In modern times, we tend to fetishize the stalwarts of American manufacturing: those heritage mills and companies that stuck to their guns through thick and thin. These factories have weathered world wars, economic downturns, and all manner of catastrophes—and though many of the great mills were shuttered in the 1980s-90s, their rich histories bear examination.

History, after all, doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Though we uphold these mills as bastions of a great American tradition of independence and entrepreneurial spirit, these same factories (mostly located in the South) are complicit in some of the darkest moments of our national history.

These American institutions have been accomplice to segregation, Jim Crow, and the overall disenfranchisement of Black Americans. This attempt to preserve “whiteness” not only subjugated Black people, it made unionization nearly impossible and by race-baiting, factory owners managed to subjugate white workers as well.

“Psychological Wage”

In 1915—the same year that Cone Mills and Levi Strauss & Co. formalized their partnership with the legendary “golden handshake”—the South Carolina State General Assembly signed into law what would become commonplace across the burgeoning Southern textile industry: segregation.

Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, That it shall be unlawful for any person, firm, or corporation engaged in the business of cotton textile manufacturing in this State to allow or permit operatives, help and labor of different races to labor and work together in the same room…

Until well into the 1960s, Black men and women could only work in textile mills as “mill laborers” a catch-all position that typically included the hardest and most back-breaking work—and at a fraction of a white worker’s wages.

Just because it was only set down on paper in 1915, doesn’t mean it didn’t exist before. In 1886, Henry Grady, an editor for the Atlanta Constitution, announced the coming of the “New South.” The post-abolition South might no longer have had slavery, but the measures used to keep the newly-liberated Black people down simply became more subtle and insidious.

Liberated slaves were oftentimes skilled craftspeople and artisans, but instead of opportunities to ply their trades, they were forced into tenant farming, a condition that closely resembled their lives in bondage. For poor white Southerners, the New South posed some difficult moments of self-reflection. White supremacy had been predicated on racist beliefs that African-Americans were inferior and destined to lives in slavery.

When slavery was removed from the equation and poor white workers found themselves in the same jobs as freed Black people, their identities and conceptions of white supremacy were threatened.

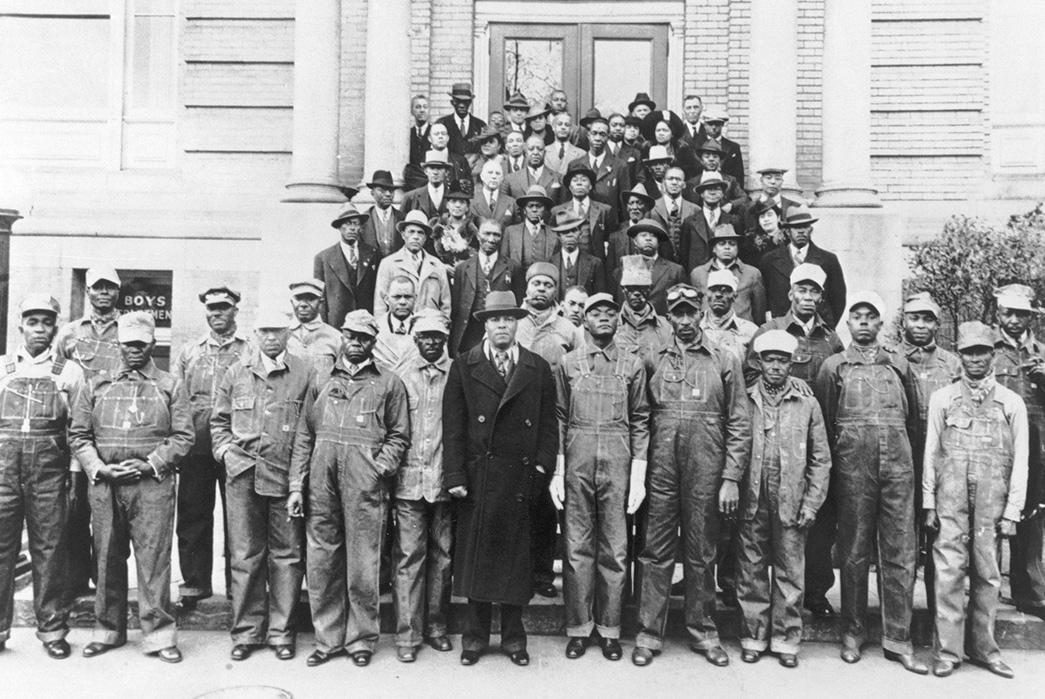

Image via History in Photos.

