Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

Wine is amazing – it’s an endless source of discovery and pleasure that makes me realize just how huge this world is and how much fun it is to explore. I always enjoy finding a special bottle and sharing it with someone who has an appreciation for drink and is also thrilled to have new experiences.

If you haven’t had a chance to get your bearings in it, the world of wine can also be a little intimidating – it reminds me a lot of raw denim in that way. This site has done a great job in demystifying the terminology and “how to’s” of raw denim and for those of us who have taken the plunge, I think we’d agree it was worth the learning curve.

So, in that spirit, I thought I’d talk a little about natural wine, a wine-making philosophy that is getting some much deserved attention – I suspect it will resonate with readers of this site and column. I’m not a wine expert by any stretch of the imagination, but natural wines are so fun – they can be elegant, feral or downright funky, and adhere to principles that many of us can connect to. They also challenge our perceptions of what wine can be, especially with respect to white wines.

Fig. 2 – Wine Grapes (via domodimonti.com)

So what is natural wine? It’s not something that everybody agrees upon 100%, so I’ll talk about some of its principles. They relate to how wine is made, so in almost ridiculously simplified terms: wine is made from grapes that are harvested from the field and then crushed or pressed. This initiates a fermentation chain in which yeasts convert the fruit’s sugars into alcohols, followed by a secondary bacterial fermentation (which is harder to explain, but is a significant factor in the way the final bottle of wine tastes). After fermentation, wines can be “matured” in barrels (or not), then filtered (or not) and bottled. Winemakers can age the wine further in the bottle before they think it’s ready for release.

As wine production has become industrialized, there are a number of ways winemakers have developed to “help” this process: pesticides, mechanical harvesting (to help with larger yields), the addition of commercial yeast strains (required if you killed all the indigenous yeasts by administering pesticides or washing those pesticides off), adding sugars (to boost alcohol content) or commercial bacteria, and the addition of sulphur dioxide to help slow fermentation at any of the wine-making steps.

Natural wine makers adopt most of the following principles: their grapes are grown free of pesticides (by organic principles and/or biodynamically) and harvested by hand to preserve the quality of the fruit. They prefer wild yeasts on the skins of the grapes (that help define the regional character of the wine) instead of commercial yeasts. They don’t add sugars or bacteria (which are artificial short cuts – added sugars might be the Botox of wine) and use sulphur dioxide scarcely, if at all. Natural wine makers usually avoid filtering the wine, which removes the bacteria and enzymes – the biome that is so integral to the final expression of the wine. This part may result in a harmless natural sediment in the bottle, so don’t be surprised or grossed out by it! Filtration is like the sanforization of denim, it can inhibit the great, natural expression of the finished product.

To summarize, the goal of natural winemakers is to preserve the local character of the wine (you’ll often see the word “terroir” used in talking about wine. This is what it means – not just the soil, but the climate, micro-organisms, etc. – that all contribute to what makes a wine unique), to use responsible and sustainable agricultural practices, and to make wine with minimal intervention.

Fig. 3 – The vineyards of Frank Cornelissen, on the slopes of Mount Etna (via sedimentarywines.com)

Making wines naturally is a lot of extra work, but can yield a special product. Here are some of my favorite wine makers working in this style. It’s by no means comprehensive – I’ve tried to keep it relatively affordable and focus on producers that are relatively well distributed. I’m also a little biased towards old world wines, but there are many American winemakers worth looking into – a few that stand out in my mind are Ruth Lewandowski (based in Salt Lake City), Dirty and Rowdy, and Kalin Cellars.

Before we start – I’ve tried to avoid wine nerd terminology but in some cases it’s unavoidable. So a mini-glossary:

A varietal is a species of grape from which wine is made – for example, Cabernet sauvignon or Chardonnay.

Winemakers usually make different bottlings – whether from different varietals, special blends (sometimes called reserves when made from particularly high quality grapes) or vineyards. These are called cuvees and are analogous to the models that a carmaker makes.

Tannins are a slightly bitter artifact of making wines with skins on (skin contact) – it’s the same taste of a tea you’ve accidentally brewed too long. Red wines become red due to skin contact but it’s not impossible to make white wines with an extended skin contact – sometimes this imparts an orange color to the wine (making an orange wine, which has emerged as a separate category to red, white and rose).

