While the notion of child labor still strikes a chord for us, for many people lucky enough to live in stable, developed countries, the concept sounds like a punch line—something too alien to comprehend. At least in the United States, child labor is almost exclusively a thing of the past.

But the process of banning child labor in the U.S. was an extremely difficult one, only made possible by significant changes in public opinion and savvy politicking.

Today, in our continuing series of Labor Rights History, we discuss the fall of Child Labor in the United States: why it was so difficult to permanently vanquish and some serious loopholes in the law that keep approximately 500,000 underage children working even today.

The Child as Property

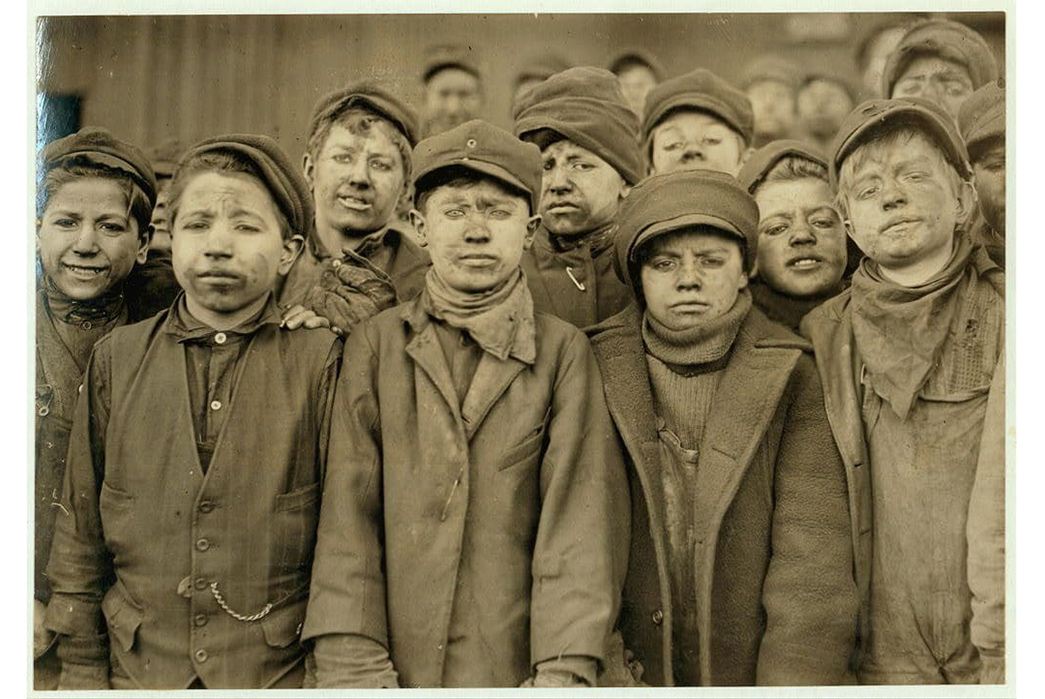

Hines picture. Image via Library of Congress.

In Michael Schuman’s History of Child Labor in the United States, he cites a 1906 article in Cosmopolitan magazine which told the story of a Native American chieftain’s first trip to Manhattan. Brought from a more rural setting to the bustling metropolis, when asked by the interviewer which of the sites most shocked him, his answer was unexpected, “little children working.”

Children, of course, had always worked. Early human hunter-gatherers had enlisted the help of their children in obtaining food and supplies and later in more developed societies, children had often worked as apprentices or servants, usually learning a trade. In England, for example, there was much concern about the so-called “idle child,” that working class children who weren’t fully engaged in some form of work during the day would grow to become unproductive and useless.

This closely aligned with the Puritan belief that work was the surest way to ensure one lived a moral life, you know “idle hands are the devil’s playthings,” etc.

Beyond that, children were economically valuable for their parents. Farmers eagerly anticipated the birth of new children who could grow up to serve as labor and keep things running smoothly—and this also became true in urban environments as the Industrial Revolution began.

