77 years ago, the goings-on in downtown Los Angeles were uncannily similar to those today. A combined military and police presence had taken to the streets and much as they are today, they were on the hunt.

American sailors and marines in early 1943. Via Getty Images.

Beginning on June 3, 1943, several infamous days of riots, now known as the “Zoot Suit Riots” erupted in Los Angeles. The name of the riots is misleading and while it seems to suggest that the predominately Mexican-American youths wearing the distinctive zoot suits were the aggressors, they were, in fact, the victims.

The Zoot Suit Style

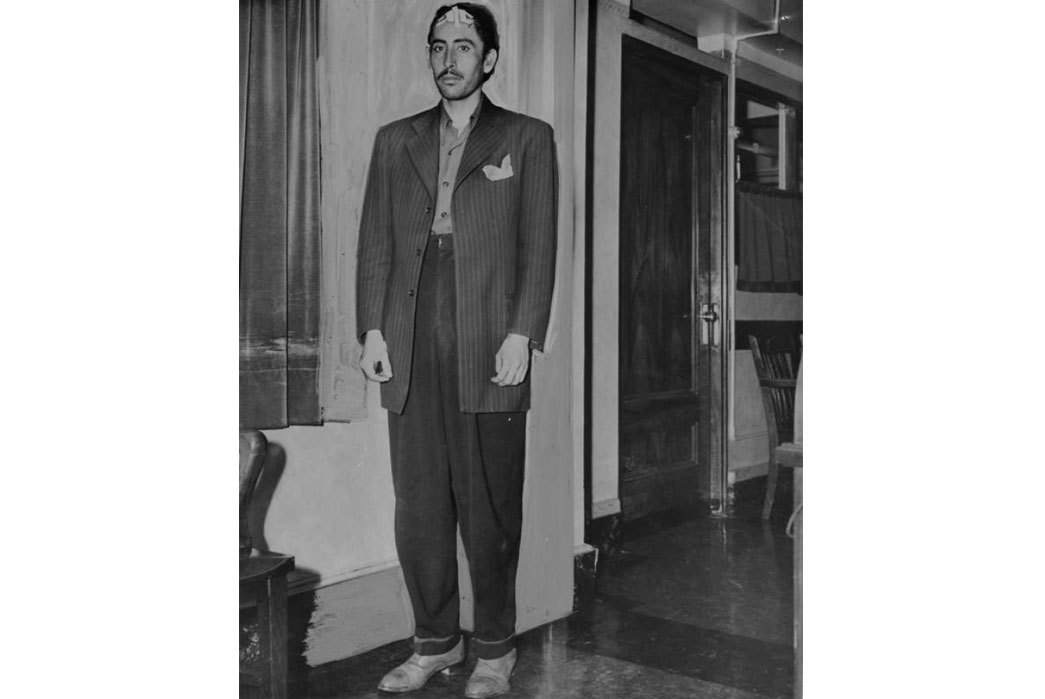

Luis V. Verdusco, June 3, 1943. Image via Los Angeles Public Library.

In the early 1940s, the U.S. was at war and with its fighting men abroad or in training, women and people of color gained access to jobs that had previously been inaccessible to them. Despite Jim Crow laws and general racist sentiment, the massive reduction of the white workforce caused an influx of disadvantaged peoples into these once white-held jobs and wartime manufacturing and its accompanying jobs were a boon to Mexican-American communities in many Western states.

Increased buying power for Mexican-Americans meant more opportunities to experiment with style and in the early 1940s, there was nothing quite so hip and bombastic as the zoot suit. Adopted from the similarly baggy “drape suits” worn by black Jazz legends in Harlem, the zoot and drape suits (like jazz) rejected normative white standards, and tacitly, segregation.

