Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

Reading is truly fundamental here at Surface HQ. I greatly admire those who have put in the time to research or create something, then put it onto page for others to digest and reflect on. It’s kind of a tradition for media outlets to run down a list of essential summer reading, so I want to take the opportunity to celebrate some of my favorites that might appeal to readers of this column, and site. The astute regular reader might notice some themes echoed in some of my previous pieces.

Is it a clip show? Is it a listicle? Or just a good old beach reading list? I humbly present to you, the first ever Beneath the Surface Reading Round-Up.

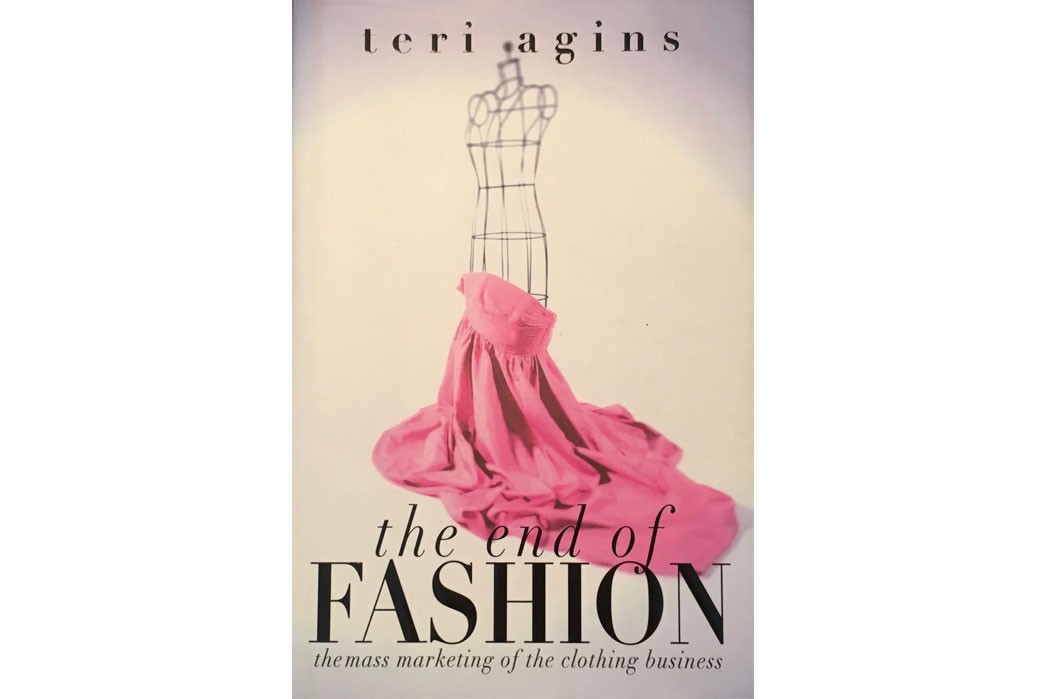

The End of Fashion: The Mass Marketing of the Clothing Business

By Teri Agins, published by William Morrow, 1999 Available for $8.69 at Amazon

It always bears repeating that the way things are now are not the way they’ve always been, so I love a good fashion book that gives context on what’s going on now while linking it to an historical past. Teri Agins is a veteran fashion writer who’s covered the business for more than 25 years for the Wall Street Journal. She’s in the enviable position of having a front-seat perspective on how the business of the industry has changed, writing for a publication not dependent on fashion advertising. This allows her an independence to do candid, in-depth reporting, and she doesn’t hold back here.

In this book, Agins draws upon 140 personal interviews to illustrate fashion’s transformation. Specifically: how an industry once dictated by European fashion houses through the decrees of their loyal fashion editors, evolved to large brands advertising directly to the consumer. These brands were driven by the needs of working women and men and ultimately learned to incorporate fashion from the streets. And in a parallel development, how fashion brands such as Ralph Lauren and Armani used marketing in different ways to achieve commercial dominance.

One of the book’s most engrossing chapters includes a detailed account about how Ralph Lauren tapped into the aspirational appeal of preppy clothing to build his empire – an appeal so seductive that his $8 an hour retail associates would obsess about $600 moccasins. And equally fascinating is the story of how Tommy Hilfiger turned his Lauren copycat brand into a genuine player by embracing how the street appropriated his gear.