Since the 1700s, laws in England and the U.S. had considered children the property of their parents (typically fathers) and oftentimes when a child died at work, the parents could sue for restitution, based on the wages that the child would have brought home in their lifetime.

This is large in part due to the fact that children passed their income onto their parents, and were usually only allowed a small allowance of what they earned. Children’s labor often accounted for almost a third of the household income, because it was uncommon for women to work outside of the home at the time.

However, the entire pitch and tone of children working changed with the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s. This cold and calculated view of children as mere units of economic output would only grow harsher with the introduction of an entirely new style of manufacturing.

Children and New Kinds of Work

Lewis Hine’s photo of a young spinner. Image via Washington Post.

The Industrial Revolution was a shock to the manufacturing status quo, totally disrupting the world’s economy. There was much that this period changed, but few things were so inextricably altered as the role of children in the workplace.

A new kind of mechanized work needed more warm bodies to man machines and often this workforce didn’t need to be especially skilled.

Young doffers. Image via Washington Post.

It sounds like a cliche, but child labor was actually necessary because of the children’s small size. They could get places inside machines where adults couldn’t reach and perform tasks that were too menial or challenging for someone with an adult’s dexterity.

In some cases, these tasks required small children’s hands, as was the case in glass bottle production, where children’s hands were needed to polish the inside of glass bottles and in other, even more grueling industries like mining, many young adults’ hands were already too warped and broken from the labor to perform small, delicate tasks, so again children were needed.

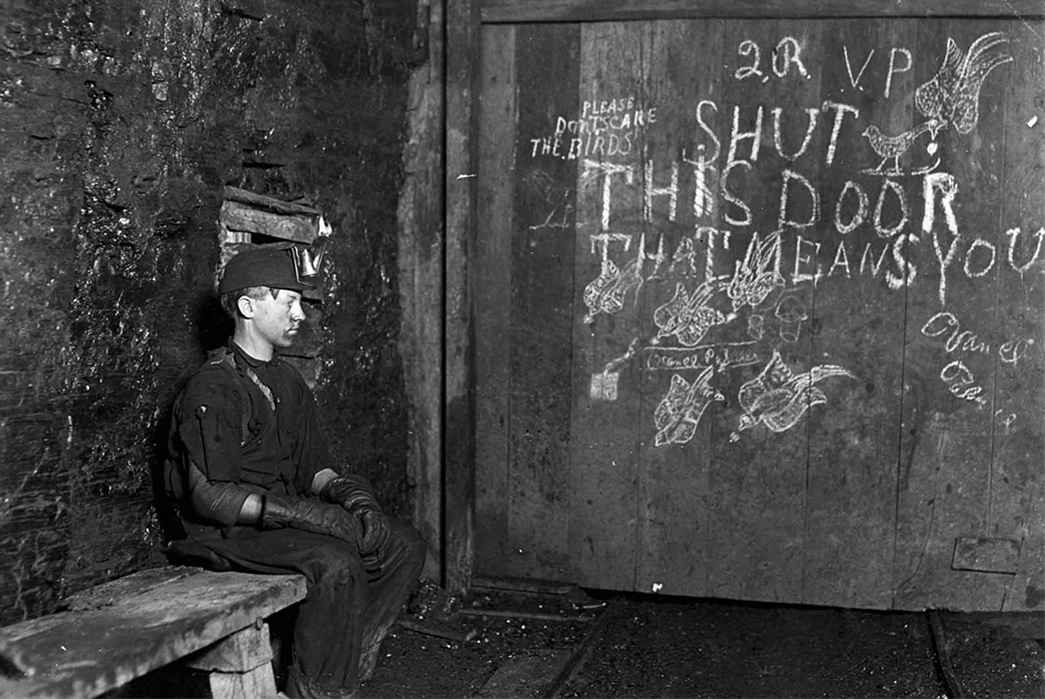

Vance, a trapper. Image via Library of Congress.

