Despite misleading statistics placing the pandemic unemployment rate (circa April 2020) at around 14.7%, Forbes places the number closer to 27.6%. This number, which is found by using a rate called U6, takes a more expansive look at the American work-force, substantially raising the number of struggling people in the country and drawing comparisons to another challenging time in our history.

The United States has only seen these levels of unemployment once before, during the Great Depression. And even in the depths of that devastating economic crisis, unemployment maxed out at 24.9%. Unlike the ineffective hemming and hawing in a contemporary Republican-controlled Senate, the Depression-era FDR administration rolled out innovative social programs to get Americans back to work and save average citizens from the predation of big businesses.

While not all of the measures imposed during the Great Depression still exist, some like the federal minimum wage and Social Security are still mainstays of our social safety net. One now-defunct program, the Civilian Conservation Corps, was one of the most experimental and well-regarded that made an indisputably positive impact on the nation and which helped unemployed people get back on their feet. Though there are many lessons to be applied from the New Deal initiatives of the 1930s, the CCC is one of the more impressive projects in American history and its heritage lives on not only in its ethos but in its clothing as well.

The Great Depression and the New Deal

President Herbert Hoover. Image via WHYY

The first of only two businessman presidents, Herbert Hoover was elected to office in 1929, the very year of the stock market crash. A staunch, profit-driven Republican, his deep mistrust of federal regulation not only allowed for the stock market crash, it marred his ability to bring relief to the American people. Like the second businessman president, Hoover’s conservatism led him to thoroughly bungle the crisis.

Refusing to create a unilateral federal approach to helping the millions of unemployed people in the country, Hoover instead sought support and relief from business leaders. He started an international trade war, which hurt average Americans and consistently refused to help the unemployed. Hoover, a shy man who avoided public speaking, seemed absent in the face of the crisis. Meanwhile, Governor Franklin Roosevelt of New York launched the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration to save the unemployed residents of his state.

“Hoovervilles” sprang up across the country, shantytowns bearing the name of the incompetent Republican president, unwilling to help the disadvantaged. When the new election came in 1932, Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a landslide.

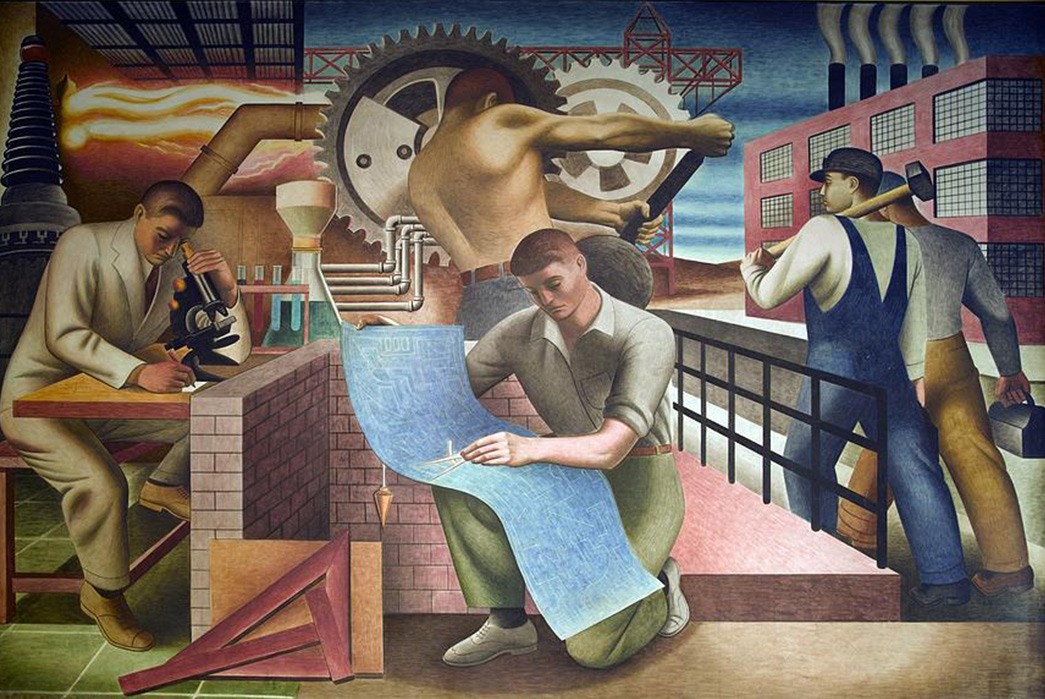

WPA Mural. Image via Fine Art America.

