When I discovered @postwarwesternwear on Instagram, Dr. Sonya Abrego’s online companion piece to her upcoming book, “Westernwear and the Postwar American Lifestyle,” I was ecstatic. There are many in our niche of fashion purporting to be experts, but unlike these armchair historians, Dr. Abrego has the education and experience to back herself up.

We sat down to discuss the historical Wild West that is fashion history, her experience in many of the country’s coolest clothing archives, and what we can look forward to in her upcoming book.

Dr. Sonya Abrego. Via sonyaabrego.com

Sonya Abrego: I’m Sonya Abrego, I mostly identify as a fashion historian. But my background is really design history, but I focus on clothes and that means bringing in a lot of cultural history and other things into play because fashion doesn’t exist on its own. And it’s like an interaction with everything else that’s going on.

Right now I’m working on a book about western wear. Post-war western wear specifically because you have to set limits on these things. This was coming out of my PhD dissertation, which I completed at the Bard graduate center in 2016. And it’s a long time in the making because these things take a long time.

So the project is based on archival research at four different companies: Lee, Wrangler, Pendleton, and Miller Stockman, who are a catalog and also did Western shirts. It’s taken me to those archives. I’ve also had a fellowship at the Autry museum and at the Cowboy Museum in Oklahoma. But as these things go, I was also working in teaching in between, that’s mostly textile history classes right now at Parsons and the graduate school at FIT.

Heddels (Albert Muzquiz): How did this come to be? How did you get to where you are now and your interests?

Outfit by Nathan Turk. Image via PBSsocal.

SA: It is not a straight line. My interests are a little bit all over the place. In terms of kind of narrowing the topic though, I’ve done a lot of work on post-war American culture, and I knew whatever I was doing was going to have some crossover between clothing, popular culture, advertising, film, and Western wear is all of that, the way it comes and as much as I love the designers like Nudie Cohn and Nathan Turk and Rodeo Ben and the really flashy rhinestones on bespoke suiting, which I love looking at, I’m more interested in how these styles blended in.

How did we get from something that was workwear in agricultural communities and the rural West and Southwest to being part of our every day? That’s what led me to brands that existed as workwear companies and in a moment when they were trying to transition more to ready-to-wear, when it moved to people who lived in the suburbs that maybe just wore jeans on the weekend.

H: So what’s the special thing about that post-war period? Is that just Westernwear really hits the mainstream?

SA: For the brands I’m looking at? Yeah, that’s when their confidence in their advertising is really taking it to national audiences more. We can see examples of Levi’s, as early as the 1930s, being featured in more mainstream publications advertising to their readership when they were still making just Union-Alls in the 19-teens, but post-war it’s different. Because manufacturing was so much more accelerated.

These companies were really big by that time, they had their own mills, and they were buying up other makers. It’s becoming a big business and so they want to reach more people and they start diversifying and they start diversifying how they’re marketing.

What are essentially the same clothes… now I’m not going to say that to, like real denim people that they are the same, because we all know there are so many differences, but in the world of fashion, they’re the same clothes, right? It’s like shirting and five pocket jeans. So that’s, that’s why I’m interested in it. The design doesn’t change that much, but the market changes and the world changes around it. And all of a sudden you start seeing this.

Bill Picket, a Black rodeo icon. Image via Denimdudes.co (Dr. Abrego’s article)

H: I read in your article on the Black cowboy, which I really enjoyed, about the commercialization of the rodeo. Is that something that’s going to feature into this book?

SA: Rodeo culture definitely is a big part of how these companies branded themselves and they had a history of promotions and connections to that. So whether that’s using cowboys actually on their flash tags and in their print ads, or if it’s just sponsors, banner, posters, that kind of thing. And, the forties and fifties, that post-war moment, was really considered the “Golden Age of Rodeo.” Meaning the, the business of rodeo became more professional.

