sajid, explained the way the new, flawed system works:

It’s all on credit. So, you have a letter of agreement—or let’s just say, a company in New York will go make 50,000 pieces of a pant. They’ll go over to Pakistan and they’ll order it there. And they’ll say, “Okay, these are the terms. Once we agree on it, you have to make it and deliver it within 20-30 days and then after maybe 45 days, we’ll pay you back after you’ve delivered it.

“So, you need to do all the work, buy all the fabric, all the trims, and jump through hoops for us and it has to be delivered on this exact date for us. And if you don’t deliver it on this day, then we’re going to ask for a discount, even if one day late, and then we’ll pay you off after 45 days.”

Not only must suppliers front all the expenses, they must finish enormous orders within extremely tight windows—facing huge losses if they run even a day behind schedule. This lack of accountability on the part of retailers allows them to operate with impunity. Blake Ulves, formerly of Modern Cotton, is familiar with this malfeasance even in domestic manufacturing. “What if the market changes and they say, ‘Sorry, we have to cancel it.’ Or, ‘We’re only gonna take in half your supplies.’ I can’t afford that kind of thing.”

Even in a booming economy, there was no way for suppliers to guarantee they would be paid what they were owed for their labor. If a buyer felt the styles were out of date, they might cancel the order, if the buyer simply didn’t need the inventory, they could cancel the order.

Even if a supplier pulled a multimillion dollar order together in time, they might still have to wait nearly three months to receive payment, in which time, they’d need to keep the factory running and move on to new orders.

COVID Exacerbates Iniquity

Big-Retailers-Cancel- Orders-A-garment-worker-in-Bangladesh.-Image-via-Apparel-Views.

Unfortunately for suppliers and their many employees, the unfairness of these honor-systems were fully exploited by large retailers during the COVID-19 epidemic. Arcadia Group, which owns the likes of Topshop, Miss Selfridge, and others; has been one of the most notable offenders, canceling finished orders to avoid paying.

Other companies, like Urban Outfitters, have pleaded force majeure to weasel out of paying for orders that are already completed. “Now they’re finding loopholes not to pay,” Sajid explains, “‘Oh, the color was wrong, now we have to change the color. Six weeks ago we wanted a particular red, now we want it to be a different color red.’ So they’re trying to get out of paying.”

These drastic (and often devious) measures might keep the lights on for struggling U.S. and U.K. retailers, but the consequences affect the lives of factory-owners, their employees, and unfortunately—even the employees’ families.

It’s no secret that fast fashion giants have exported labor to the far corners of the globe in order to obtain product as cheaply and quickly as possible. It is in these countries, where labor laws and social protections are lax enough to allow for this style of manufacturing, that people are suffering the most. Particularly hard-hit is Bangladesh, which is the world’s second-largest garment manufacturer after China.

A unique confluence of factors has caused Bangladesh to be one of the most vulnerable nations to these huge cancellations, and unsurprisingly, the majority of these factors are the work of the same Western retailers now screwing them over.

Bangladesh post-Rana Plaza

Memorial for the sixth anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster. Image via NY Times.

In 2013, a huge disaster in a Dhaka clothing factory turned the world’s gaze towards Bangladesh. The Rana Plaza disaster claimed the lives of 1,134 people and injured some 2,500 more. The horrifying collapse of the eight story building led to sweeping reforms in Bangladesh’s garment industry, much of which came at the behest of Western retailers.

Before the Rana Plaza disaster, large Western companies like Primark and Calvin Klein had been more than happy to occasionally audit their Bangladeshi factories, or simply take the owners’ word that things were safe, despite the fact that injuries and deaths were commonplace. It was only when thousands were killed and injured that these same brands were forced to take accountability, not out of the goodness of their hearts, but for fear of western boycotts.

Two large agreements, signed by European and American brands led to inspections of 2,500 factories and blacklists of nearly 300, leading to significant improvements in worker quality-of-life. Retailers, through the agreement, were also forced to reveal the locations of their factories, in hopes transparency would further increase accountability. It would appear that everyone won in these negotiations. The bad actors were taken to task and retailers would have the peace of mind that they were using ethical factories.

The truth, as Mohsin explains, was murkier. “Sustainability comes out of cost… but the likes of the companies that are making it… won’t pay for it! They’re like, ‘We’re going to order 400,000 piece of a garment, but we want full transparency of where it’s come from… but I still want the garment for $16.”

Even as retailers and buyers jumped on the ethical/sustainable bandwagon, forcing their suppliers to do likewise, they refused to pay a premium for the same advancements they’d foisted on the Bangladeshi makers.

Despite marked improvements to factories; things like water treatment plants, adequate lighting, and manageable shifts, factories must work overtime to keep the lights on. “Most of these factories,” Sajid explained, “Run 24 hours a day. So they’re not a 9-to-5 like they are in the western world, so they’re constantly pumping out stuff.”

Demanding that Bangladeshi factories upgrade their facilities was a huge win for workers, but a bigger win for retailers. Now, a brand can technically say their product is made ethically and their factory must comply—without proper recompense.

The so-called “race to the bottom,” the option to manufacture for ever lower prices, makes it hard for Bangladesh to compete, especially as cheaper, less-regulated labor options become available in places like Ethiopia. As the accords from 2013 begin to expire, Bangladeshi factory-owners seek more autonomy in the auditing and regulation process. But one such independent Bangladeshi evaluator called Nirapon was suspended by the country’s Supreme Court at the behest of an influential industry-member.