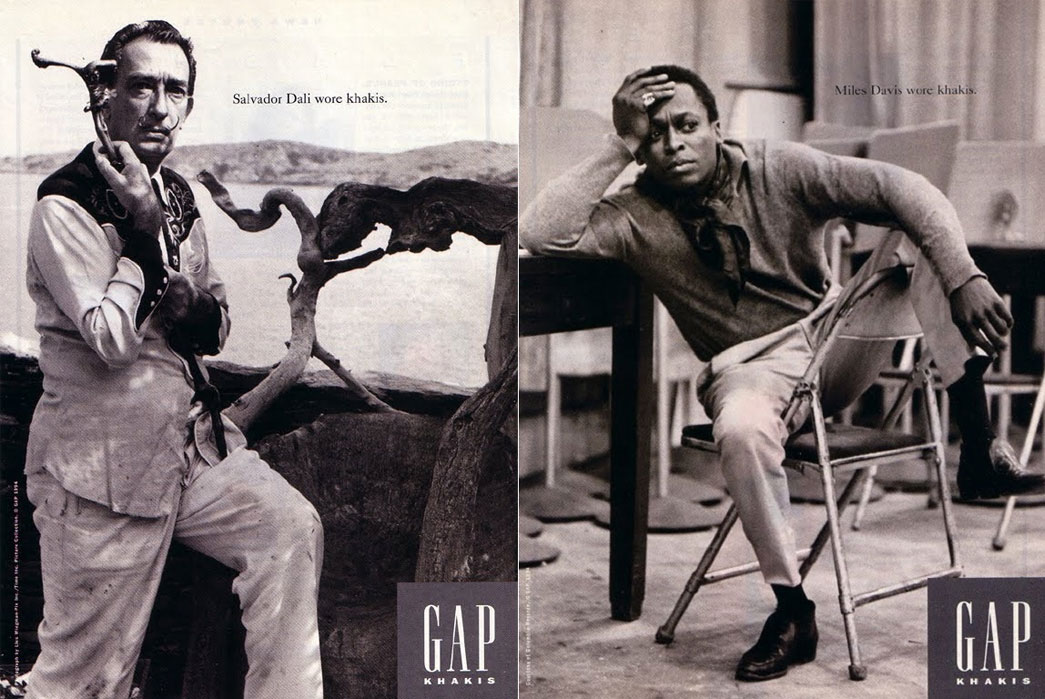

Indeed, marketing is the persistent thread throughout this book. It reminded me of Gap’s late Eighties / early Nineties advertising campaigns. Gap started as a boutique in San Francisco (called “The Gap,” as in, generation gap), selling Levi’s jeans and records. They later achieved great success as the source of staple goods like colored pocket t-shirts, jeans, khakis and sweatshirts (in that way, they were Uniqlo‘s obvious predecessor). With their legendary “Individuals of Style” advertising campaign and then the later, “Who Wore Khakis” campaign, they defined staple products as timeless – a blank canvas that expresses the individuality of its wearer. They remind me of those Apple TV ads that showcase all the creative things you can do with their technology.

The book reaches its logical conclusion with Blaine Trump bragging about her $10 K-mart shorts, heralding the subsequent emergence of fast fashion. But that’s a story for another time…