Unlike the Republicans of his day (and ours), FDR knew that federal intervention had the potential to lead to great things. They might not have been in the best interest of millionaires, but his far-reaching social programs brought tangible relief to the millions of Americans who were suffering and out of work.

Though intervening politicians have sought to devalue and despoil his two most famous contributions to the American people (minimum wage and Social Security), in the depths of the crisis and with the people at his back, FDR pushed for wide-reaching federal reforms that saved countless Americans on the brink of destitution.

Civilian Conservation Corps

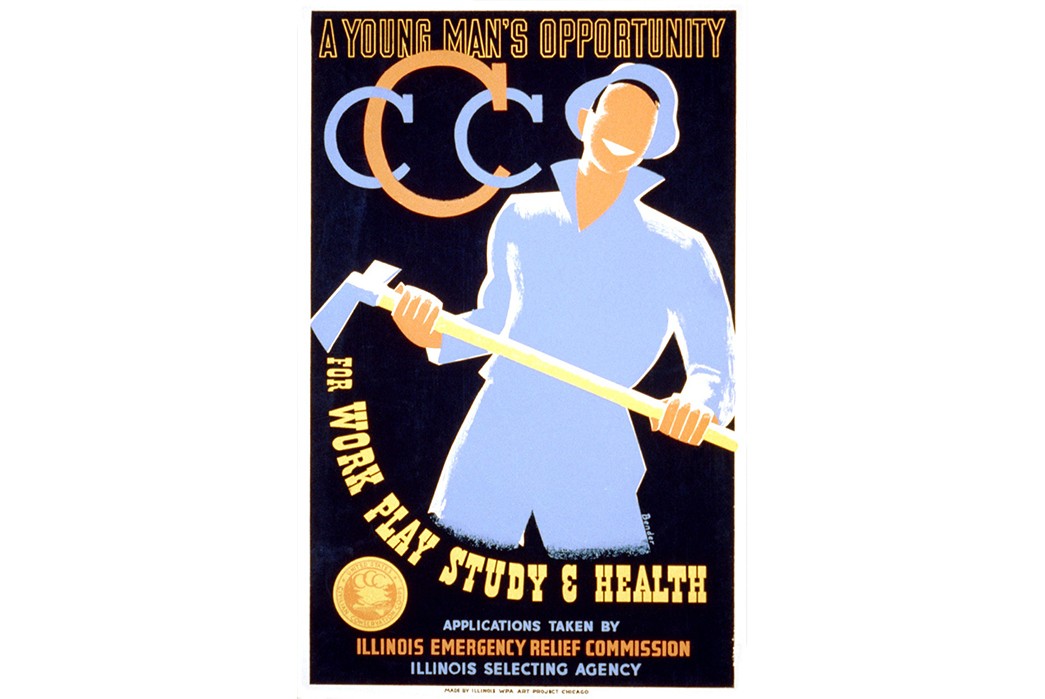

CCC Poster. Image via Library of Congress.

No good comes of having millions of young people out of work, poor, and frustrated. Across the Atlantic, 30% of the German workforce was unemployed as the country attempted to recover from World War I. The frustrated, idle German masses were especially susceptible to propaganda and hate speech, allowing for the rise of Nazism and the fall of the Weimar Republic.

In order to get people working and paid, President Roosevelt’s administration spent $3 billion over the course of nine years to fund the Civilian Conservation Corps. (This is roughly equivalent to $6 billion a year in today’s dollars.) The program began in 1933 and was open to men ages 18-25 and paid $30 a week ($590 today), $25 of which had to be sent home to support their families.

While another famous New Deal organization, the Work Projects Administration (WPA) put men to work on infrastructure projects like schools, post offices, and even painting murals, the men of the CCC were tasked with soil, forest, and parks conservation on an unprecedented scale. The ranks of the CCC were aptly called Roosevelt’s “Tree Army.”

CCC enlistees. Image via JSTOR.

In 1935, there were over 2,000 CCC camps spread across the country, often in wild, remote areas. Though the work was hard, over 3 million men were drawn to the program for at least one six-month term.

