The word linen has been so generalized and coopted it’s often difficult to sort out what it actually means. Beyond what Elton John wants you to lay him down in sheets of, linen is a natural plant fiber that people have been using for thousands of years. You can find it in thread, shirts, sheets, embroidery and pretty much any other type of woven fabric.

Linen is often mistaken for other fibers and misconstrued as something itchy you only wear to summer weddings, but we’re here to brush away those misconceptions and educate you on the wide world of linen fibers.

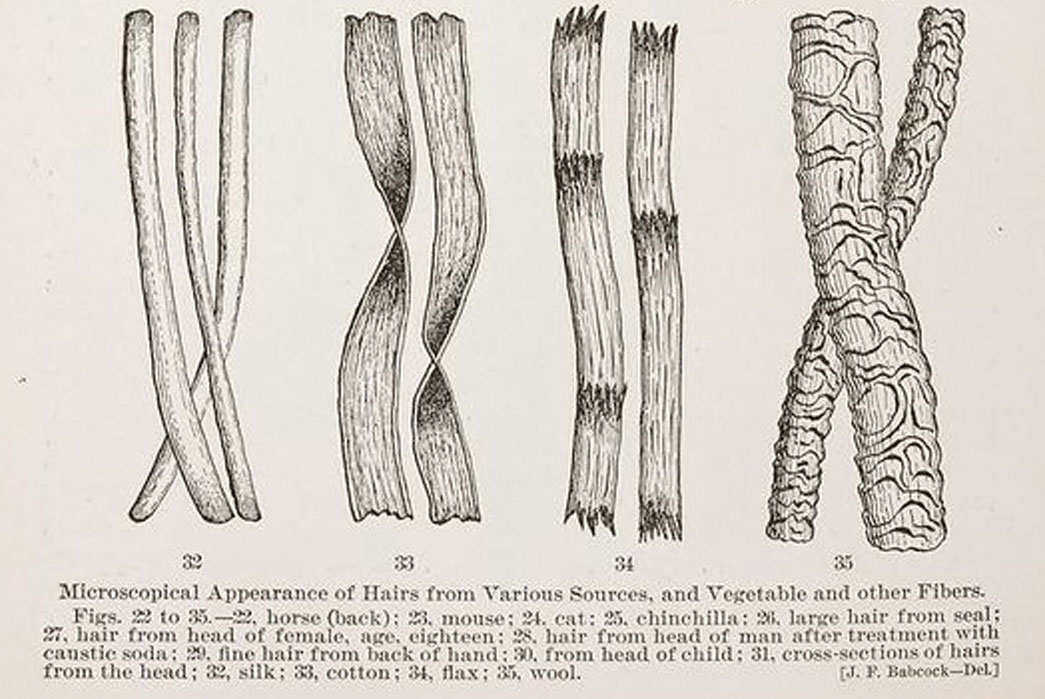

Various linen fibers. Image via Google.

Linen is a bast fiber, which means it comes from the inner part of the plant. In linen’s case, that’s the flax plant. The word linen comes from the Latin word for flax, linum. The linen fiber is not to be confused with bed linen, although the two are connected. Linen’s association with bedding and the origin of the word comes from the fiber’s close association with throws, bed sheets and ropes since ancient times.

Linen as a fiber looks very similar to hemp and the two can be hard to distinguish from each other without a microscope. The two share a lot of the same properties too, although hemp is known to be a little darker and have poorer elastic recovery than linen. Linen has a beautiful, natural color, varying from ivory to ecru, tan and grey.

General Properties of Linen

Microscopical appearance of various vegetable fibers. Image via Google

- World’s strongest natural fiber: linen is ~30% stronger than cotton, making linen fabrics hard wearing and durable for several decades

- Eco-friendly life cycle/recyclable and biodegradable

- Soft hand: linen is stiff and scratchy at first, but softens with wear and wash*

- Structurally sound fiber: linen garments keep their shape well

- Colourfast and launders well

- Naturally hypoallergenic

- Anti-static

- Good moisture absorbency: can absorb 20% of its weight (before it feels damp)**

- Highly breathable

- Low elasticity

- Long extraction time (from plant to fiber)

*Vintage linen is very desirable as the soft hand feel of vintage linen is hard to replicate

**This is less than both cotton and wool. However wool becomes weaker once wetted whereas linen gets stronger. Absorbency is also dependent on the particular weave of the fabric and cotton tends to hold onto moisture for longer than linen.