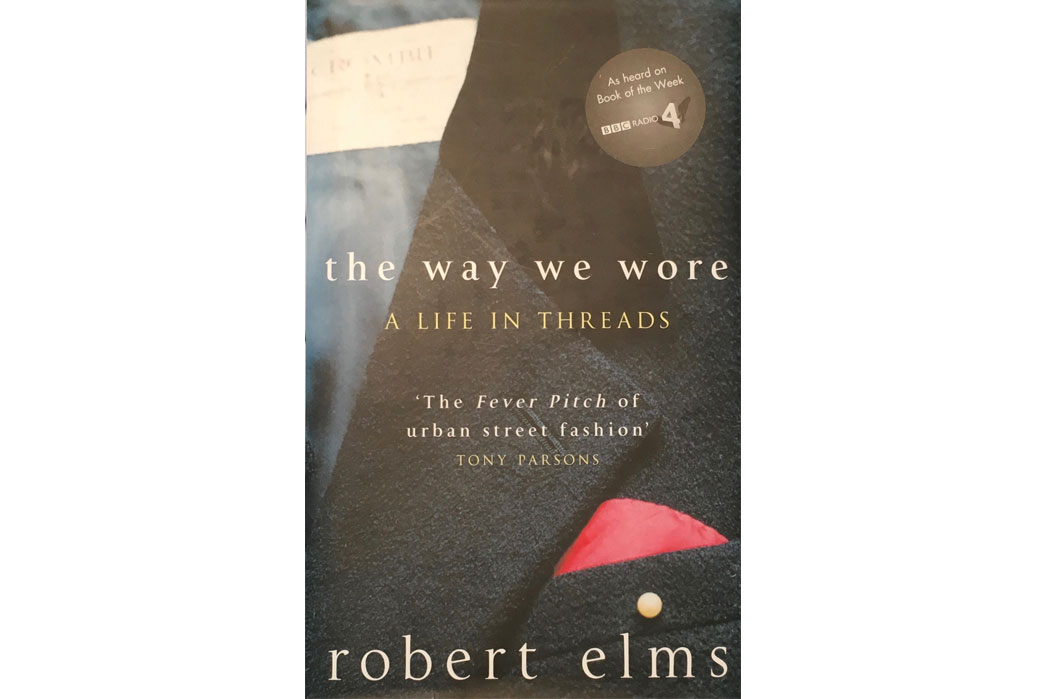

The Way We Wore: A Life In Threads

By Robert Elms, originally published by Picador in the UK, 2005 Available for $15.99 at Amazon

Is this an oral history of English street fashion or a memoir of a working class lad who happened to hit puberty when Britain’s modern youth culture emerged in the Sixties from the shadow of World War II? It’s both, and the fact that they are inseparable is part of the point. Elms recounts, in microscopic details, the evolution of his twin obsessions – clothing and music (with a few side trips into English football and its own peculiar code of dress).

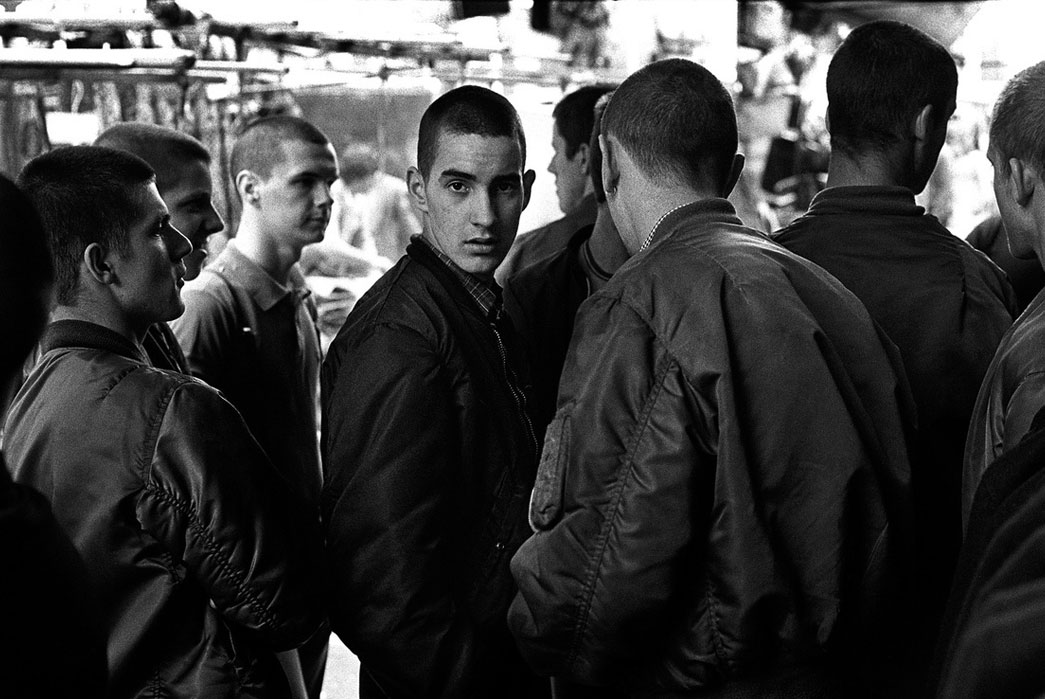

It was a time when fashion was still local and street fashion evolved quickly – spreading by word of mouth, hand to hand. He postulates that the original, oft-replicated post-mod skinhead look (off white Sta-Prest Levi’s – never worn with a belt but sometimes with a pair of suspenders; boots or brogues; Ben Sherman button-down shirt; topcoat by Crombie and Sons) was invented by a group of West Ham United Football Club supporters and spread to north London when Arsenal played them in the ’68-’69 season. As he tells it, Arsenal’s supporters took note of, ridiculed, then ultimately copied, the look – which then proceeded to spread through the rest of the country over the course of the season.

