It’s a universally recognized fact that we humans look to other people’s footwear on first impressions. And, as silly as it might sound, studies have shown that we’re able to ascertain quite a bit of information (albeit relatively superficial) about someone’s external and internal characteristics just by looking at their shoes. So why do some of us choose to splash out hundreds of dollars on footwear? Some do it just for aesthetics, some for comfortability, some for durability and longevity, and, for a most, it’s probably a mix of these in addition to a few other factors.

In a world of apparel and footwear enthusiasts, there are endless options and opinionated obsessives and I believe it’s important to remind ourselves why we make the decisions we do. I like to think sharing information enables power. I’m also an advocate of craft and quality, so naturally I like to inform you of the options on the market, making it easier to choose the appropriate construction on your next footwear purchase. Hopefully sparking an interest in some, keeping the fire burning in the rest, and thus keeping traditional craftsmanship alive for many centuries to come.

Constructing fine footwear is still a very detailed process and not one you can easily wrap your head around if you’re not already an enthusiast or in the shoe business. If you are not able to visit a shoe factory to see the process in action, but would like to learn more about how fine footwear is made, I would highly advise some production videos on YouTube to get started. I’m partial to this one showing the process at one of the UK’s most prestigious footwear brands, John Lobb:

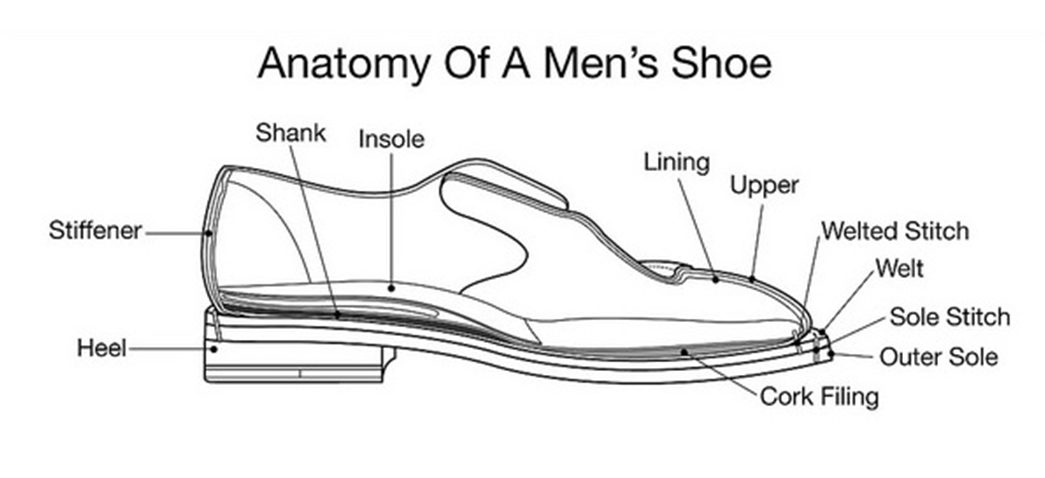

Shoe Anatomy and Terminology

To keep you on your toes, we should start off with some basic footwear anatomy and terminology (if you’d like more detail, check out our complete shoe rundown). One of the most important terms is the welt, which is a narrow strip of material holding the shoe together. Traditionally the welt is made of leather, but it can be made of rubber or plastic too.

The welt also acts as a gasket between the upper and the sole. On a “true welt construction” the welt is attached to the feather of the insole. The feather is the curve around the edge of the insole where the upper is attached. Some construction methods don’t make use of a welt like Blake construction.

Anatomy of a men’s shoe. Via RMRS.

Just to get off on the right foot (yes, there are quite a few foot-oriented puns, and I intend to implement as many as I can get away with), I’ve done a rough explanation of the three key steps in any method of shoe construction.

