Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

Dear reader, this is the second of a two-part piece about the hidden costs of cheap jeans. If you haven’t had a chance to read the first one, may I suggest you read it first?

For those of you who have, you may remember my casual reference to a statistic. It is the number of pairs of jeans, on average, an American owns – strikingly, it was 6.7 pairs in 2015, down from 8.2 in 2006. That statistic was initially reported to demonstrate how the sale of jeans was declining due to the growing popularity of expensive sweatpants and leggings athleisure, but it begged a different question – where did those 1.5 pairs of jeans go?

Charitable Instincts

Fig. 2 – A Cincinnati Goodwill, via Cincinnatti Goodwill.

In all likelihood, those jeans were perfectly wearable and donated to charity; a victim of a change of heart, being on the wrong side of a fashion trend, or a change in its owner’s size. If you’re like me, you’ve dragged the odd bag or two of clothing to an organization like Goodwill or Salvation Army. It’s a common perception that these donations are sold within the community to help advance the organization’s goals or distributed freely to those whose needs they meet. It feels good to think that they’ll go to help improve others’ lives – and as a practical consideration, there’s a financial benefit to those who itemize their US income tax deductions. A win all around, right?

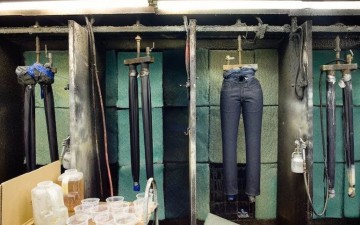

The truth, however, is much more complicated. With the increased availability of breathtakingly cheap clothing, the US market for second-hand clothing has diminished as quickly as fast fashion has risen. And, since we pay so little for these brand new clothes, we have started to think of them as disposable. The result is, we Americans donate a lot of perfectly wearable clothing – so much so that we are overwhelming the retail system these charitable organizations operate. As a result, donation centers have to cull donated property for desirability according to grades – only the top is deemed fit for local retail. It’s estimated that only 10-30% of donations make this grade – and even these get downgraded at the busiest centers if they don’t sell within a matter of weeks.

Fig. 3 – At a Salvation Army – bales of clothing destined for recycling (Jack Hanrahan, Erie Times-News)

Those donations that don’t make the sales floor? They can be earmarked for different markets on a sliding scale of desirability – a rough estimate of their residual value. In a symbol of how interconnected this system is, the lowest wearable grades are destined for places like Pakistan – a place where labor costs are so low that they produce the cheap apparel that ends up in this lifecycle. If the garment isn’t wearable, it might be destined for shredding and recycling – in particular, if it’s from 100% natural fibers such as cotton or wool. Not all materials are eligible for this fate, though, especially blended material. So a pair of 98% cotton jeans with a 2% touch of elastane for stretch, may go straight to a landfill.

The Journey Overseas

Fig. 4 – Toi Market, Nairobi, Kenya. (via Kiva Fellows)

It seems pretty simple – the supply is located in the United States or another affluent country, and the demand is located far away, often in a country south of the equator. This is where distributors come in; they buy supply from charities or for-profit companies, and offer them to importers who buy them sight unseen according to a manifest (jeans, t-shirts or bras, perhaps). These importers land the goods and then sell them to merchants (either directly or through a wholesaler), who sell direct to consumers – often at local market stalls.

It’s not always as easy as it might seem, though – some countries (notably South Africa and Nigeria) have implemented import restrictions or outright bans to try to protect their garment-producing industries. These are only as effective as the countries’ ability to control national borders, and Nigeria still ranks among one of Africa’s largest consumers of donated goods due to smugglers.

Interestingly enough, the trade routes often mirror long-standing relationships dating back centuries – a particularly fascinating example is Maharishi’s Upcycled line, where the UK-based company sends surplus Western military wear to (its former colony) India for upcycling, with the finished product returning to the West to be sold at a premium price.