Gravner

Fig. 4 – Josko Gravner in the cellar – the amphorae are buried underground with their lids open (via: nonsolodivino.wordpress.com).

Located in Friuli, in the Northeastern corner of Italy on the border near Slovenia, Josko Gravner’s estate is an icon for the rebirth of an ancient way of making wine. He trained as a conventional wine maker but renounced that path after visiting California in 1987 and becoming alienated by the amount of chemicals that region was putting into their wines. This put him on a path of historical research, which led him back to the Caucasus, now a part of the post-Soviet country of Georgia. It’s one of the oldest wine-producing regions in the world, with a 6,000 – 8,000 year history of making wines. One of his discoveries was their use of large clay pots (amphorae, or anfora in Italian) to age wine (instead of the relatively modern practice of using barrels). He buried his amphorae in the ground, which allowed for the same development benefits of barrel aging without imposing the flavors of wood.

After his first trip to Georgia in 2000, Gravner started to produce wines in that style back at home – lush, complex white wines that are some of the most amazing I’ve ever had. A bottle of his early 2000s Ribolla Gialla Anfora could redefine your idea what wine could be, nectar and exotic spices with a structure not often found in whites. His wines aren’t the cheapest (partly because he doesn’t have an entry level wine and partly because he cellars them for years before releasing – his latest release seems to be the 2005 vintage), but they are well worth the splurge. He is phasing out his blended Breg Anfora in favor of a wine made exclusively from Ribolla, a native grape to the region, which is something I agree has reached a greater level of transcendence.

Other notable and more affordable (and findable!) wine estates working in the area are Radikon (near Gravner) and Movia (across the border, in Slovenia).

Frank Cornelissen

Fig. 5 – Frank Cornelissen (via Goblin Mag)

Located on Mount Etna on the Italian island of Sicily, this is a relatively new estate that since 2001 has produced wines that are singular and extreme (and quite delicious). He pushes the envelope of non-interventionist practices, avoiding any kind of treatment (chemical, organic, or biodynamic) unless absolutely necessary and does not use sulphur dioxide, meaning each bottle is a living, breathing organism. Because of this approach, each vintage is a unique expression so it’s always amazing to taste a new release.

The red you’re most likely to encounter is Contadino, which can be immensely powerful with touches of finesse. But do look out for his Susucaru rose. It’s made with skin contact and is super concentrated – it’s like a really intensely deep red wine but tastes like pure freshness. It’s far from your typical summer guzzler and it’s the best rose I’ve ever had.