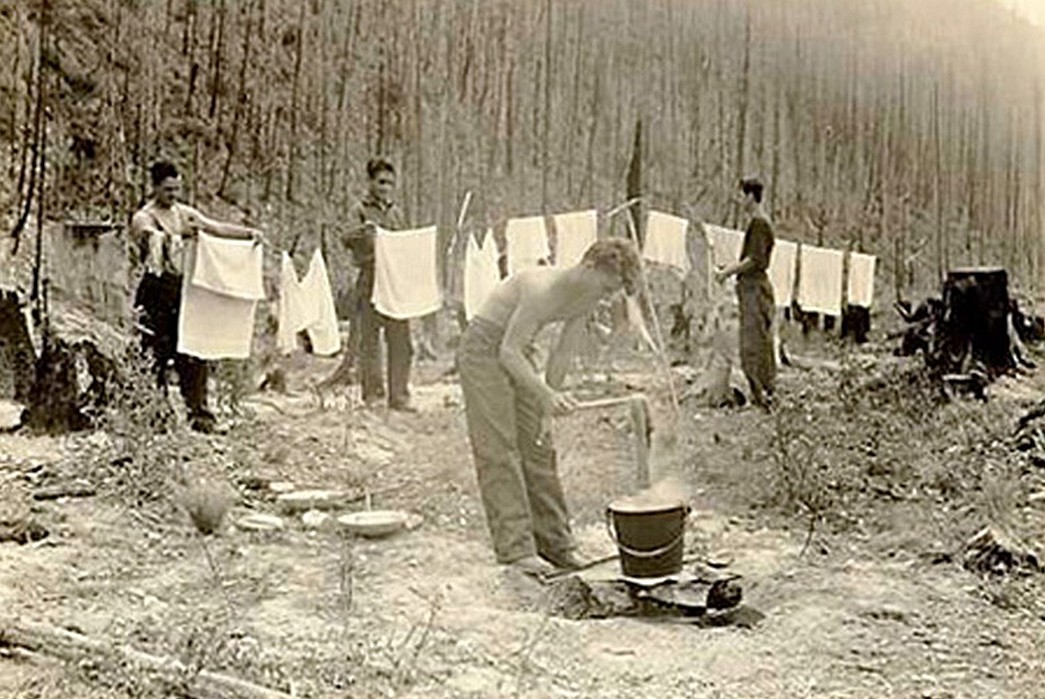

CCC members doing laundry in Glacier National Park. Image via NPS.

Though the U.S. Army had a role in maintaining order in the camps, the CCC was supervised by a number of technical agencies, the three most prominent being the US Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the Soil Conservation Service. The Forest Service was often seen as the most rugged and idyllic, with its work deep in the woods, clearing trails and planting trees, but there were many ways one could contribute to the conservation effort.

Things like surveying parkland, fighting wildfires, and building tourist facilities in National Parks (even establishing entirely new National Parks) all required specialized skills, often ones that young men didn’t have before entering the service. In these cases, LEM (local experience men) were brought on to act as foremen on these specialized projects, as well as pass on useful skills to the CCC boys. CCC alumni were more employable with these skills and could go on to support their families and themselves with the useful skills they gained in the CCC camps. Including many skills unrelated to the work they were doing in the nation’s forests.

CCC letter writing class. Image via DPLA.

Higher-ups in the “Tree Army” began noticing that thousands of their new enlistees could neither read nor write. Over the course of their tenure in the CCC, as many as 57,000 men learned to read for the first time.

Many camps appointed education advisers, who taught classes on everything from reading and writing to auto mechanics. Education was never a tentpole of the program, but many enlistees were able to get their high school diploma and some went on to college degrees.