Fig. 5 – Designed in England, Upcycled in India – Maharishi fishtail jacket (via DPMHI)

Can Cheap, Second-Hand Imports Be Bad for an Economy?

Fig. 6 – Bales of imported clothing being wheeled into Gikombo Market, Nairobi, Kenya (via NPR)

On the surface, it makes sense that a large influx of cheap apparel in good quality would be good news for countries that don’t benefit so much from the global economy. And certainly, many countries do make significant use of these imports – as an example, 81% of clothing purchases in Uganda are of secondhand clothes. And according to Oxfam, used clothing from Western sources constitutes more than 50% of the clothing sector (by volume) of many sub-Saharan African countries.

The key to understanding this impact, however, is this: importing goods means you’re not producing them. The net effect of the flood of donated clothing is that local industries for textiles or garments cannot compete in a local market. Africa continues to produce a lot of cotton, but its textile exports are a fraction of what they used to be. This means that its ability to develop jobs requiring advanced (higher paying) skills is inhibited, even as purveyors of inexpensive apparel utilize its cheap, unskilled labor to put together the very clothing that might end up shipped back as secondhand a few years down the line. Because of this and other pressures exerted by large economic powers, the same path that South Korea and Japan once used to bootstrap their economies is not an option for these countries.

I recently ran across a brand that summed up the predicament. It sells swimwear decorated with African-inspired prints and its name is deliberately evocative of its Nigerian-born founder’s heritage. It’s based in London and produces its garments in Asia. It seems the best way to produce a Nigerian brand may be to leave the country entirely.

Who Benefits? Putting It All Together

Fig. 7 – A World Vision Employee and a reality that will never exist, at least in the US. (Keith Srakocic, AP Photo)

It’s not just individuals who benefit from tax incentives for donating perfectly wearable apparel; every year, each major sporting league in the US produces a huge amount of souvenir apparel for the post season. To capture the immediate market opportunity for the winning team’s fans, they produce them for both the eventual winners and losers. The winners get their merch unboxed immediately and rushed onto the field or court to the players and coaches. The losers’ boxes are donated to a charitable organization in exchange for a tax write-off and are never against seen in the Western world (the NFL donated 102 pallets of clothing and other licensed products valued at $2.5 million through their partner, World Vision, in 2007).

Others who gain financially from this system include for-profit companies who license the names of charities and collect donations on their behalf. To the consumer, it appears as if the charity is running the collection and solely benefiting from the takings – in reality, the revenue is split. This isn’t necessarily dishonest; however, it demonstrates the complexity of what has been estimated to be a $2 billion used-clothing export industry.

On the other extreme are charities that are criticized for not meeting the standards to which charitable organizations are normally held (most notably, Planet Aid – a registered non-profit which has gained a reputation for diverting funds away from charity work to the point that the FBI concluded that “little to no money goes to the charities” upon investigation). And beyond that, there is a growing trend of donation boxes fraudulently posing as charities.

All of this is getting so widespread I found a highly dubious donation box within a mile of my house without even looking for one – the charity’s name is licensed by its ostensibly non-profit operator, which pays out an eye-raising 40% of its operating budget to its Chairman and CEO.

Fig. 8 – A highly dubious donation box.

A Self-Perpetuating Cycle

It’s easy to think of fake charities and other profit-motivated actors as con artists preying on an unsuspected public, but what fuels this second-hand clothing industry is the constant supply of discarded apparel that we are generating. It’s like karmic hush money paid by our conscience – we drop something in a bin, pat ourselves on the back and then never have to think of it again. But karma has a way of coming back in unusual ways; NPR’s Planet Money relays the remarkable story of someone who donated his lacrosse jersey to Goodwill and found it at a market in Sierra Leone months later. What struck me most is how he had seemed to cross a boundary he wasn’t supposed to, like Bran Stark connecting a young Hodor to an ominous glimpse of his future.