And Gene Autry was a huge investor and sponsor as you start having rodeos as bigger public events with greater corporate sponsorship and not just the community state fair. But it doesn’t take away from like the contest and the riders and what they were doing. It was just making it a bigger and more widespread kind of entertainment.

View this post on Instagram

H: If there were someone reading this that wanted to pursue fashion history in this more academic way, how, how would they go about it? How did you go about it?

SA: I went about it in a weird way. I don’t know if I would follow me.

Also, fashion history… It’s just interesting as a discipline. If you talked to someone about something like Film Studies, maybe 30 years ago, they might think that’s weird, right? Like, why would you get a degree to write about a movie? Well, fashion studies has kind of been dealing with similar things in the last 10 years. But there are way more programs now than when I started.

So I was selling and dealing vintage clothes on my own for a while, and then making money through doing that. And I mean, Westernwear, as you probably noticed, is everywhere and nobody writes about it. So for anyone who wants to do this professionally, it’s also of trying to find your niche of something that you’re interested in or that you might have a unique take on.

I went to a school that gave me a really well-rounded background in design history overall and specialized in writing about clothes, but there are other programs that are more exclusively fashion studies focused at places like Parsons and FIT, which are also great. So yeah, I mean, doing that graduate level is good. That’s helpful. There’s kind of no way around it, but there are so many other ways to access the material.

Most of what I study, museum collections don’t hold it. So I wasn’t doing a lot fellowships at the Met, because they don’t care about jeans and cowboy shirts! So it’s also trying to find where you can source your original material and write about something that no one else has written about, of which there’s still plenty out there.

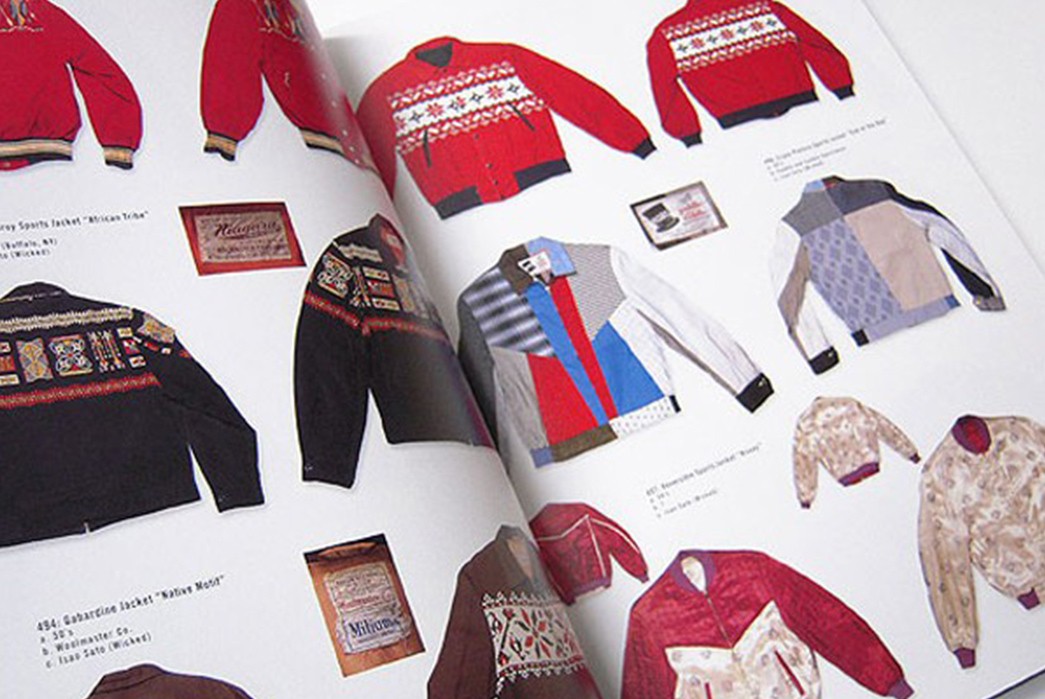

My Freedamn by Ron Tanaka. Image via Storm Fashion.

