White Oak Economy is a monthly column by denim journalist veteran, Amy Leverton where she examines the interplay between the worlds of high end artisanal denim and the mall brands behind them.

I recently moved to America from England, and I have to say that being a Brit in the US has done me nothing but favors. Nobody loves a British accent more than the Americans; they think it’s both cute and intelligent (bonus), I’m welcomed, pandered to and made allowances for countless times a week and I bloody love it… until recently that is.

Unfortunately, since last month’s infamous Brexit situation, us Brits are now also associated with bigoted, narrow-minded racism: yay! I mean, I am exaggerating a little, but the English certainly don’t have the flawless sheen we once had, that’s for sure.

It was strange and scary witnessing the referendum from across the pond, but I have to say I was glad to be over here and not over there when it happened. And I am also pretty glad I’m over here, not over there right now, because the uncertainty, the atmosphere, and the social tension have so far continued.

Photographer Nick Knight wrote on his Instagram the day after the result: “Xenophobia, ignorance, stupidity and fear are now the forces driving this country.” He’s not alone in these thoughts of course but many remain staunch in their decision to leave, and the country is still divided. It’s a tough time for ‘Great’ Britain.

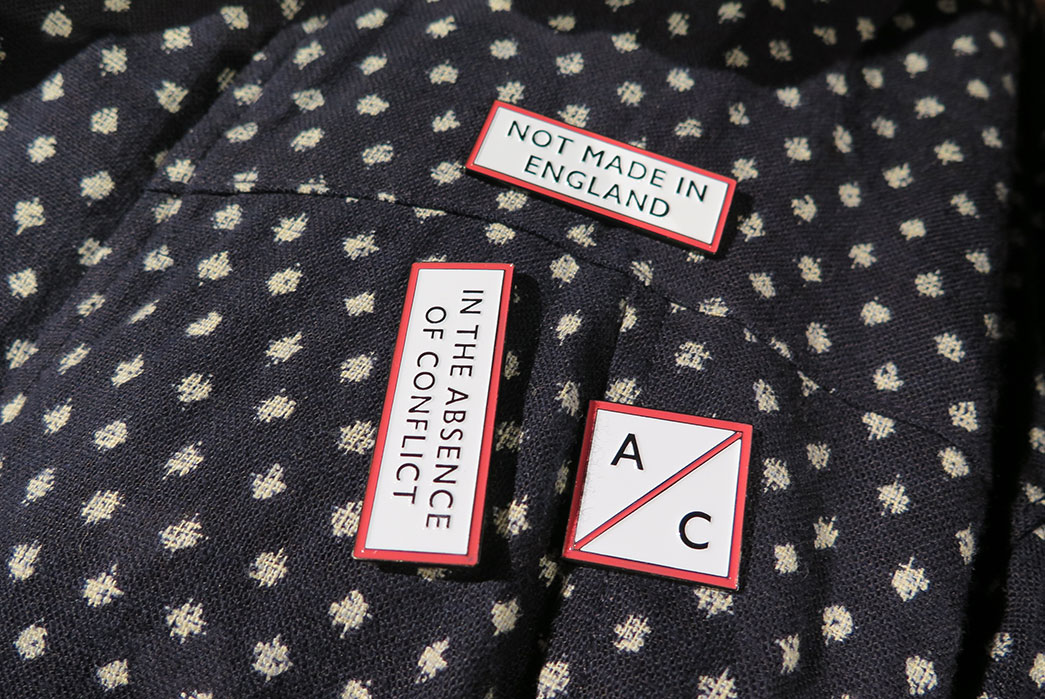

It’s also very interesting to be talking about this subject now because we’re in the middle of a very exciting movement of Made in the UK denim brands. I’m sure you’ll have heard of a few of them: there’s Endrime, Dawson, Burds, I and Me, Blackhorse Lane, Story, Bethnals, Waven, King & Tuckfield, and the longer-standing Hiut and Tender with, of course, many more besides. Not all of them manufacture in Britain, and as it stands England has no existing denim mill so we can never boast the same as a 100% Made in America tag, but there is certainly a new generation of denimheads carving out a beautiful scene in London and the surrounding townships.

Mohsin Sajid sews at Blackhorse Lane. Image via Sadia Rafique.