Linen fibers are much thicker than cotton and thus linen fabrics have a lower thread count (number of yarns per inch of fabric) than those of cotton. However, it should be noted that thread count does not necessarily correlate with good quality, especially not when comparing two different fibers. In spite of linen’s relatively low thread count, linen is considered far superior to cotton in both quality and eco-friendliness and is priced accordingly.

Antique linen sheet dating from the late 19th century. Made from fine linen and intricately embroidered with floral motifs and monogram. Image via Fleur d’Andeol.

Linen, unlike cotton, takes a long time to soften up. Linen sheets typically needs three years of use before they develop their natural sheen. Cotton, on the other hand, has a much softer hand when comparing freshly woven fabrics.

But good things come to those who wait, as linen sheets typically lasts for two to three decades whereas sheets of cotton sheets commonly only lasts between three to five years. The wrinkly nature often associated with linen is due to the fiber’s stiffness in the early stage. Once worn and washed many times, those wrinkles fade away. Ironically, lignan, a plant compound found in the flax plant is known to have anti-wrinkling properties on human skin!

Linen is, from ancient times, known to have healing properties, given the fiber’s high breathability, antibacterial, and hypoallergenic properties. Linen is anti-static which explains why it doesn’t cling to the body and generally stays clean longer as this naturally repels dirt. Linen is also a temperature-regulating natural insulator, like silk, which is due to the fibers permeability and hollow core. This helps the body to keep cool or warm depending on the seasons.

The anti-static and hypoallergenic nature of linen, means that it’s good on your skin, and so sleeping in linen should help you sleep better. Less so today, but linen has known to be a status symbol and given the fibers extensive range of functional benefits, it’s no surprise that linen is largely associated with luxury. Prestigious and expensive hotels will typically make use of linen bedding.

What’s the History of Linen?

Patterned ancient Egyptian linen. Image via NoBell.

The use of linen in thread and rope has been known to man for more than thirty thousand years which long predates the use of wool. By 3000 B.C., at latest, humans found a way of weaving the thread into textiles. The coarse fibers were spun into yarn and was used by Egyptians for sails whereas the finer, more expensive linen would be used for high-prized tunics and such. It’s claimed that Egyptians even used linen as currency.

One of the oldest woven garments known to man: a pleated linen shirt from the Egyptian Tarkhan dynasty, dating back to 3000 BC. Image via Petrie Musem of Egyptian Archaeology.

In North Africa, Egypt and Sudan it was common to wear linen whereas it was common to wear wool in West Asia, Greece, and Germany. In Roman times however it was common for Europeans to wear tunics made from linen, typically worn underneath their wool robes. This is why linen, in the Western part of the World, became associated with underwear (the word lingerie derives from the french word for linen: lingin) and the white color in underwear also comes from linen, which is naturally “light”. The Islamic Empire preferred linen (and cotton) over wool as well.

In Europe it’s been a tradition to pass down dresses, sheets and other types of linen cloth as a heirloom from generation to generation. This too denotes linen’s long lasting properties as well as the high quality associated with the fiber. Linen was the fabric of choice up until the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century when the cotton of North America won ahead due to the technology of new spinning machines that made cotton manufacturing more affordable.

How is Linen Grown?

Flax plants used for linen. Image via Osca Ironing.

Flax plants are one of few crops still grown in Western Europe with about 75,000 acres grown annually. The growing cycle of flax is short with only around hundred days from sowing in March to harvest in July. The plant has a lot of potential and is thus not mowed, but instead uprooted. This is because the flax plant has a wide range of use which extends the linen used in the textile and garment industry.

Producing linen is an eco-friendly process, meaning its life cycle has a small ecological footprint compared to cotton. This is due to several aspects such as the longevity of the linen fiber, and the low use of water, pesticides, and fertilizers in growing flax compared to other crops. Also, the bi-products – flax seeds, oil, straw, lower-quality fiber are used in producing a wide range of products: from lino, soap, healthy oil to paper and cattle feed. Flax seeds, for one, are very popular nowadays in both food and medicine. Normandy and Belgium are some of the best places to grow the flax plant due to the cool climate and temperatures.

How Does Linen Become a Textile?