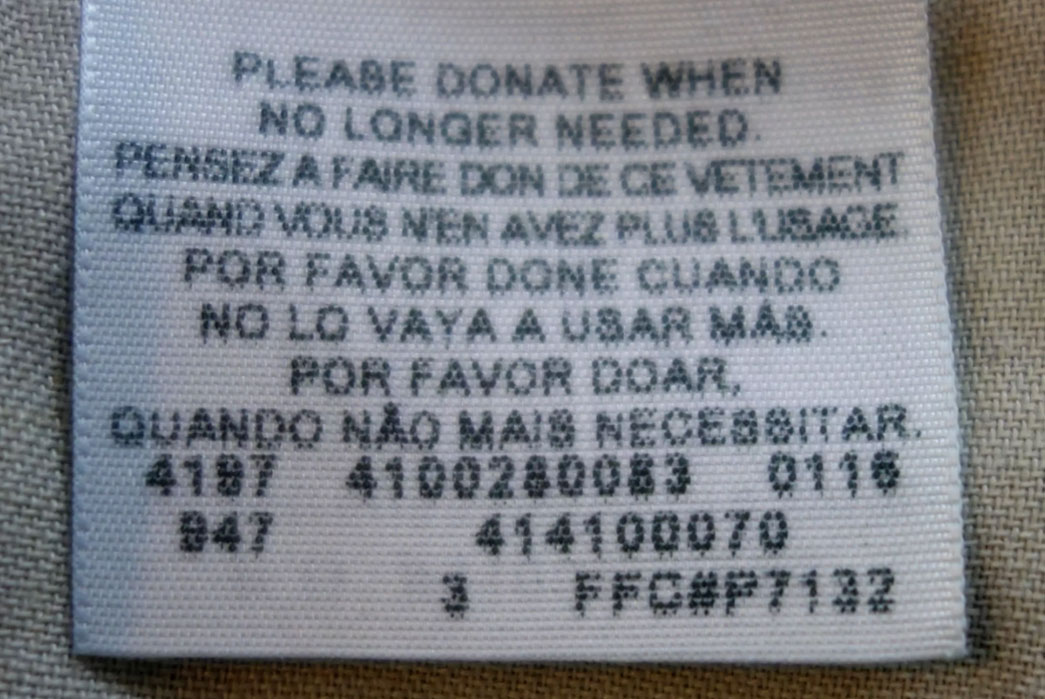

What’s become clear to me is you cannot unlink the poverty of garment factory workers making cheap apparel from the used clothing that eventually gets shipped back. The cycle is so interdependent that a pair of cheap jeans I bought while researching this piece comes with a tag: “Please Donate When No Longer Needed.” They were made in Lesotho and seem to have been fated at birth to return to the continent of Africa some day. It’s given me pause to consider my own prolific, sometimes impulsive, purchasing habits – this rapid-fire cadence of obsolescence acquiring the sheen of the obscene.

I don’t mean to suggest the answer is not to consume anything – although buying less and using what you do have more is a step in the right direction. And certainly, there are those who rely on affordable clothing, whether new or used. I think of it sort of like fast food – something seemingly cheap that turned out to have less obvious social costs due to its health impact. And now consumers are demanding better, healthier food – and are willing to pay more up front for it. I look forward to the day that we’ll come to understand cheap clothes in similar terms and challenge companies to give us more ethically sourced options that we consume more responsibly. Because the world is a small place and our choices have consequences.

References

I can’t emphasize enough how much this piece owes to the following (whose references I have made liberal use of). In particular, Clothing Poverty is filled with detailed examples of the deeply enmeshed economy of secondhand clothing and situates it within both an historical and contemporary social context:

- Elizabeth L. Cline, Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion (Portfolio / Penguin, 2012)

- Andrew Brooks, Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-hand Clothes (Zed Books, 2015)

- The True Cost, directed by Andrew Morgan (2005, Life Is My Movie Entertainment), Netflix stream