The nascent textile industry proved a way to remove poor whites from a workforce in which they were beginning to find themselves competing with Black workers. Southern boosters, eager to bring economic growth to their region, touted industrialized textile mills as a matter of regional pride and mill towns sprang up: little white supremacists utopias.

These mill villages operated under a paternalist system, in which, in addition to their wages, white workers were provided room, board, and a number of amenities.

In the 1930s, mill villages in Georgia had access to indoor plumbing, electricity, and were paid wages markedly higher than their counterparts on rural farms. The mill villages had movie theaters, baseball fields, and paid whites what civil rights activist and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois referred to as, “the public and psychological wage.”

This psychological wage was and remains the crux of white supremacy. It separates the “us” from the “them” and reinforced the misconception of destitute whites that they were somehow better than their Black peers. The trappings of modern life, which were difficult to attain in rural part of the South helped reinforce poor whites’ sense, that even though slavery was formally abolished, they still had a leg up on Black Americans.

In the early 1900s, to work in a textile mill, was to insulate oneself from Black people and regain the false feeling of superiority that had sustained poor, uneducated, non-land-owning whites during slavery. Mill owners, by coddling and spoiling their white employees and keeping what few Black people they encountered in demeaning positions at the mills, paid white workers this intangible wage—white supremacy.

The Times They Are A-Changing

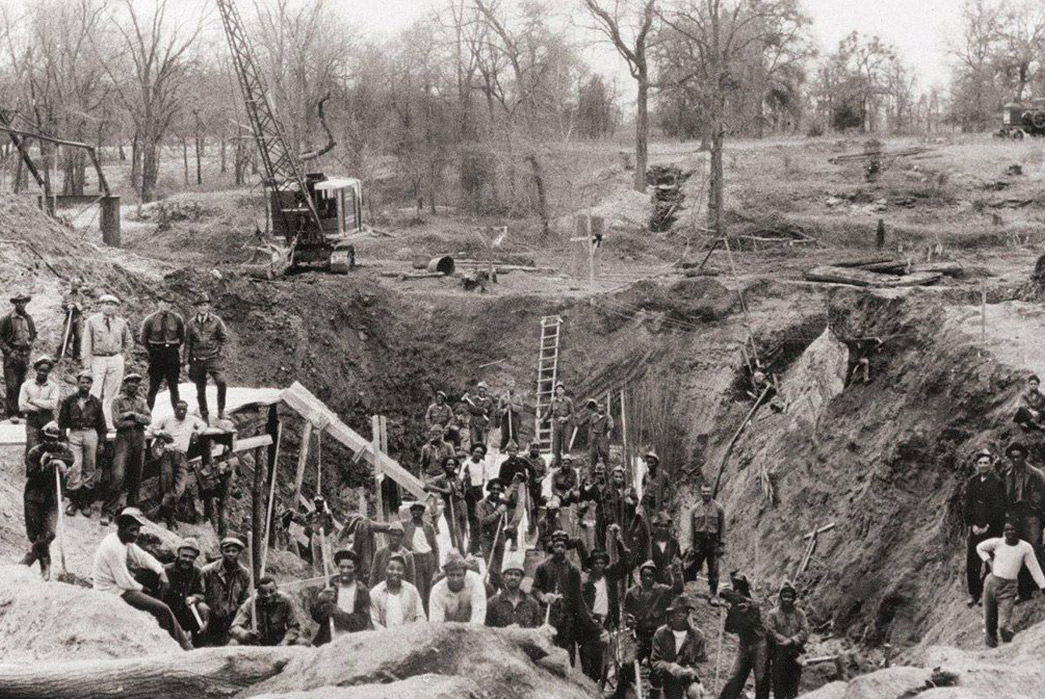

WPA workers. Image via KTWX.

The road to integrating America’s southern textile mills was long and arduous, but many historians make the story’s main players into passive characters. The criminally-simplified version goes: paternalist mill owners convinced poor whites to vote against their best interest and stoked racist sentiment and eventually, when labor was distributed differently, Black folks eventually found work in mills, because they were needed there.

This version of the story doesn’t give much credence to the active efforts of whites to fight for and maintain their supremacy, nor does it give credit to the brave Black activists and organizers who fought tooth and nail to gain access to employment in mills.

Before 1940, only one in ten mill workers was Black—and 80% of those Black positions were as “mill laborers,” that aforementioned catch-all that mostly meant more work and less pay. But by 1978, one quarter of all mill workers were Black, not just laborers, but proper employees.

The first break in the wall of segregation came to the South during the Great Depression. The National Recovery Administration undertook massive infrastructure projects to get Americans back to work, but white Southerners took issue with this. This progressive enterprise hired Black men and paid them a higher wage than whites earned in their jobs in the textile mills, which mill-owners purposefully kept non-union.