Fig. 2 – Skinheads in 1981, photographed by the great Derek Ridgers. Image via Vice I-D

The book is full of keenly observed details and anecdotes from a period where tribal doesn’t even begin to describe it. One favorite is how he rejected a ticket to David Bowie’s legendary last gig as Ziggy Stardust because Bowie wore platform shoes (a mod no-no, as per Rod Stewart, the singer who was one of that scene’s guiding lights). It’s a terrific example of the “us against them” attitude that tribes took towards one another – to define yourself by rejecting others’ values, as expressed through their appearance.

The most vivid portrait of this comes in the Seventies, when Elms adopted a southern “soul boy” look. At the time, there were two different soul scenes happening in England – one in the South that evolved with the times and one in the North of England that stuck to the Sixties classics (if you ever hear the term “northern soul,” this is what it refers to – as a warning, it quickly leads to a rabbit hole of obscure Detroit sides). He happened to travel to Sheffield United up north to see his London-based team (Queens Park Rangers) in his finest sophisticated southern gear – skinny, straight corduroy pants, pointy winklepicker shoes, a baby blue sweater – all topped off with a wedge haircut. He couldn’t have been more out of place in an area of the country where the look was defined by a wide legged, high-waisted, flared pants by a regional brand called Spencers. He clearly didn’t belong, and for that he got a half-brick in the ear from a local supporter.

Truth be told – I tried to browse through the book when preparing for this column, but it’s so vividly rendered and chock full of fascinating details I found myself re-reading it instead. A must read for anyone interested in exploring the ties between subculture and fashion.

Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike

By Phil Knight, published by Scribner, 2016, Available for $29 at Amazon

Fig. 3 – Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman (right) and the brand’s talismanic muse, Steve “Pre” Prefontaine (left). Image via Nike

If you’ve heard of Nike but aren’t sure who Phil Knight is, you’re surely not in the minority. It’s an iconic brand and most of you could probably name at least five models off the top of your head, but its origin is less known. These beginnings are the main subject of this book, which traces Knight’s childhood to the moment when Nike went public in 1980. It’s a good read and does a great job of evoking the Seventies in ways you don’t think of that often, and providing context for certain things we take for granted today.

Nike (and its predecessor, Blue Ribbon Sports) was founded by Knight and his University of Oregon running coach Bill Bowerman – a secondary father figure even more demanding and taciturn than Knight’s own. They started as an importer of the Japanese brand now known as Onitsuka Tiger and catered to runners. The running category is huge now, but neither casual athletics nor aerobic exercise was a thing back then and running was considered to be “something weirdos did.” Knight built his business by going straight to the customer, hauling pairs to track meets to sell to athletes eager for an advantage – spreading by word of mouth, foot to foot.

Back then, access to capital was really limited for a start-up business. There wasn’t a network of venture capitalists looking to invest in the next big thing, so Knight had to rely on his local bank’s business loans. He ran Nike as a growth company so invested every penny of revenue back into product. While he reliably doubled sales year upon year, he was always in danger of running into an unexpected expense that would push him into bankruptcy – to complicate things further, banks were risk averse and preferred to see money in the form of deposits rather than goods. It’s this ongoing highwire act that drives this narrative, as Knight and team bounced from one crisis to the next. The whole book builds to their IPO, which finally provided some much needed support for their growth model.

Because of the timeframe of the book, you won’t hear much about Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, Bo Jackson or any of the famous athletes now associated with the brand. But you will hear about Steve “Pre” Prefontaine, a legendary runner at the University of Oregon – it’s hard to imagine a runner being a rock star these days, but it might be helpful to remember that college athletics were as big as (if not bigger than) professional sports back in the Seventies. His style was to go all out in the beginning of a race and not relinquish – as such, he was a perfect embodiment of Nike. He died in a car crash before the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, and his first signature shoe (The Pre Montreal racer) is one of the many classic designs of the pre-Air Nike. It’s no coincidence that every groundbreaking technology that Nike came up with was first put to use in running shoes, still after all these years – the sport is still woven into the company’s DNA.

Fig. 4 – The Nike Pre Montreal (retro “vintage” edition) – via Vntg Sneaker.