Steps in shoe construction:

- Insoling – Attach insole to bottom of last

- Lasting – Upper shaped to last and insole

- Bottoming – Sole is attached to upper (this step will largely determine quality, performance and thus the price of the finished shoe)

The method for how the sole of the shoe is attached to the upper is the crux of what we’re talking about today. Because the sole is the part of the shoe that makes contact with the ground, it’s usually what wears out first. The way the sole is attached often determines whether it can be replaced and subsequently if the shoe is still wearable.

The soles of most shoes these days are simply glued in place, which makes it nearly impossible to swap in a new one without significantly damaging the upper. Most higher end shoemakers, however, use more complicated techniques that allow a cobbler to replace the soles and have (at least the bottom part of) the shoes good as new. The following explain the history and methods behind the most common of these techniques.

We’d also like to thank Nghia Hoang of the Vietnam Raw Denim Facebook group for the use of his educational illustrations.

Blake Construction

The Blake construction was invented in 1856 by Lyman Reed Blake, an American inventor who specialized in shoemaking, and it’s the oldest mechanized method in the field. Blake himself worked for Singer Sewing Company in its very early days, setting up machines, but went on to become partner in a shoemaking firm, where he helped mechanize and speed up the shoemaking process, most noticeably with the invention of a sewing machine that was able to sew the sole to the upper.

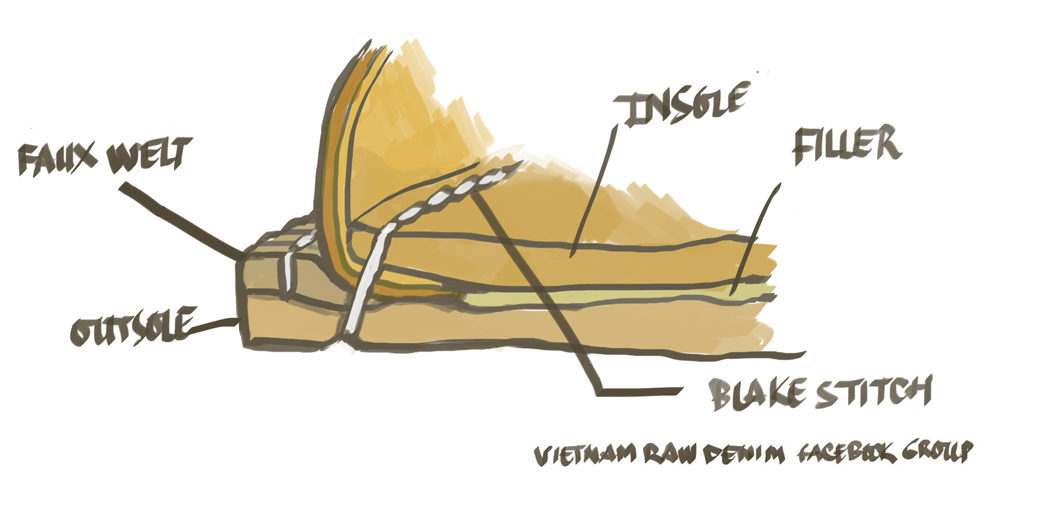

He first, however, had to design a shoe that could be made from this method. As I mentioned earlier, the Blake construction doesn’t actually make use of a welt, but is instead held together by a stitch (rightly named a Blake stitch) which runs through the insole and upper to the outsole, i.e. the bottom of the shoe. It is a product of the Industrial Revolution as it is impossible to do it by hand, because the primary stitch goes straight through the insole.

A cross section of a Blake stitched shoe via Pinterest.

Considered the original, mechanized method of shoemaking, Blake has a very loyal following in Italy, favored by traditional shoemakers for its elegant, slim silhouette, as well as for its flexibility, due to there being no welt. However, the Blake construction does have its drawbacks when it comes to sturdiness. Due to its relatively primitive construction and the fact that there’s a thread running directly from the insole to the outside of the shoe, the Blake is less ideal for harsh weather conditions than the other methods listed. Some find the stitch in the insole irritating, but this can be covered up with a lining or an additional insole. But on the plus side, this method does improve the shoe’s ability to transport heat and moisture out of the shoe, should you perspire from your feet. It’s possible to resole a Blake constructed shoe, but one has to rely on a Blake machine to do so, making it a difficult task for many modern day cobblers.