Children were also more tractable and could be persuaded to do work that no one else wanted to do. Take for instance the trapper, shown above. The trapper worked in a coal mine and his sole job was to open and close the door that allowed the mine cars to exit the mine.

These doors were a crucial part of the ventilation system and needed to be opened and closed periodically to let in and out air. But when the child trapper wasn’t working, he was sitting in complete or almost-total darkness. This particular child’s name was Vance and he was paid 75 cents for a ten hour work-day, most of which was in pitch black.

Giles Newsom and his injured hand. Image via Library of Congress.

Not only were the children paid paltry sums, which usually just went to their parents, they were at high-risk for injury. Giles, the boy above, was only eleven when he severely injured himself in the spinning mill in which he worked. A piece of machinery fell on his foot, crushing his toe, which caused him to reach out and fall into the spinning machine, which then ripped out two of his fingers.

Many employers who used child labor argued that by employing these minors, they were lifting them and their families out of poverty, but the truth was obviously more complex. Children were impossible to unionize, they were easily manipulated, and they could be trained for a lifetime’s toil in the same facility by starting them early.

Reform

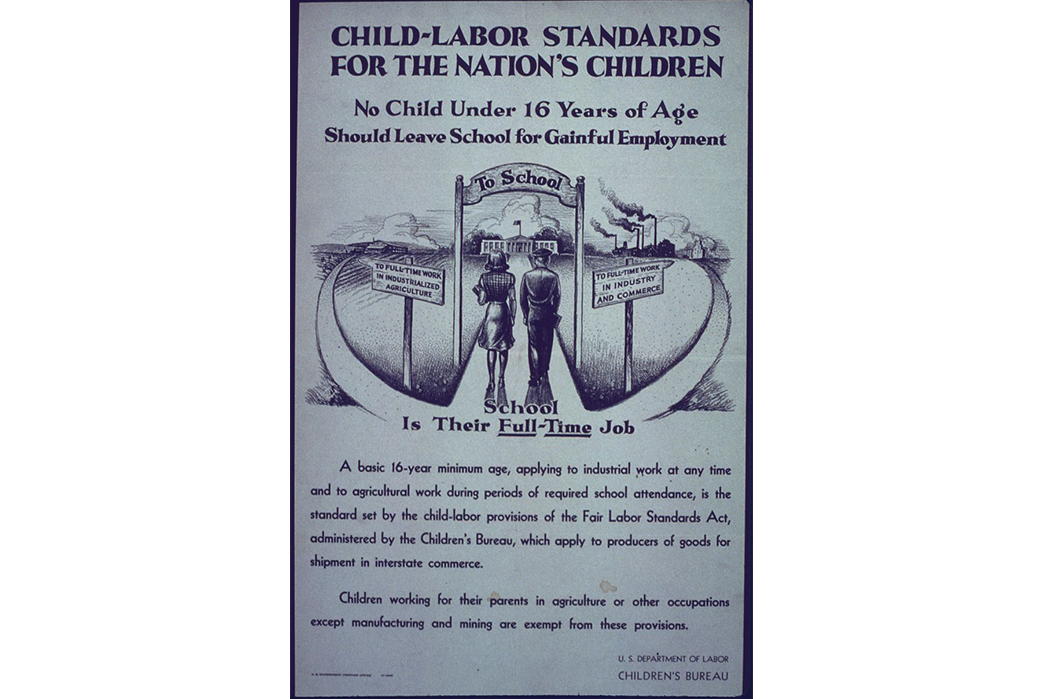

Image via Wikipedia.

The 1900 census found that nearly 1 in 6 children was engaged in some form of gainful employment, a statistic that shocked Americans. Four years later, in 1904 the National Child Labor Committee was formed as an amalgam of several smaller anti-child labor groups.

The foundation of the NCLC coincided with an era of unprecedented social activism called the Progressive Era, this period of time around the turn of the century would result in a number of important changes in American society, women’s suffrage and prohibition being some of the best-known.

The early 1900s also coincided with a booming American economy, an economy that needed huge numbers of unskilled laborers to keep up production. While Americans became more and more concerned about the role of children in factories (children in agriculture was still considered natural), change was slow in coming.