The CCC Uniform

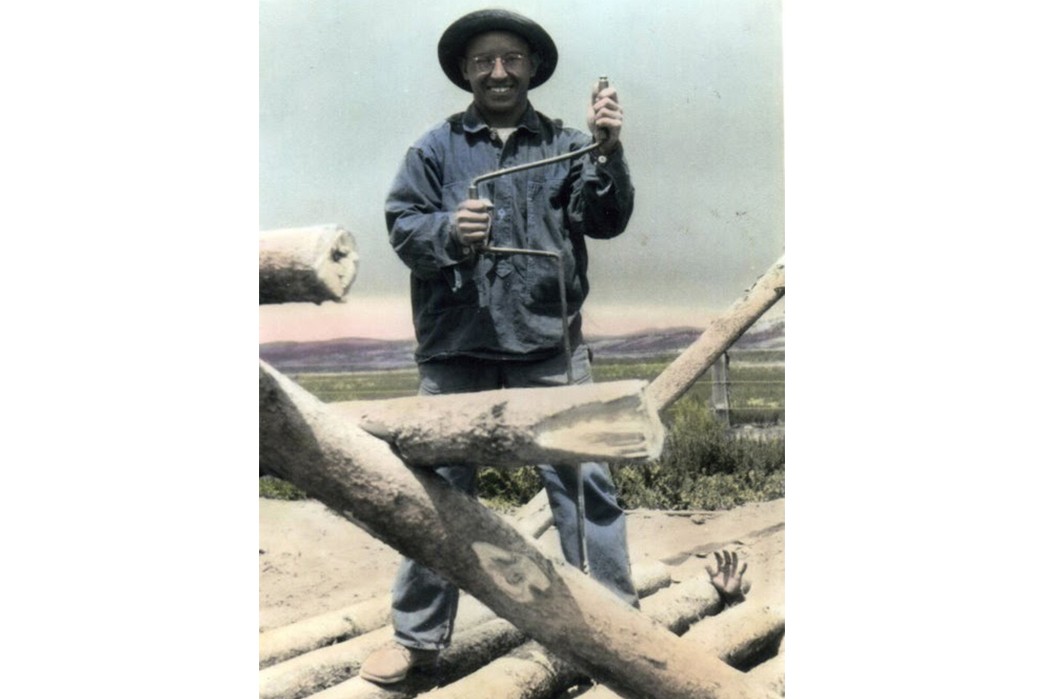

CCC men wearing the 6-124A work trouser. Image via CCC uniforms.

Every enlistee in the Civilian Conservation Corps was issued two uniforms: denim fatigues for work and woolen dress uniforms for everything else. Both uniforms were revamped around 1939-1940 as the U.S. government prepared to enter World War II, though many of the uniform pieces seen here would be repurposed for military use during that conflict as well.

With no need for camouflage, the CCC’s fatigue uniforms consisted of blue denim trousers and jacket. These outfits can be interchangeably referred to by their precise designations or as M-1937 fatigues (the Army changed their designation method in that year). The trousers had been developed in 1908 for the Coastal Artillery Corps and had been slightly tweaked for the Tree Army’s use, designated 6-124A.

Made with large patch pockets on the front and back and with a back buckle, these uniform pieces were occasionally worn well into WWII by various branches of the armed forces.

Image via CCC uniforms.

In 1939, the trouser design was tweaked into what was essentially a denim chino with patch pockets on the rear. The so-called 6-124B rarely if ever appears in the photographic record and was likely redistributed to some other entity when the U.S. entered World War II.

CCC man in jumper and trousers. Image via CCC uniforms.

The denim trousers were paired with a widely unpopular denim pullover, called the 6-125A. The pullover had its origins in the army’s very first piece of denim equipment, a brown overshirt that earned its stripes in World War I. Enlistees hated the pullover design and pleaded for a new design. Many pullovers from the era have been split down the middle to act as a jacket, which the CCC eventually go, but not til 1940, when the CCC received a more conventional denim chore coat.

Pullover torn in half with one chest pocket removed. Image via CCC uniform.

The woolen dress uniforms had infinitely more variations, but typically consisted of a buttoned shirt, tie, and slacks. These uniforms saw the most marked changes as the Quartermaster Corps totally re-designed the Armed Forces’ uniforms from their more antiquated WWI-era styles.