The Blake’s loyal following seem to prefer the shoes for their slim aesthetics, which makes for an elegant appearance that ties in well with classic tailoring. The designs of British high end fashion and tailoring company, Paul Smith, for instance, make frequent use of Blake construction on much of their Italian-made footwear, and generally, this construction method is found in Italian-made footwear intended for suiting. But for workwear and other outdoor performance footwear, the method is less relevant. Many workwear enthusiasts seem to dig the chunkiness of other, more sturdy construction methods.

Blake Rapid Construction

This construction is an expansion of the traditional Blake construction, implementing the Sutton Rapid outsole sewing machine, which was invented by Roy Sutton and Jerry Mueller more than a hundred years after Blake invented his original machine.

The Rapid stitcher helped speed up the process for shoemakers around the world, and this machine is still the preferred outsole stitching method for most shoe construction methods, including the popular Goodyear construction.

A Rapid stitch used in conjunction with a Goodyear welt. Image via Red Wing Heritage.

As you can see from the illustration, this innovation allowed for an extra outsole to be put on, for further weatherproofing, durability, etc., but also makes for a wider and chunkier appearance than the traditional Blake construction.

Paul Smith Ernest is done by Blake/Rapid construction. Notice the visible Rapid stitch on the outsole as well as the midsole. Made in Italy. Via Paul Smith.

Naturally there are many similarities between this and the traditional Blake, and the same brands and industry people that prefer the Blake method typically make use of the Blake/Rapid construction too, as it is an updated version of the original. Paul Smith makes use of both traditional Blake construction as well as the Blake/Rapid, which is visible in their Ernest shoe.