Inside L.A Liniere in Bourbourg, France., a staff member checks the flax. Image via AFP.

Although the growing cycle of flax is short, turning the plant into linen fabrics is generally a time consuming process. The process naturally varies depending on the farmer or mill but most of the process is fairly well regimented. The first step, after harvest, typically involves stacking the flax in hedges to dry. This is done to ease the process of removing the seeds.

Next, the flax are retted, which is a sort of soaking process, done in order to soften the fibers. Traditionally, this was done in rivers, but for ecological reasons it’s now done in fields, typically the fields where the flax is grown. Retting is still commonly done with the help of Mother Nature, in a sort of natural decomposition: The fibers are left in the fields for several weeks and exposed to rain, dew and sunshine throughout. This is done to break down the pectin in the fibers of the flax plant. The flax are then typically rolled and stored for another three months to soften, but sometimes the retting process includes another drying process in between this. After this, it’s time to strip and comb the fibers.

In a similar fashion to other natural fibers, the flax fibers are separated from the straw and then graded according to the length of the fibers which indicates quality. The short fibers (tow) are used for the coarser yarn, which is typically made into hard wearing fabrics in garments and upholstery as well as thread (e.g. for sewing leather goods). The long fibers (line) are used for the finest linen yarn which is typically woven into bed linen, fancy throws and fine garments.

The spinning process is also similar to that of cotton and wool. The fibers are drawn out onto sinuous ribbons and then plied together to similar weights/thicknesses and spun onto cones. The line yarn is typically “wet spun” which means, amongst other more technically complicated nonsense, that the spinner incorporates heated water soaking the yarn ahead of rolling. This is done to swell the fine yarn in order to make the process possible. Wet spinning makes for a shiny, smooth appearance. The tow is typically “dry spun” for a more irregular and napped appearance. Before weaving or knitting the linen yarn into fabric, it’s examined thoroughly, and it’s typically quality tested once again after this.

As with other natural fibers, it’s common to bleach or dye linen. This can be done before the weaving or knitting process, called yarn dyeing, but it can also be done as a textile or garment dye. Dyeing linen requires great skill as it’s a delicate process not to ruin the structures of the fiber, when using necessary chemicals to remove any remaining non-fibrous residue or pectin first. Because of that it’s quite common to leave linen in it’s natural state of color, which goes hand in hand with the historical aspects of healing and eco-friendliness associated with linen.

What Brands are Using Linen?

Blluemade’s Indigo Linen Jacket (well, almost – 91% linen, 9% polyamide). Image via Blluemade.

Given linen’s rich history and long range of positive features, it’s easy to think of it as a forgotten fiber – especially when it comes to linen’s relatively small role in the contemporary garment industry. As previously mentioned, linen has a bad name for wrinkling easily as well as being tough to iron.

This might be true of newly bought garments, but the statement or accusation also follows a pattern of fast fashion business, where consumers are shopping with the unrealistic expectations that their clothes are at their full potential with first wear and that they retains this perfect state throughout its life. These ideas are largely orchestrated by massive corporate retailers, and I, for one, hope consumers will realize the fantastic benefits of wearing, caring for, fixing and keeping ones clothing for longer periods of time, thus extending the life of their clothes, plus reaping all the benefits of continuous wear, minimizing the scale of manufacturing at which we produce clothes in the twenty-first century.

A relatively new brand on the market that uses linen almost exclusively in their collections is Blluemade in New York. Blluemade’s linen is sourced exclusively from Belgium, and each product is sold with a reference number (approved by European quality control collective, Masters of Linen) as a guarantee that the linen used, is of the highest quality and of European origin. Furthermore, the linen meets the OEKO-TEX Standard 100, certifying that no harmful chemicals have been used in the process of making the linen. Blluemade furthermore utilize natural dyestuffs like indigo in their garments, thus minimizing their ecological footprint, plus providing a beautiful color that will fade like denim. You can find Bllumade’s products on their website.

Other brands that are known to use linen in their collections are Mister Freedom and Tender, that emerged with some beautiful, natural knitted and woven linen for their SS16 collection. Generally, replacing cotton with linen (or hemp for that matter) is a great initiative for the environment as linen tends to last longer and the manufacturing process has a smaller ecological footprint. It will typically cost you more upfront, but judging by the longevity of linen, it pays off in the long run.