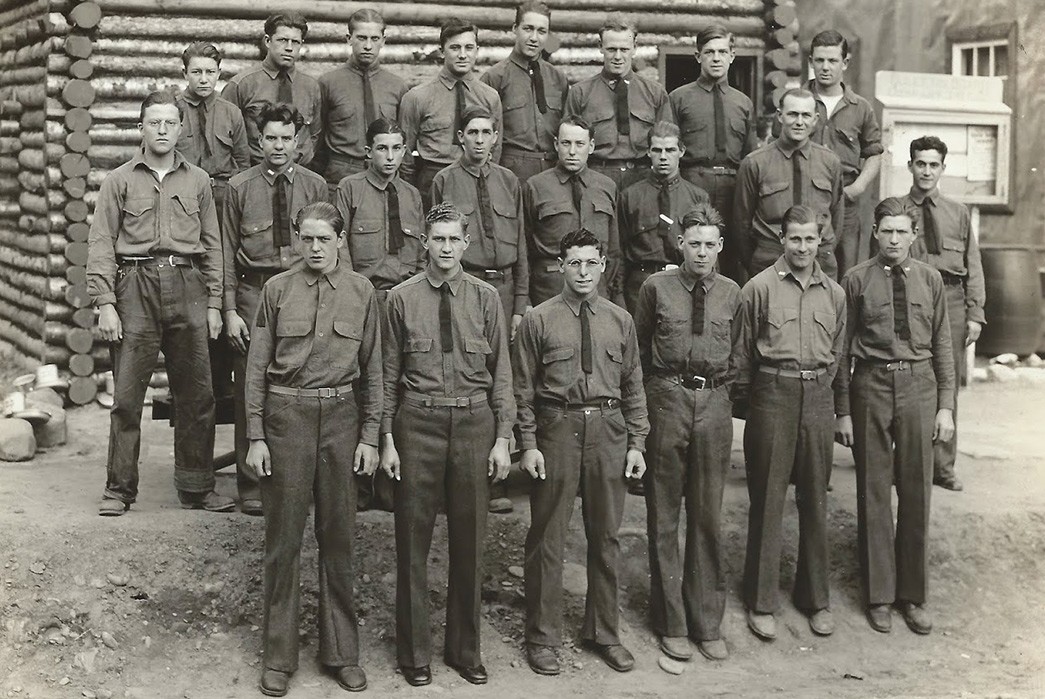

Mix of dress uniforms. Image via CCC Uniforms.

The above CCC members wear a melange of shirts, some old and some new, but across the board, they’re wearing WWI woolen trousers, which would eventually be scrapped in 1937 in favor of the higher-rise, wide-leg chinos many associate with WWII army uniforms. Much like the denim fatigue shirts, CCC enlistees were first issued pullover shirts, which eventually became regular button-downs with a combination of enlistees’ complaints and an influx of rearmament funding in the late 1930s.

CCC men in late 1930s dress uniform. Image via DPLA.

Despite the distinction between dress and fatigue uniforms, enlistees often mixed and matched their denim and woolen pieces, especially when the temperatures fell. Many periods of uniform styles intermingled as well; it’s not uncommon to see WWI-era breeches along side more modern WWII chinos.

The 1939 CCC uniform. Image via CCC Uniform.

The above publicity shoot showcases the 1939 winter uniform. Unveiled in an appropriately woodsy shade of spruce green, this uniform was allegedly designed at the behest of President Roosevelt himself, who felt the state of the CCC’s uniforms were rather poor. The Department of the Navy designed the spruce green suit and camps began receiving them by 1940.

Due to their introduction late in the life of the CCC, these jackets are some of the hardest uniform pieces to find. Essentially a civilian suit, they never got an official designation from the Quartermaster Corps. With the woodsy CCC logo (heretofore not included on uniforms) and the deep shade of green, the new uniform remain most closely tied to the works of the tree army in the popular imagination.

The CCC’s Legacy

Civilian-Conservation-Corps-Core-The-1939-CCC-uniform.-Image-via-CCC-Uniform.

The Corps disbanded in 1942, but their accomplishments would endure. Nearly 3 billion trees had been planted by Roosevelt’s Tree Army, vastly improving the health of the country’s near-decimated forestland. The corps fought wildfires, halted soil erosion, and improved drainage across huge swathes of territory.

Thousands upon thousands of young men were able to contribute not only to the health of the nation, but to the finances of families back home—although many CCC men never returned to their hometowns. Many enlistees in the program traveled great distances to take part in the conservation effort and eventually settled down in the small towns near their camps. The program enjoyed near universal support for the majority of its existence, ultimately forced to close in order to better aid the war effort abroad.

Civil service, especially one devoted to the betterment of the nation’s natural resources seems like an ever more important project. With climate change and rising waters eating away at our country’s lands, a modern equivalent of the Corps could be an excellent thing. Especially now, with a fractured political environment and mass unemployment, it could do us good to send our young people across the country, working together to help them be financially stable and to save the wide open spaces that are so integral to the American experience.