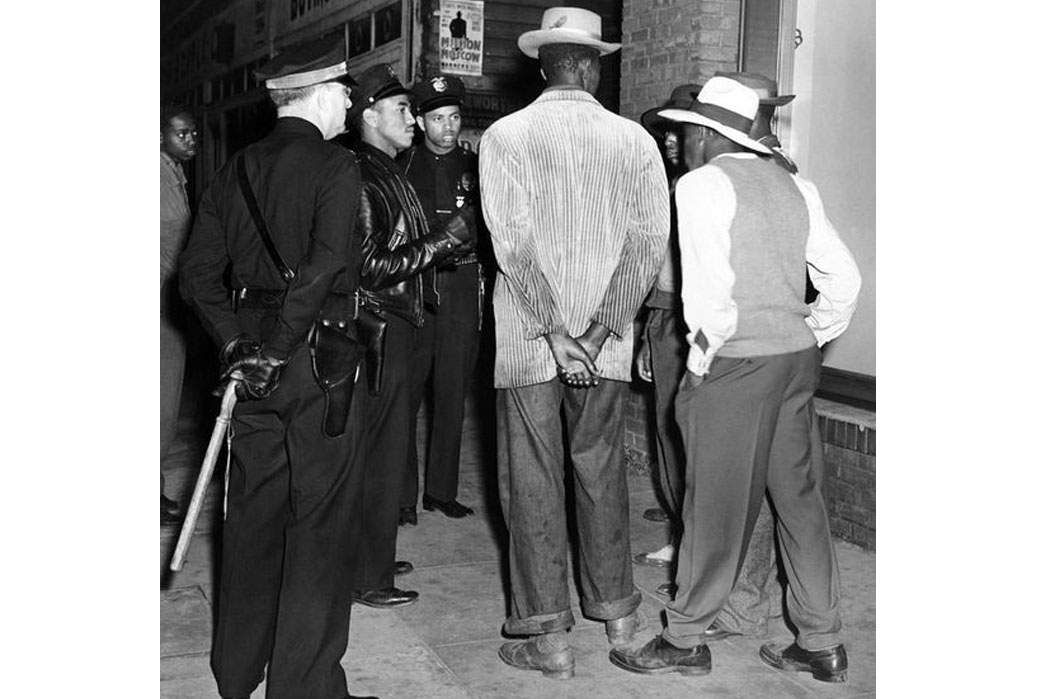

Black zoot-suiters, 1943. Image via Fine Art America.

The suits had long jackets, often cut from luxuriant, brightly colored materials, and deeply pleated pants. Wide, padded shoulders tapered down to narrow, pegged trouser bottoms and wallet chains and leather shoes added some extra flair.

But getting a zoot suit wasn’t necessarily an easy feat, especially during WWII. Many consumer goods were rationed in the 1940s to help the war effort and fabric was a significant part of that rationing—so much so that men’s clothing slimmed down tremendously in the period (see the difference in pre- and post-war 501s). Where bulky, drapey clothes had once been considered largely tasteful by white America (you can’t see anyone’s junk in a heavily pleated pair of pants), changing mores during the war made zoot suit-wearers a target of white American ire.

Though all non-white communities in Los Angeles faced intense discrimination in the early 1940s, there was a particular bias against Mexican “pachucos.” The August 1942 “Sleepy Lagoon” murder quickly leveraged the full force of the LAPD against Mexican-American youths. A man named Jose Diaz was stabbed to death near a popular swimming hole in modern day Bell, in southeast LA, but instead of investigating, the police rounded up 600 Latinx youths and tried 22 for the murder.

At the Los Angeles County Hall of Justice (where protestors are currently demanding District Attorney Jackie Lacey’s resignation) the presiding judge, William Fricke didn’t allow the arrested men to change their clothes or hair, thus cementing the association of their dress and appearance with the Mexican criminal stereotype.

The “Riots”

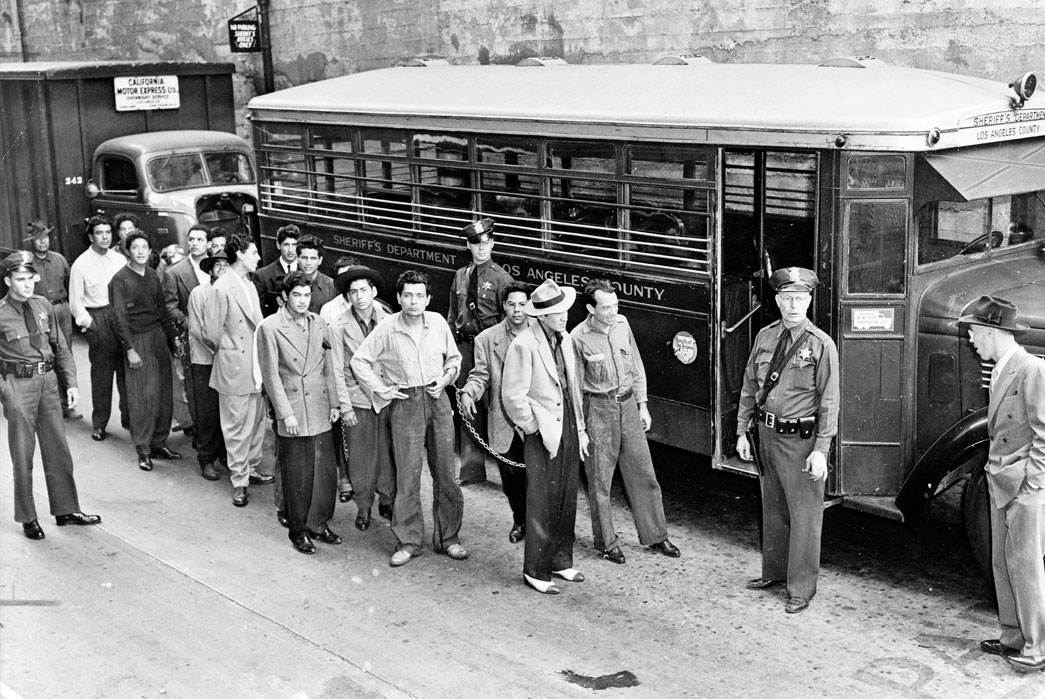

Supposed “ring-leaders” of the “riots” brought in for questioning. Image via LA Public Library.