The NCLC effectively broke into two halves to focus on Northern and Southern states, launching a huge campaign that included investigating working conditions and lobbying legislators, but one of the greatest coups won by the organization was hiring a man named Lewis Hine.

Lewis Hine’s shocking photograph of Frank, a 14 year old mine worker, whose legs had been crushed by a coal car. Image via Library of Congress.

Hine was a sociologist and teacher, whose skill with a camera was a huge boon to the anti-child labor cause. Without internet or any form or rapid communication, it was hard, in the early 1900s to prove that the stories of children working in terrible conditions were even true.

After all, it was very common, in this period for kids to work—newsboys, shoeshiners, etc. were more or less accepted and it was hard to comprehend the injustices of child labor that happened underground in mines or behind closed doors in factories. When questioned, factory owners basically explained these rumors away as “fake news,” so to obtain actual photos of the children and their working conditions rocked the country.

Hine, whose photos make up all the pictures used in this article, posed as a bible salesman in order to gain entry to the factories. His work took place around the time newspapers first began including photos on their pages and his interviews with children about their ages, work hours, and lives were highly incendiary. Hine found children permanently stunted by their labor—physically from toil and injury and mentally, by lack of education and play time.

As popular support mounted, the American Department of Commerce and Labor founded its Children’s Bureau, but there were legal issues yet to come. From 1915-1917, a number of efforts were made to eliminate children from working in dangerous industries, but despite their popular support, they were found to be Constitutionally unsound.

The first law passed in Congress was the Keating-Owens Act, which prohibited the sale in interstate commerce of goods made by children under a certain age threshold or who had to work an unreasonable amount of time today, but this, like other acts, was struck down by the Supreme Court. The Constitution may give the federal government the right to regulate interstate commerce, but many traditionalists didn’t think the feds could regulate working conditions.

The NCLC then attempted, in 1924, to pass an amendment to the constitution, which would allow congress to regulate the work of people under age 18, but this amendment is technically still pending and never got support from the requisite number of states.

It wasn’t until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed and signed into law by FDR. This Act guaranteed a minimum wage, overtime, and prohibited the use of labors in oppressive labor.

All that being said, the legislature of anti-child labor laws may mostly have been due to circumstance. There was a huge popular movement to get children out of factories and into schools and to protect workers from dangerous conditions, but child labor in the U.S. was only at its peak when the Industrial Revolution was in its earliest phases and the American economy was very strong.

As time wore on, the machinery in factories became smarter and more-efficient and required less supervision and when the Great Depression hit, all available jobs were needed by adults and there was simply less room for children in the workplace.

A more cynical take on the end of child labor in the United States was that it was no longer as profitable or sensible to employ children and consequently there was significantly less corporate pushback on congress.

Child Labor Today

Child Worker in a North Carolina Tobacco Field. Image via Human Rights Watch.

Today, laws vary somewhat state-to-state on how old one must be to work, but these laws are especially lenient in agriculture. Under federal law, children under the age of 12 can work unlimited hours in agriculture with a parent’s permission and children over the age of 16 can be employed in hazardous industries.

The myth of the wholesome family farm has caused a legal blindspot in the United States. People are horrified when they find out children made their shoes in a sweatshop somewhere overseas, but are not so stunned by the idea of children making and growing their food.

Half of work-related child deaths in the U.S. happen in agriculture, but this number may be even higher if we consider that many people working in food production in our country are undocumented and their injuries and employment go unreported. Just as in the 1900s, children might falsify their age to obtain work and help support themselves and their families.

The Trump administration has attempted to even further roll back the very meager protections set in place for child farmworkers, who are already at much greater risk of injury or death than young people in almost any industry.

Great strides were made to protect our nation’s children, but the cynics among us could argue these changes were only made when it was economically convenient to do so. Regardless, forward progress in protecting the most vulnerable people in our society does not come easily and we need to be mindful of forces that seek to undo it.