Towards the end of this book, Phil Knight lets slip a tiny golden nugget – Nike issued their IPO the same week that Apple did. In fact, he valued his own company so much that he held steadfast in pricing his initial offering at the same price that they announced, against his financial advisors’ recommendations. It’s a perfect tidbit – my sense of Knight throughout the whole book is how similar his level of focus is to Steve Jobs. If you need to know one thing about his vision, it’s that Nike was always driven by what was best for the athletes that wore its shoes.

Oh yeah, and if you had invested the same amount of money with both Apple and Nike at their IPO offering price, your Nike shares would be worth more than double Apple’s. And, as much as Apple has transformed our interaction with technology, it’s possible Nike has had a similar impact on our daily interaction with sport and fitness.

Just saying.

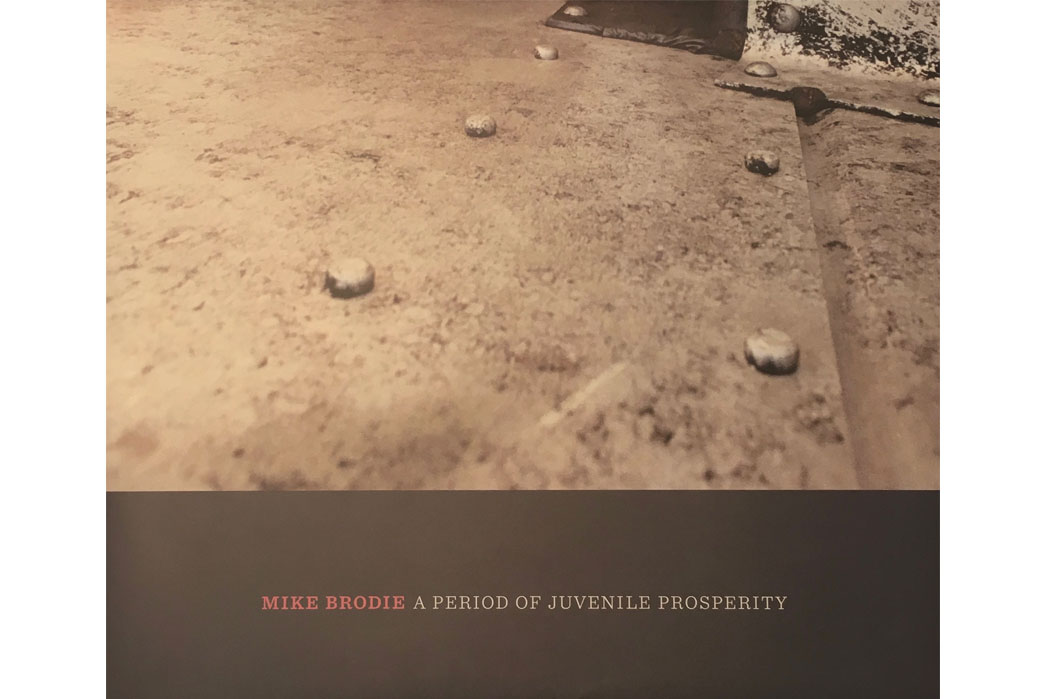

A Period of Juvenile Prosperity

By Mike Brodie, published by Twin Palms, 2013, Available from $75 at Twin Palms

I love photography and a good photo book – they’re not what I’d call beach friendly, but they can be a fantastic window into the human condition. Mike Brodie is a photographer who became famous through the Internet as the Polaroid Kidd from his photos taken on his rail and hitchhiking journeys living as an itinerant across the United States – a hobo’s life.

This book collects some of his later shots, after he switched to 35mm film, but before he retired to become a diesel mechanic in Oakland. There are a few that look downright heroic – a man dangling off the back of a moving train giving the finger to the viewer is one of its most notorious.

But it’s the other, less glamorous, photos that capture my attention, the ones that are brimming with humanity – I wish I could responsibly show them all here. A young man being tended to in a fever, another in a hospital with a brace around his neck. A man holding wild-foraged berries in his tattered hat, in what is clearly a treat for him and his companion. The ultimate bathtub soak, the water filthy with the grime of life lived sleeping on cardboard, on the rails and the back of a pick-up truck. And through this life forged by uncertainty, travel and literally surviving hand to mouth, some of the most powerful images are of those who have found peace in the moment. Because tomorrow is promised to no one.

Fig. 5 – Tub soak from A Period of Juvenile Prosperity. Image via Yossi Milo Gallery

What these books have emphasized to me is that each day is an opportunity to learn, experience, reflect – I hope you find them as rewarding as I have.