Just how the riots began is unclear, but starting on June 3, 1943, racist sentiments boiled over among the Navy and Marine servicemen stationed in LA. The focal point may have been in the Chavez Ravine, a historically Latinx neighborhood that has since been buried beneath the sprawling parking lot of Dodger Stadium. At the time, sailors were being trained in the vicinity and various sources tell of some kind of confrontation between Navy men and zoot-suit wearing pachucos.

An LA Times article released on June 3 levels all manner of racist claims, including “Juvenile files repeated[ly] show that a language variance in the home – where the parents speak no English and cling to past culture – is a serious factor of delinquency,” among others. But the article makes reference to “organized bands of marauders, prowling the streets at night,” likely referencing Latinx youths, when nothing could have been further from the truth.

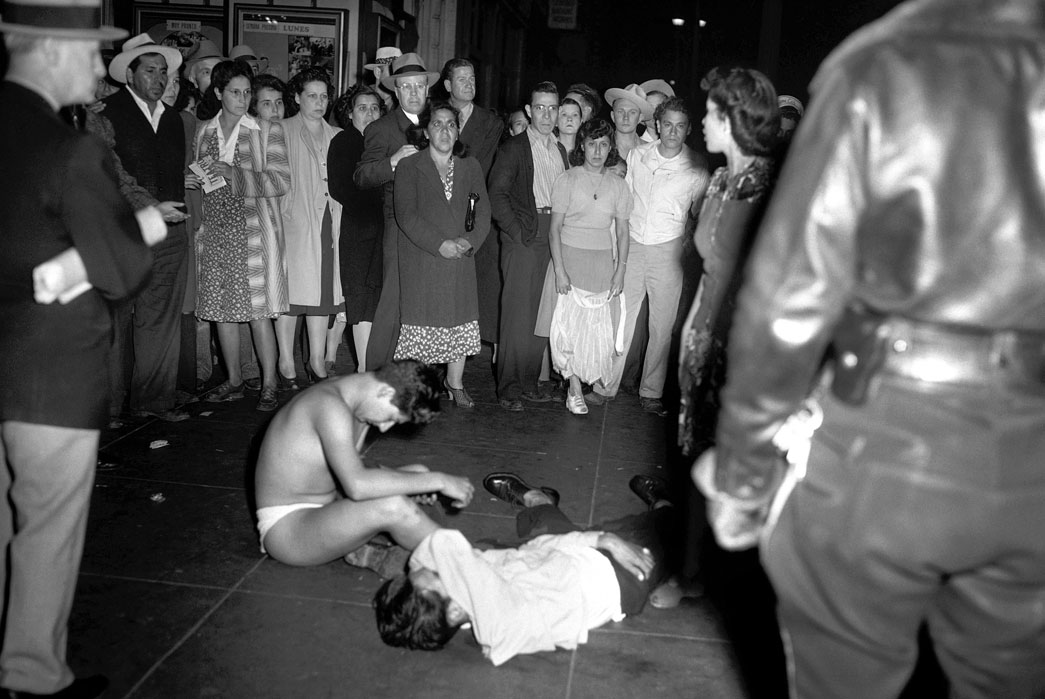

Youths left beaten and stripped by servicemen. Image via AP

Whatever transpired between servicemen and zoot suit-wearing Mexican-Americans in the Chavez ravine, the story that reached the barracks was blown entirely out of proportion. The LAPD was quick to arrest pachucos named by sailors, but sailors still fashioned clubs and grabbed baseball bats, and chartered cabs to far-flung Hispanic neighborhoods of LA.

They raided Spanish language theaters in Downtown LA, they went to Boyle Heights, and deeper into Southeast LA, targeting men in zoot suits. Latinx folks resisted the attacks, but were beaten and arrested in huge numbers and servicemen indiscriminately attacked black and Filipino people as well, with no motive but hate.

Arrested Latinx men. Image via AP.

Despite the arrival of the LAPD and military police, the beatings continued and more arrests were made. Unfortunately, the majority of these arrests were the people who’d been targets, not instigators. Though no one died, teenagers as young as 15 were left in the hospital with injuries from the attacks, including gunshot wounds.

It was only when the military police banned servicemen from leaving their bases and coming into the city that the violence stopped.

LA Today

LAPD begins beating a crowd of protestors. Image via LAist.

It is a strange twist of fate that the anniversary of this violent period would fall now, as Los Angeles reels under the grip of a violent police force, stringent curfew, and National Guard occupation. Protests, which sprang up in response to the police killings of George Floyd and many other black Americans in police custody, have quickly morphed over the last few days here in LA.

National Guard outside Self Edge LA.

The indiscriminate beatings, shootings, and arrests by the LAPD have again revealed the inherent racism in our policing system to a privileged audience that had been sheltered from experiencing it. Pleas for justice for George Floyd have also become pleas for LA’s district attorney to prosecute 601 deaths in police custody under her watch, as well as significantly defunding the LAPD’s budget.

The same streets that were filled with brawling, racist servicemen 77 years ago are now full of aggressive riot police and National Guard repressing voices for reform. Will it be the same in another 77?