Until recently, I was a part of that crew, and it was so heart-warming to witness the sense of community these guys created for themselves: sharing machines, fabrics, distribution tips, drinks, and emotional support. This burgeoning denim scene was already on my list of subjects to cover in my Heddels series but then BOOM; the plot just got a twist!

At this stage, nobody knows what the future holds for Little Britain post-E.U.; it’s too early to tell, and article 50 has yet to be implemented. But I spoke to a bunch of my buddies to find out initial concerns and thoughts, while at the same time delving deeper into this inspiring movement of individuals and their hopes for the future. I’m hoping my story will be a positive one, a ‘triumph over adversity’ tale, but let’s see, shall we?

First off I want to talk about nationality and nationalism because sadly, this is what the referendum ended representing.

Although I do have some lovely Caucasian friends, living in England’s capital means that we really are a diverse set of people. The melting pot that is London means that my buddies are Spanish, French, Pakistani, Italian, Swedish, Danish, German, Dutch, Bangladeshi, Turkish, Japanese, Australian, and many more besides. I’m not going to go into the obvious crap my nationalist British residents decided to lumber us with, I think it goes without saying that every single one of my friends bring nothing but positivity to the UK and anyone who believes we’re being swamped by ‘unwanted immigrants’ can bugger off as far as I’m concerned. London voted to stay in the EU because London lives with the reality of a multi-cultural society and knows it’s a positive thing. Little England voted to leave because they have no direct experience and were being total prats, basically. Sorry, but that’s my opinion!

Han Ates of Blackhorse Lane.

When it comes to the issue of immigration, I suspect that Blackhorse Lane Atelier is the best example of cultural integration in the UK denim scene. Set up by Toby Clark and Han Ates last year, the project sets itself apart from the rest, as it’s not only a local brand but also a manufacturer. The concept behind Blackhorse Lane is to reinvigorate Britain’s failing manufacturing industry and promote locally made products through their Atelier and factory in north London. Han talked to me about his dreams for the Blackhorse Lane set-up as “nurturing a multi-cultural community, where people work, live and eat together and are not perceived as immigrants or foreigners, but as inclusive and respected members of the community they have chosen to reside in”. They also know only too well that the very concept of Made in England relies upon a team of diverse workers. As Han explains,

“Our Factory Atelier is proudly multi-cultural, and our employees mainly consist of European migrants. We are based in Walthamstow, North London, and employ people locally to promote the importance of local manufacture in the British economy. If we did not have these multi-cultural migrant machinists living within our community, we would most likely not have a British factory; there would be no British brand, no British product, and no British media story to celebrate.”

But how do you feel about that concept, readers? I know I feel perfectly fine about it, but I wondered what the denim connoisseur consumer thinks when he or she buys a jean? You care about where it’s made that I consider pretty clear (and commendable), but I don’t hear much talk go on about the intricacies of what happens inside a factory. And that’s where I think there still needs to be discussion and education, something I hope to bring up on here again soon. Han explains that “It is common (especially in the major cities such as London, Manchester, Birmingham, Leicester) for many machinists to be first, second, or third generation migrants whose families have chosen to move to Britain from Europe or further afield to make our country their home.”

Some of the workers at Blackhorse Lane.

This is a story I hear all over the world and I’ve even heard it emerging in places like China, as the younger generations start to enter the workforce. At the end of the day, very few kids aspire to become a seamstress or pattern cutter at a factory and willing workers are dwindling. Han continues:

“The garment-making industry has traditionally not paid high levels of income for this type of work. While British garment factories have closed down, more recent generations of British workers have chosen to move away from the industry and work in the service sector or large supermarkets where the hourly rate is higher. The migrants are often more skilled and experienced with this type of garment making work and therefore more willing to progress it as a career in the UK.”

The fact of the matter is, Toby and Han’s operation is impressive, inclusive, and full of local migrants, so what on earth would happen if a) they weren’t here or b) they were sent back? As we covered earlier, there would be no ‘Made in England’ to celebrate.

Like the system or not, if you want to continue to purchase jeans (and unless they are bought directly off Roy and have his signature in them) then you have to accept that even small production-line factories would be nonexistent without some amount of foreign workers. Like I said, I see absolutely no problems with this set-up, but please do reflect on that, and we’ll discuss it in a further article. For now, let’s get back to Brexit.

Scott Ogden and Kelly Dawson of Dawson Denim.