H: I feel like that’s the overwhelming thing about fashion history. It’s this “you can’t see the forest for the trees” thing where every Joe Schmoe is wearing jeans that they don’t care about. It’s hard for an average person to put themselves in the shoes of somebody, or in the jeans of somebody, in the fifties when wearing that was an act of rebellion or a more controversial stance. So does that feel frustrating when the Met doesn’t have a collection and you can’t follow these conventional routes of research?

SA: It can be, but I’m lucky because that’s where all my network of collectors and dealers comes in. I can call people and get a pair of [Levi’s] 701s to take photos of, right? And that’s great. And all those people tend to be really helpful because the passion is to get more knowledge out about this stuff and we appreciate the same sorts of things and help each other out. So that part of it is great.

In terms of being an academic and having a record of postdocs and fellowships, those are institutions that wouldn’t necessarily support what I do. So I wouldn’t even apply for a lot of them, you know? Or it’s a way of framing it too. Because I look at fashion but it’s essentially American studies and American history, that I’m contributing to also. So it’s also framing what you do and framing how you’re looking at it. And, as you mentioned with something that’s everywhere, like jeans, there are so many approaches to an object.

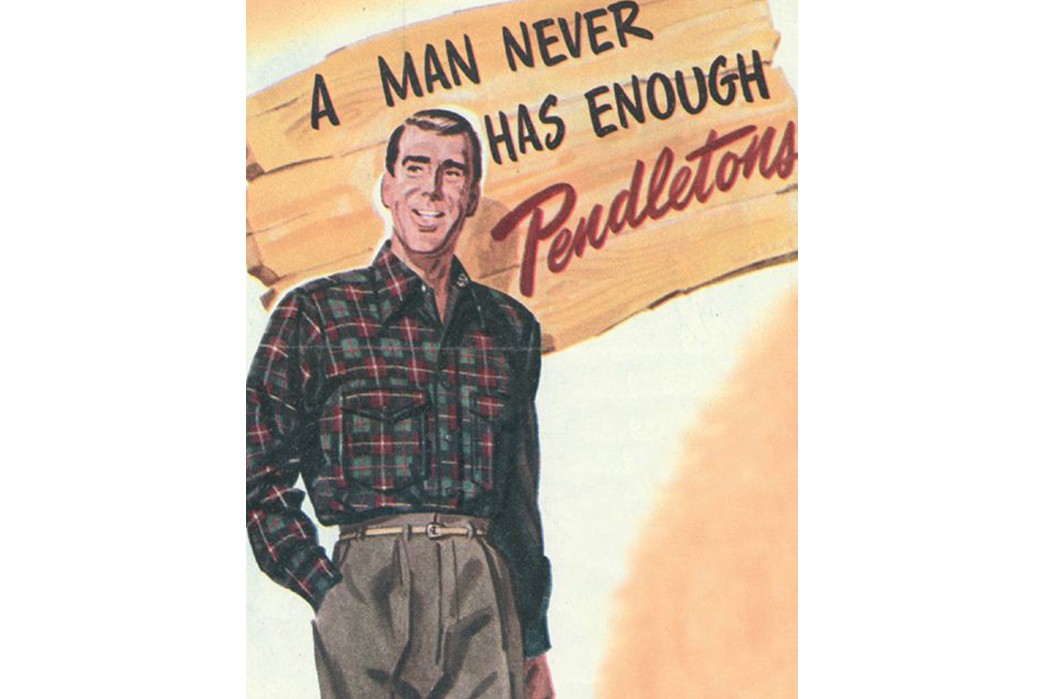

Vintage Pendleton Ad.

H: What was that like getting to access Lee and Wrangler and Pendleton? For a lot of nerds like me, that’s kind of the dream to get in there.