During the Great Depression and later on, during World War II, the long arm of the federal government reached into the previously-impregnable kingdoms of the mill-owners. In 1935, the National Labor Relations Act was written into law, and though ultimately it didn’t contain a clause against racial discrimination by unions, many of the unions who underwrote the law already had vocalized their support for Black workers in their unions.

Southern employers were further pressured by war-time production standards, including the Fair Employment Practices Commission.

By withholding wartime contracts, the Federal government leveraged its power against the textile mills, allowing permanent unions to form and in some cases, giving better jobs to Black workers. But there was much dissent when then unions’ talk turned toward race. White workers became further embittered, those who rejected unionization and wartime federal intervention risked receiving markedly lower wages than their Black counterparts in other industries.

The unions that did find success in the South, usually did so by cloaking their long-term goals of integrating the work-f0rce and appealing across class lines within white communities. But without confronting whiteness, the unions of the 40s and 50s may just have politicized white supremacists, ultimately making them more organized and harder to beat.

The New New South

Image via Center for American Progress.

Unlike white workers in mills, the Black “mill laborers” were becoming jacks of all trades. As mechanics, loom-cleaners, and sweepers, Black laborers became intimately familiar with mill machinery on a more profound level than whites who had a more specialized job. A white worker was expected to remain at their post all day, but Black workers, with their higher workload were paradoxically learning more and becoming better qualified candidates.

Nevertheless, as the Civil Rights Movement began, the language of racism changed. In place of blatant racism, came an emphasis on “qualifications.” This veiled effort to discriminate against Black candidates was absurd, especially given Black mill workers position as “industrial observers.” Black mill laborers, before 1965 were almost never promoted, but on the off-chance they were, they were almost certainly pre-trained in whatever new task they took on.

Change had to come from the outside. Long portrayed as benevolent, the mill owners took a rather laissez-faire approach to integration and only when the Federal government applied significant pressure. Before the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) attempted to make inroads integrating the major Southern textile mills.

By 1953, Cone Mills had two fully integrated departments, although the AFSC recorded that the mill’s owner, Herman Cone seemed hesitant to integrate the rest. Cone, as well as the owners of other prominent mills argued that their uneducated white staff would never accept integration and therefore, that management’s hands were tied.

Historians take turns laying the blame on mill-owners and mill-workers, but the truth (as is often the case) is somewhere in the middle.

Interracial unions had long served as a boogeyman with which to control white workers, who likely would receive better pay and benefits with a unified and integrated union. Integration would also make Black workers’ unofficial positions official. Some reports, as told in Mary Frederickson’s Four Decades of Change: Black Workers in Southern Textiles, found that white workers trained and paid under-the-table bonuses to Black workers who took on more complex jobs in the mills than their designated “mill laborer” status would have allowed.

Various mills, in various states took drastically different approaches to the treatment of their workers, but nearly all responded to integration with some amount of reprobation.

Ultimately, it was a deluge of lawsuits filed under title VII of the Civil Rights Act, “the equal employment opportunities clause,” that blew open the doors of the textile mills. Suits like Lea v. Cone Mills Corporation, filed in 1969, finally allowed for full entrance into the textile mills, especially for Black women, who had been given the least opportunity.

In this particular case, the court found Cone Mills guilty, “The defendant has intentionally engaged in, and continues to intentionally engage in, unlawful employment practices at its Eno Plant with respect to the employment of Negro females.”

It was not, as so many historians have alleged, that white workers simply moved up in the world in the 1960s and left the mills under-manned and open to Black labor. Rather it was the vested effort by Black workers to break into an industry that could afford them a better life.

All Too Late

A shuttered textile mill in North Carolina.

Though the American textile industry of the 1970s and 80s proved far more accepting, it was already too late. By this time, many American brands had begun outsourcing and huge chains like Gap and J.C. Penney had moved the majority of their production overseas.

By the time that Black workers came to represent over a quarter of textile jobs in the South, the boom was over. Though the battle for integration was won, the larger war was lost.

This fight for equal employment in Southern textile mills parallels the golden age of American garment production, but it’s uncommon that we associate this history of white supremacy with our favorite vintage clothing. We are, of course, still allowed to love those Cone Mills Levi’s from the 40s and 50s, but we must acknowledge that they were woven in segregated and unfair conditions.

As we reckon with systemic racism in our lives today, we must also reckon with its hold on our ancestor’s lives—and yes, even on their clothes. We, lovers of Americana that we are, must remember that which represents the very best of what is American can doubly represent that which is most unjust.