Another side effect of the referendum result is through the financial burdens on home-grown brands through rising costs and a weakening Pound. Kelly and Scott of Dawson Denim mentioned that the cost of importing fabric from overseas has gone up significantly, meaning running their business got much more expensive literally overnight. Mohsin from Endrime has experienced the same and David from Hiut explained further: “For us at Hiut, we source our premium denims from Japan, Turkey, America and Italy. We have already seen prices go up by 10%. Our biggest market is here in the UK, so it has made us made us less viable as a business unless we can pass that cost on to our customers.”

Jess from I and Me is feeling it too:

“I manufacture my denim in Turkey, but I am in talks to produce my second season’s knit styles in Italy. The unpredictable economic climate will inevitably have a negative effect on my profit margins. Paying for fabric and Cut, Make, and Trim costs in euros is not going to be as straightforward, that’s for sure.”

And this is having a knock-on effect with retail too. Rudy from Son of a Stag chatted to me last week about how their store is feeling the pinch:

“Three months ago, Japanese yen was 195 yen to the pound; now it’s about 134 Japanese yen to the pound, and therefore we’ve spent a lot more on buying in the product. We’re making a big loss but decided to keep our prices low. We do distribution too and a lot of stores are paying really slowly already. Next year sadly I think we will see some changes and gaps emerge in the retail landscape.”

David Hieatt of Hiut Denim.

So, sadly it seems like the pro-leave camp have inadvertently put home-grown retailers, brands, and worker’s livelihoods at risk, and the uncertainty is palpable. But is there a positive side? Actually, yes!

Kelly from Dawson is always one to look on the bright side: “With the value of the pound dropping, it could potentially mean we sell more abroad. We’ve noticed that UK denim retail has dropped off for us, and this could be for many reasons (time of year, Brexit). However, our sales in Japan have dramatically risen.” So the yen-related problems Rudy mentioned above of course make UK brands even more appealing to Japanese buyers with their ever-strengthening yen.

Han has a similar optimism when it comes to Japanese buyers: “Countries such as Japan have been investing billions of pounds into higher priced, authentic British goods for more than 30 years. It is the strength of the Japanese economy and their long term support as consumers of our British products that has been the key fundamental reason why British brands, British factories, and British designers have been able to survive and create sustainable international businesses.”

I recently visited the UK and felt a distinct buzz in London, as well as a more comfortable financial experience for myself now I was a dollar-earner. And of course, tourism has immediately had an impact on the city. Opodo reported an increase of 42% travel from the EU to Britain in the four weeks after the referendum and Airbnb a 24% increase in bookings. Tourists are coming from Europe, Asia, the Middle East and America in search of a bargain, and if UK retailers and brands can benefit, maybe this will add a counter-balance to the other expenses? Maybe so, maybe not, only time will tell.

We will have to wait and see how the new immigration laws will effect what were the beginnings of a revival in British manufacturing. We will have to wait and see if the increase in import duties has a knock-on effect on brand’s prices and if that can be countered by the fallen pound. We will have to wait and see if retailers and customers will continue to invest in these home-grown brands and their elevated costs.

Promotional material for Hiut Denim, still made in the UK.

Just the other day, I read a piece about uncertainty in fashion; how terrorist attacks, political turmoil, the refugee crisis, and economic fluctuations are leading to an ongoing anxiety in the apparel business. David from Hiut hits the nail on the head: “The economy relies on confidence more than we would like. One day the pound is worth this much, one day it is worth this much; the difference is just confidence.” And confidence we are lacking. Brexit has taken the wind out of our sales, it has left people wondering, debating, and more than anything, holding out and doing nothing. We wait and see because we simply don’t know what the future holds for UK brands and UK economy.

I have to say it looks bad but then when I look to the group of talented and driven group of individuals behind the UK denim scene I have to say I remain confident. When speaking to each one of the brands, their final thought was unanimously upbeat. Jess from I and Me speaks of the community:

“Shared experience and information are key for small UK run businesses, particularly in the denim world. I hope we can all stick together to get the best out of the result.”

And Mohsin from Endrime adds the interesting slant that, “having fewer options will just make for some more creative thinking – as less is more, so to speak.”

But my favorite opinion came from David of Hiut:

“On the plus side, we believe in ideas, we believe in innovation, and, if there is ever a time to have some great ideas, it is now. The other plus side is when politicians are so monumentally crap; music gets better. It’s time for some punk.”