SA: It was a lot of fun. I dork out on that stuff. It’s also very, very different from a lot of academic or scholarly research. We’re used to an archive being like a museum, right? Where things have accession numbers, they’re organized, they’re treated and sorted in a certain way. Corporate archives is a whole different thing. And I’m not saying that because these are working businesses, right? So they have a selection of garments.

They may have started only collecting historical pieces a few years ago. Some, like in the case of Pendleton have just boxes of business records that are amazing, like office conference notes, where you can actually get back and forth dialogue and see exactly what they were thinking about what they were doing.

Many of the other ones, they just tossed that data a long time ago. From the 1940s and 1950s? They just don’t [hold onto that stuff] because it’s a working business. They didn’t really keep it. So sometimes approaching corporate archives as a scholar with very detailed and pointed questions and then just getting people to look at you and being like, “uh, yeah…” Like at Cone [Mills White Oak], I came, when the denim mill was still operating, in Greensboro and I had these very specific questions for them. And they’re like,” Yeah, we might’ve thrown that out in the seventies.” So it’s also the recovery of history. But the actual material I got to see was very cool and people who are maintaining those archives are doing some really interesting work.

H: When did you start dealing in vintage? When did that light go off for you?

SA: As a teenager just buying and selling my own stuff on eBay. But more as, like actually having my own business was here in New York, starting with the Brooklyn flea market, but then eventually just doing different vintage shows like Manhattan Vintage and Inspiration and A Current Affair and those kinds of things and having a showroom. It was something I’ve been engaged with for a while, but doing it more professionally and more specifically shopping for that kind of market was I would say about 2012 to about 2018.

H: Was that experience what began to motivate you to really write that stuff and put down kind of a firmer historical record of the clothing you were seeing and dealing with?

SA: That was part of it. I mean, the fact that I was getting all this knowledge and there were all these objects out there and no one was really addressing it in this way was really inspiring to me. I mean, we have these great image records, like the Rin Tanaka books. Right? Which I love and when I was showing those to people who were my dissertation supervisors, nobody had seen those that before.

Like that kind of compendium of all the tour jackets all the leathers. So that’s a really great image resource, but the history is tougher to trace and it’s harder to do depending on the company, but it definitely all went together with the vintage I was seeing out in the field and how I was thinking about writing it, you know?

View this post on Instagram

H: Right. And you discuss your personal network. I feel like there are these people wandering around that are these wealths of knowledge, like Rin Tanaka and people that know so much, but they’re just not writing it all down. And I fear that that was the way it was at Cone and Lee and Wrangler for decades. And now here we are trying to piece it all together.

SA: Yeah. Well, at Lee, actually, I need to give her credit because they do work with a real archivist who is a museum professional who has a master’s from University of Delaware who has set up their archive and has been a great help. She worked with me when I went there, but also just over the years, like we emailed back and forth about questions and this stuff all the time and has done great work.

But a lot of that exists in internal documents and then just interest in the way companies operate, like Lee and Wrangler Japan and Europe are very different from the way they are here. The archives are here. The historical interest is different, particularly in Japan, as you probably know. So, yeah. It gets complicated, but, but there’s, there’s a lot of good material and there’s a lot of interesting people.

H: Well not to rush you or anything and when could we expect your book?

SA: I don’t know! With academic publishing, because I have to go through peer review, they don’t just give you a pub date the way a commercial editor would, but manuscript is going to be in at the end of December. But hopefully, it’s expected in 2021, fingers crossed.

Bloomsbury is great to work with and the cool thing is that I will be getting a lot of images, which in academic publishing is sometimes a little bit more rare, but I’m hoping that what I’m doing has a little bit more range beyond just the college and university libraries. And I think, a lot of original stuff that hasn’t been published before!

As we eagerly await Dr. Abrego’s new book, you can read some of her writing at her website and stay up to date with some of her research on her Instagram.