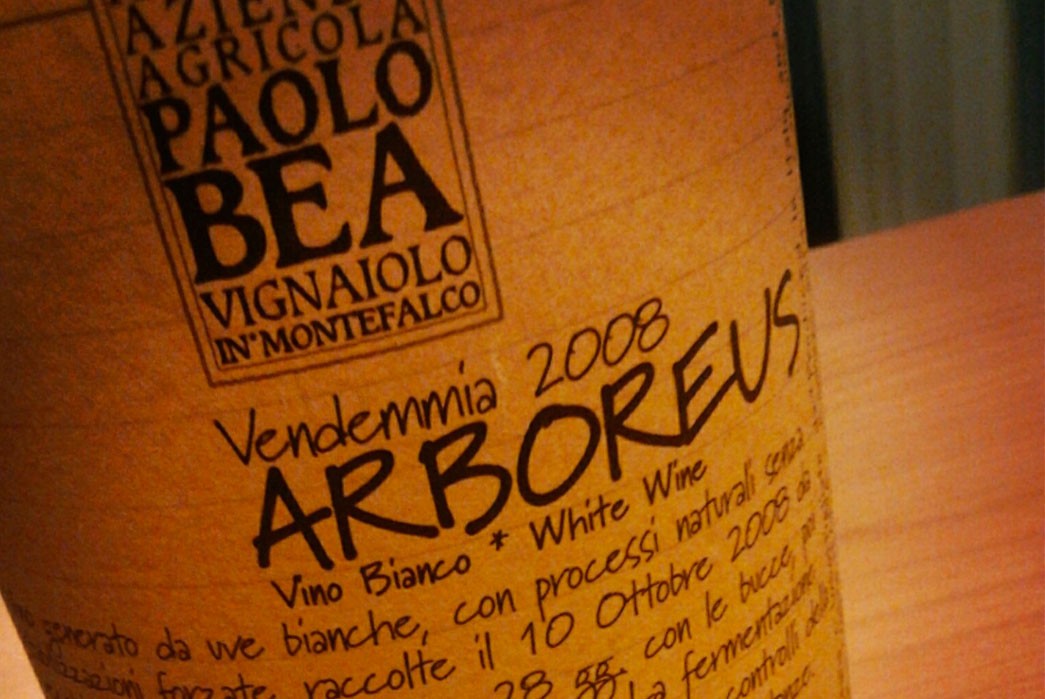

Paolo Bea

Fig. 6 – The wine from Paolo Bea that made me reconsider what wine could be (via gliamicidelbar.blogspot.com)

Located in Umbria, next to Tuscany in the heartland of Italy, where Paolo Bea has been a steward for the preservation of terroir – his family has been making wine for half a millennium. When you think of Tuscan wines (such as those from Chianti), you often think of the sangiovese grape. While there are many fine examples of wine made from that grape (hello, Montevertine!), Bea has chosen to focus on another grape native to the region – Sagrantino, which is an intense, highly tannic grape.

His wines are made with the same principles of non-intervention and often have a wild, animalistic character. His most affordable sagrantino cuvee is the Rosso de Veo, which balances the wine’s savage character with enough elegance to grab your attention. His labels are printed from handwritten copy, which explains that he does not provide wine samples to the trade, “out of respect for our mutual professions.” He embeds the principles of natural wine to the core of his business, which I deeply respect. Non-intervention indeed.

I am biased towards his whites – his Arboreus 2008 was a wine that caused me to reconsider the possibilities of wine, with the flavors of intensely ripe peaches, lavender, honey, and cinnamon.

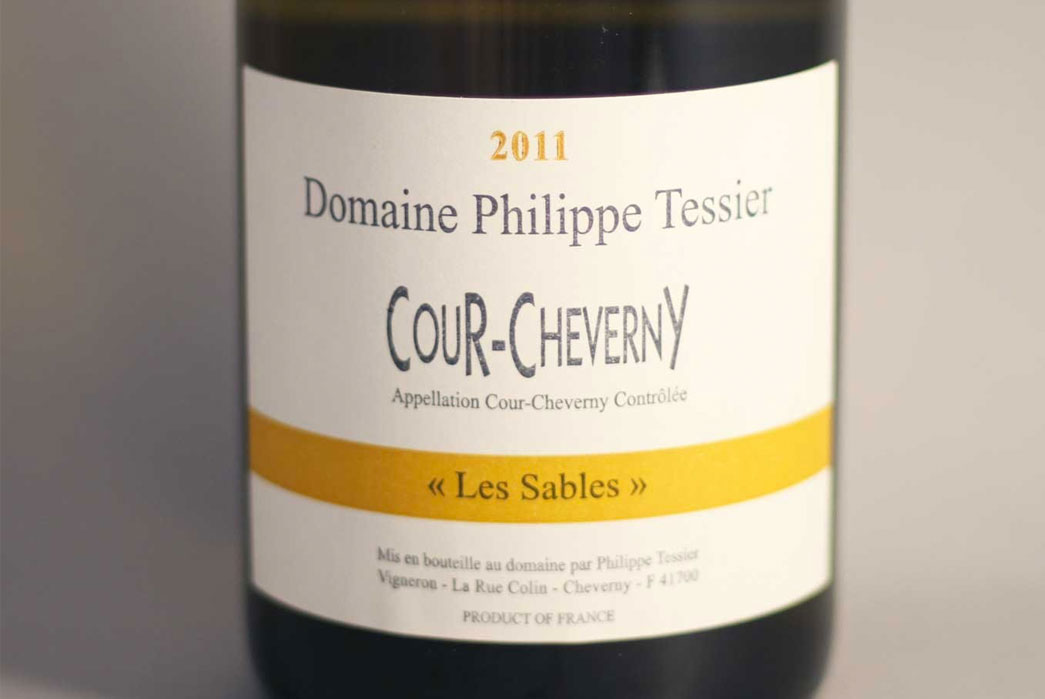

Domaine Philippe Tessier

Fig. 7 – Tessier, Cour-Cheverney (via domainela.com)

Tessier is another relative newcomer. His estate is located in the Loire River Valley in central France, which is known for its white wines (including the popular Sauvignon blanc and the underrated Chenin blanc – think of a sliding scale between Chardonnay and Riesling and you’re almost there). He is one of my favorite producers and a nice counterbalance to some of the other, wilder natural wines I’ve written about.

