I recently got back into projecting film. I was the kid in college that had a couple of 16mm projectors (that accompanied my typewriters and cassette tapes). I would host movie nights where unsuspecting viewers would be subject to multiple intermissions that often added up to longer than the run time of the movie itself.

There are many reasons not to watch movies on film. A two-hour feature fills up about 4,000 feet of 16mm film, which has to be stored on at least three separate reels. So after you finish with the first, it has to be rewound and put away before the next one is threaded back through the machine and fired up again. This process takes at least five minutes, even for the very skilled.

Almost all 16mm prints are very old—they were really only in circulation before VHS tapes became popular in the late 1970s—so most of them are fragile and somewhat degraded. Many prints were made of cellulose acetate (just like sunglasses) but after half a century, they smell like vinegar and everything looks slightly red.

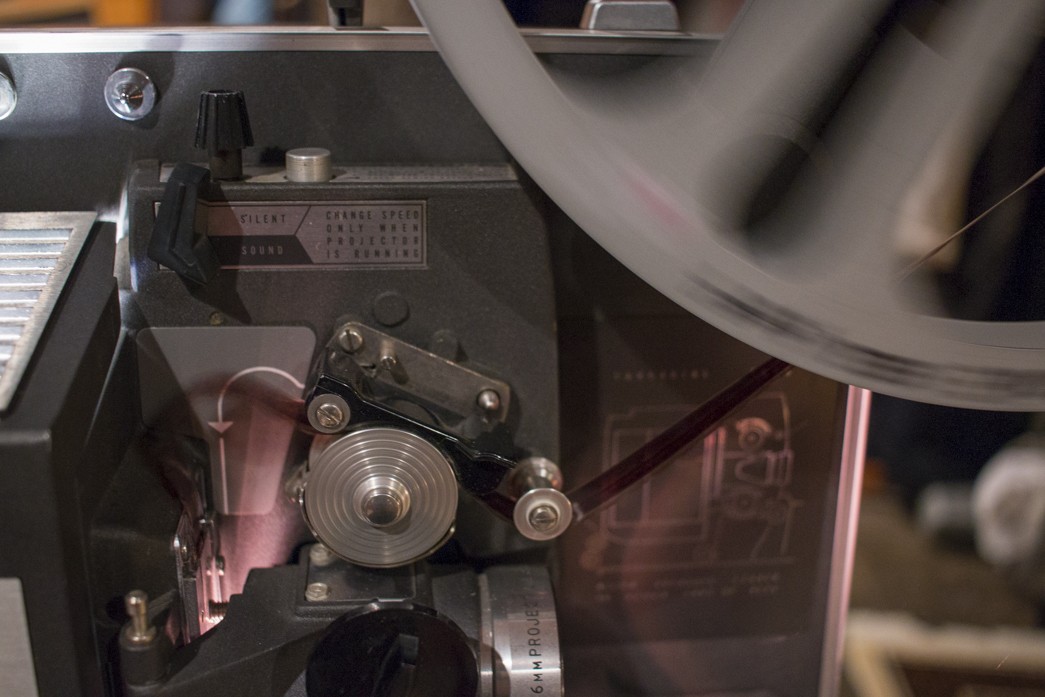

This thin piece of plastic is flying through the projector at tension and it occasionally breaks, at which point you have to overlap it on the perforated holes and tape it back together and then rethread the thing and hope it holds.

And because film is old and uncommon it’s also expensive. A watchable print of any movie you’ve ever heard of runs at least a hundred bucks on eBay plus more for shipping, as they weigh about 15 pounds.

But I love film regardless. The functioning of even a now antiquated DVD player is completely beyond my comprehension, but with film, you can pull the celluloid out and almost watch the movie by looking at the individual frames. You can see the waveform on the edge that makes up the soundtrack. There’s no “magic” in it, it’s a tangible and immediately understandable format.

Anthony Quinn in red.

An ex ended up with one of my projectors, my film professor the other, but I held on to a vinegar-red four-reel print of Guns of the Navarone in the hopes that I would one day view it again.

Last weekend, I found a Bell & Howell Filmosound on craigslist, the same kind I had in college. I drove two hours and paid $60 for it. When I got home, I threaded up the first reel of Navarone and as the film rattled through the projector like a detuned lawnmower and the room heated up from the stupidly powerful lamp bulb, I was happy to welcome this old print back to life. And soon (hopefully soon), a new group of friends will be subjected to their own interminable movie night.