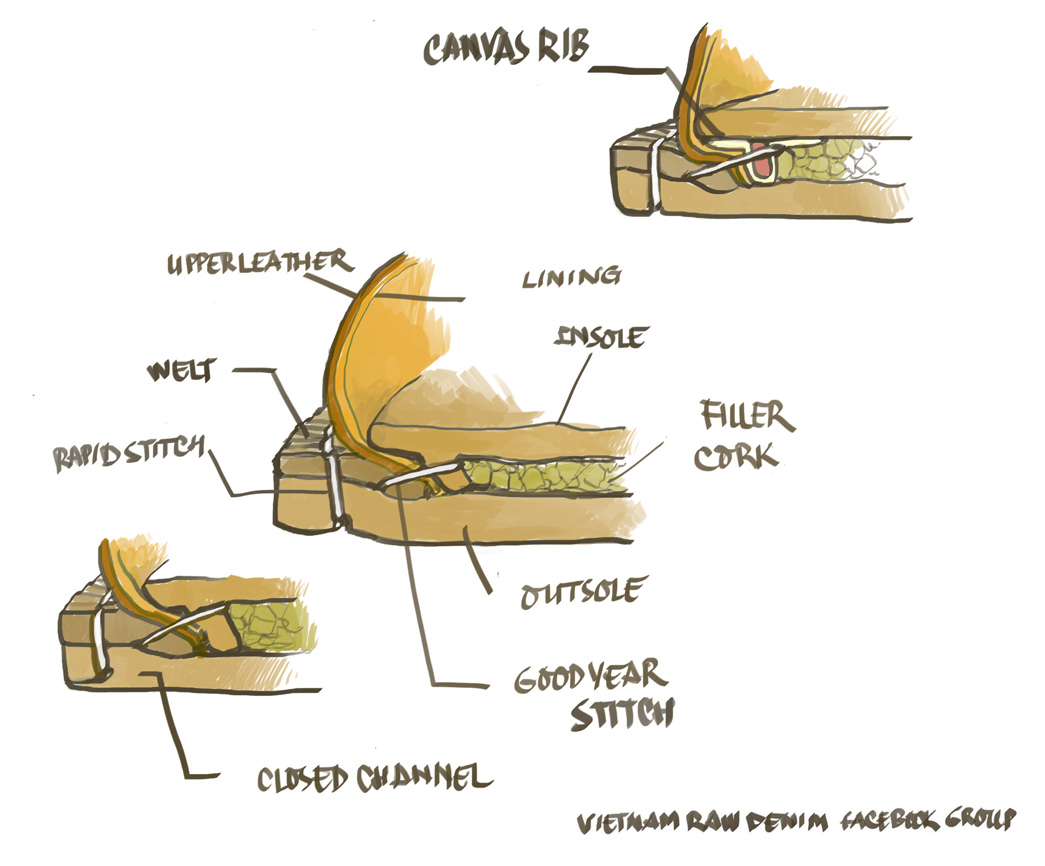

Goodyear Construction

The invention of the Goodyear construction didn’t come long after Blake, but there seems to be some confusion around who actually invented what and when. From what I’ve read, I’m hesitant to give all the credit to Charles Goodyear Jr., the son of Charles Goodyear — the forefather, one could say, of vulcanized rubber shoes.

In between the initial attempts and the actual “modern” process of Goodyear welted shoes, a lot has happened in development of machinery. The actual inventor was August Destouy around 1860, who patented the process in 1862. He then sold the patent to James Hanan, a New York shoemaker, but Hanan had so many mechanical difficulties that he eventually sold the rights to Charles Goodyear Jr., who once again assigned Destouy, as well as an English mechanic, Daniel Mills, to further perfect the machinery. A lot of patents were filed in the subsequent ten or fifteen years, until Goodyear finally had his name tied to the invention with a patent published in the fall of 1875. The machinery has continued to develop ever since.

Welt visible in a bisected pair of Red Wing Iron Rangers near the very tip of the toe.

As you can see from the illustration, the Goodyear welting process is a bit more intricate than the earlier Blake methods, as it makes use of a new type of machinery, one able to make a curved stitch through the upper, insole and the newly implemented welt.

Modern Goodyear welting also makes use of the Rapid stitch, keeping the welt, midsole and outsole together, which makes for a sturdy construction. There is no stitch on the insole so it’s more weatherproof than the Blake construction. Also, it’s possible to do the welt stitch by hand which makes for an easier resoling process than with the Blake method. Many popular heritage and outdoor shoe brands — like Heddels favorites Red Wing, Alden, etc. — make use of the Goodyear construction.

Storm/Norwegian Construction

Paraboot Michael shoe is constructed with a Norwegian welt construction. Notice the two exterior rows of stitches and the nicely detailed storm welt, which is both decorative and functional on this example. Image via Rakuten.