That said, he adheres to the principles of natural wine and his wines remain really affordable. His red wines are made from Pinot Noir and Gamay (the grape that gives Beaujolais its character) and he makes a white wine blend from Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay. But it’s his use of the obscure Romorantin grape in his Cour-Cheverny that really captured my attention. It’s beautifully made, tasting of orange zest with a hint of cinnamon and licorice, but tastes incredibly fresh. It’s both nerdy and accessible.

These producers represent a kind of new school of natural wine, but I also want to recognize two wine estates that have held the same principles by preserving long-standing wine traditions of their region.

Chateau Musar

Fig. 8 – Chateau Musar. Note the orange hue of the ’69 white (via Chambers St Wines)

This estate was founded by Gaston Hochar east of Beirut in 1930, in the Bekaa valley of Lebanon. Their wines are made consistent with natural wine values and are probably unexpected for anyone who thinks of old world wines as being European. Like Georgia, Lebanon is another ancient wine-producing region, with practices dating back thousands of years. The reds are produced from wine varietals associated with France and are pure muscle – full of spice and vigor and built to age as much as any wine from France. I feel bad about drinking any current release because of their aging potential – a more affordable cuvee that’s ready to drink now and representative of Musar is their red Musar Jeune.

Like many of the other producers I’ve written about, I’m obsessed with their whites. Their recently passed winemaker, Serge Hochar, once characterized his whites as his “first reds” and “more serious” than his actual reds. His principle was to let nature do its thing and the wines are made with wild yeasts and low use of sulphur. The whites are made in an oxidative style, meaning they are exposed to more air than is usual to create a complex, umami taste. It’s often thought of as a flaw, but when used properly adds another dimension you wouldn’t normally think of belonging to wine.

Lopez de Heredia

Fig. 9 – Don Rafael López de Heredia y Landeta, the founder of Lopez de Heredia. (via Lopez de Heredia.com)

Of the Spanish winemaking regions, Rioja is one of the most well known and its establishment dates back to the nineteenth century, when an insect blight (phylloxera) on French grapes caused that country’s winemakers to look further afield for fruit. Lopez de Heredia is one of the three oldest winemakers in that region and is still family-owned. They make an unsurpassingly elegant red wine (the Riserva in particular is an unbelievable wine for the amount of money you’ll pay for it – the Cubillo is more affordable, but less special – I’d hate for you to form a judgment on this winery based on that). They also make a white wine that is one of the world’s great whites. The white is made from native Viura and Malvasia grapes and is aged in oak barrels consistent with a largely abandoned tradition for white Rioja. It’s a miraculous way to treat Viura – it imparts a toasted nuttiness that’s simply incredible.

Their white riserva is made in an oxidative style, a story told by its rich gold color. It’s well balanced, complex and approachable with an almost perfumed bouquet with hints of mushroom, forest floor and creme brulee. As with Musar, their whites are on par with (and may even surpass) their reds.

You’d think doing things in this way would result in an expensive wine, but you’d be surprised. Wine prices are often set by supply and demand and this is still a niche part of a huge, global business. If you’re looking for a good wine priced less than $10, this probably isn’t the right place to look – while there are wines with integrity available around that price point, it’s often the same kind of conundrum you’d face looking for a $20 pair of jeans.

I’ve tried to focus on wines that I think are great value and represent natural wines at their peak. They may cost more than you’d prefer to spend on a bottle, which is totally understandable. Happily, there are plenty of other options out there.

Which raises an important point – there really isn’t any substitute for going out and drinking these wines. It’s not quite digging ditches but might be tricky to get started. If you’re interested in pursuing natural wines, I’ve included a list of wine stores and one wine bar below, followed by some importers you might want to remember. As a caveat, I’m sure there are dozens of great wine stores across this country that are taking natural wine seriously – I am not in the wine trade so apologies if I’ve overlooked an amazing store. If so, let me know in the comments!

Fig. 10 – Uva Wines (via yelp.com)

Europa Wine Merchant (Portland, OR) – I ran across this wine store while looking to stock my bar at the nearby Ace Hotel. Its owner is incredibly knowledgeable and is happy to walk you through his tightly curated selection. As a bonus, you get to find all sorts of amazing Oregon wine that you’d be hard pressed to find outside the Pacific Northwest.