Sustainability and worker quality-of-life might keep western customers complacent, but they’re costly measures that few want to pay for.

Cancellations in Bangladesh

BROWN LIVES MATTER – BUT CLEARLY NOT TO ARCADIA, PEACOCKS & LI&FUNG/GBG:This week I spoke to @wwd

It is amazing how many brands have been quick to virtue signal over the issue of Black Lives Matter.

But what about the brown lives of workers in their supply chains?@fashionkales pic.twitter.com/5POpcy4M0y— Mostafiz Uddin (@mostafiz_uddin) June 24, 2020

The fragile ecosystem of Bangladesh’s garment industry never stood a chance when the cancellations came. The push and pull of the industry’s various actors: foreign and domestic, retailer and supplier might have reached a delicate stasis, but with completed orders suddenly canceled, it all came crashing down.

Though large cancellations devastated the industry, few spoke out, fearing retaliation from negative publicity-phobic retailers. One of the few to speak out was Mostafiz Uddin, owner of the jeans maker Denim Expert Inc.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Mr. Uddin shared his correspondence with Li & Fung, a buying agent for major fashion brands who’d been refusing to pay, “You may have thousand problems [sic], I do also have millions of problems too!” In his conversation with the WSJ, Uddin totaled up at least $700,000 in two unpaid orders, but the total may be much higher and what’s worse, the retailers may even sell the as-yet un-purchased merchandise.

Sajid, who’s consulted with Uddin, elaborated, “Most of his business is with high street, that’s how he’s set up… but because of that, the likes of Topshop, Peacocks, and Arcadia, they’ve just refused to pay him. They’ve even accepted all the goods. They’ve even accepted it into their warehouse, for instance, and they’re not going to pay him.”

Uddin, despite the standstill in cash flow, managed to scrape together the resources to pay for his employees’ salaries for 100 days, as well as the customary Eid-al-fitr bonus for the holidays.

Unfortunately, not all factory-owners share his scruples: more than 2 million garment workers have been laid off in Bangladesh alone. With buyers refusing to even reimburse the factories for the raw materials used in their orders, there is no money left to spare, affecting consultants like Mohsin as well.

Mohsin Sajid is good-natured about the payments he’s waiting on, but he paints a dire portrait of life for laid-off garment workers.

I’ve been to factories where it’s a compound. And where they work is only a few meters away from where they live and they’ve got their family in that little room—kids and mum and everyone in that one room. So when you hear about [factory owners] can’t pay [their] workers, it’s actually much worse. Because that one guy he’s paying is probably supporting his family and he’s supporting his grandparents and his immediate family.

From boardrooms all the way down to the living quarters of factory compounds, the decisions to back out of agreements will affect not just the men and women who work in factories, but their families as well.

Greater Good?

Clothes in landfill. Image via the Guardian.

There are no winners in the Bangladesh debacle. Though Bangladeshi businesses may wrest themselves from western control, it may be to the detriment of the worker quality-of-life or, if these same businesses commit themselves to truly ethical and sustainable manufacture, the western buyers may simply turn up their noses and go somewhere cheaper. Forcing buyers to pay off their suppliers might help workers abroad, but could harm employees at home.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction, the supply chains, agreements, and accords have become so convoluted, there is no way simple way to resolve the mess.

When talking to Blake Ulves about the situation, his response was more expansive than I had anticipated.

Should we feel sorry for these businesses or should we chalk it up to a capitalistic market that is maybe correcting itself? Maybe this is the market saying, “Hey, we’re too inefficient in the world right now, right?” We’re supplying way too many clothes and people are buying this crap all the time. It’s low quality, it’s damaging the environment, and maybe this is just how the market corrects itself.

And the people who fail were the ones who weren’t efficient and weren’t contributing well to the market… does Bangladesh really need to be pumping out millions and millions of tees that go to H&M, which will go to the closeout racks, which will eventually be sold off to jobbers, and sent to a third world country, because no one ended up buying them. And then the next day, they’re in the landfills, they’re in the ocean…

The uncomfortable truth is that the fashion industry, as it currently operates, is untenable. Not only that, it’s inhumane. Fast fashion is a race to the bottom, to carve out the widest margins from the wages of people up and down the supply chains. For every good actor keeping their employees paid while business has stopped, there are just as many (or more) working to exploit the systems in which they operate.

Unfortunately, much talk of ethics and sustainability are purely for show. A Topshop executive might take to social media, to brag just how well-intentioned their new line is, but if it isn’t immediately evident in the price-tag, someone is losing somewhere.

It is hard to conceive of a future that doesn’t somehow disenfranchise those on the lowest rungs of this rickety ladder, but Covid has once again made clear that the status quo simply doesn’t work.

If the recent string of high-profile bankruptcies is any indication, these buyers and retailers may be due for their comeuppance. Unfortunately, the fates of these oft-cruel companies are inextricably tied to the paychecks of people we know, like consultant and educator Mohsin Sajid, and those we don’t, working in many factories around the world.

We must hold these corrupt institutions accountable for their actions and we must look inward and assess our own values, the next time we find a sale coupon in our inbox.