Four Horsemen (Williamsburg – Brooklyn, NY) – This might have been the United States’ first wine bar devoted to natural wines, and takes its mission pretty seriously. It’s owned by James Murphy (LCD Soundsystem) and seemingly patterned after a new wave of wine bars in London (I’m thinking Sager + Wilde) – he is the most reluctant of rock stars, which is demonstrated by the down to earth, highly educated service at this bar. They also serve a limited menu of on-point food.

Frankly Wines (Tribeca – New York, NY) – This store isn’t focused on natural wines per se, but owner Christy Frankly is obviously interested in finding obscure, delicious wines wherever they may be. Her staff are really helpful and will be able to find a wine to meet your needs at whatever price point you’re looking for.

Red & White Wines (Wicker Park – Chicago, IL) – I wandered into this store en route to a friend’s apartment and instantly felt at home. A great selection and friendly staff.

Uva Wines (Williamsburg – Brooklyn, NY) – Potentially the first New York wine store to specialize in natural wine, under former wine buyer (and musician) Justin Chearno, who is helping to run Four Horsemen. You might find a bit of New York attitude, but if you convey that you’re open to new experiences, there are many fine options here.

Wine Bottega (Boston, MA) – a small shop in the South End of Boston, owned by Matt Mollo, who imports wines as SelectioNaturel.

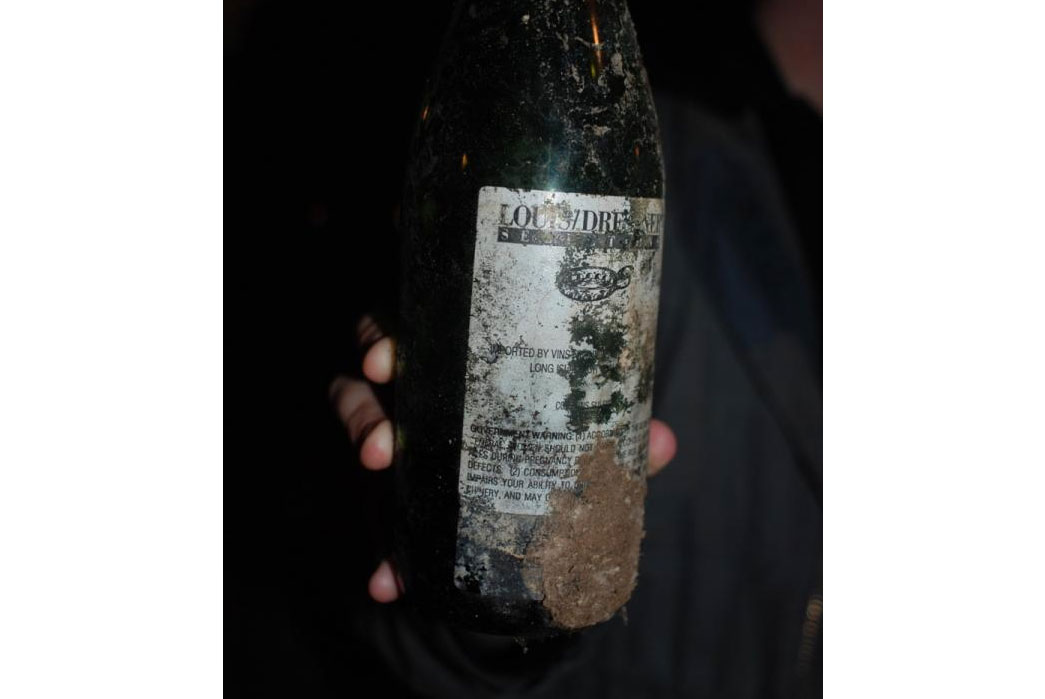

Fig. 11 – Louis / Dressner import label (via Louis Dressner)

Still looking for more? Here’s a handy tip – often times an importer will put their label on the back of a bottle of wine. Once you’ve found that a particular importer has established a track record with you, this can be a good way of recognizing that it might be worth drinking a bottle of wine that you otherwise know nothing about.

With respect to natural wines, Louis / Dressner, Rosenthal Wine Merchant, Selectio Naturel, and Zev Rovine have earned my seal of approval.