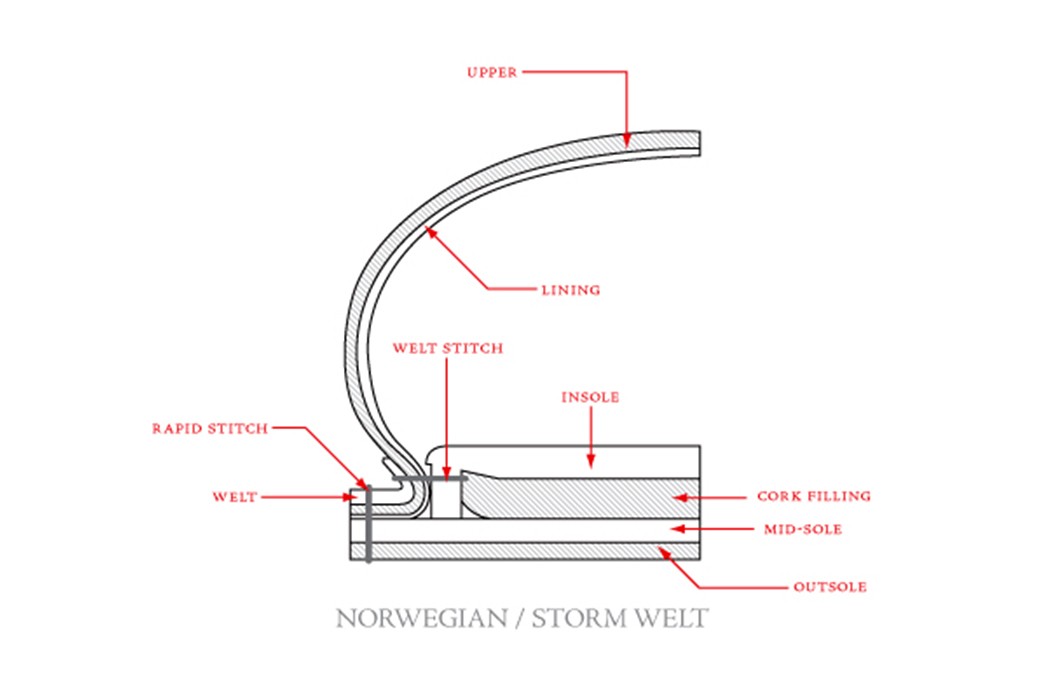

Norvegese, or Norwegian, construction has its origins in Italy, and was initially intended for making outdoor shoes more waterproof. Norwegian is a family of construction methods that are a more or less elaborate versions of the original Norvegese construction which, like the Blake, didn’t make use of a welt at all. What separates this construction is that instead of attaching the upper to the feather of the insole, the upper is turned outwards and runs parallel with the outsole. As opposed to Goodyear, which has only one exterior stitch, Norwegian constructions have at least two, which are the basis of the construction: the outsole stitch, holding together the upper, midsole and outsole, and the Norwegian stitch, traditionally just keeping together the upper and insole.

The Norwegian welt illustrated. Via My Denim Life.

Several iterations were lined with silicone to further protect them from water, and later elaborations on this method include the Norwegian welt construction, which implements what some would refer to as storm welt (more on that below) and additional cork filling. These features makes for a sturdier and more waterproof shoe with added comfortability, but it also makes for a chunkier look and more extensive, and thus more expensive, construction.

French footwear brand Paraboot (pictured), makes use of the Norwegian welt construction. Many Italian virtuosos still make use of traditional Norvegese construction in some very serious attempts at what one could dub as Shoe Art. In what seems like antipode to the traditional Blake construction, these shoemakers are happy to make use of up to four rows of exterior stitches in these extravagant creations, often implementing braided rows of stitching, as means of decorations and to show off their technical abilities.

Norvegese custom painted Italian shoes from Bettanin & Venturi. Notice the many rows of stitches and wide sole.

Storm welting is its own method, but it borrows elements from both Goodyear welting and Norwegian, and can be executed either way. Some file it under the same category as Norwegian, and, I believe, that’s where it takes its origins from, but it’s constructed with the goal of making the finished shoe even more waterproof.

One could (and probably would) argue, that Norwegian constructed shoes are storm welted, seeing that they have an elongated welt which is molded up against the bottom part of the upper, to form a seal to prevent water from entering. What then separates Norwegian from Storm, is that Norwegian construction makes use of exterior stitching only, whereas storm welted shoes are typically made from a Goodyear construction, and as such, they’re built with only one exterior stitch: the Rapid stitch on the outsole.

Stitchdown/Veldtschoen

Veldtschoen — from Afrikaans or Dutch, which simply translates to the English field shoe — and in its technical form, known as stitchdown, is, in its traditional form, one of the world’s oldest footwear constructions, dating all the way back to the seventeenth century.

It originated in Cape Dutch of South Africa, at a time when the region belonged to the Dutch and the veldtschoen served as a primitive bush shoe. Traditionally constructed from untanned game hide, the upper is traditionally flanged outwards and then stitched down onto a midsole and outsole. The construction holds a special place in southern African footwear industry, but was helped made noticeable and internationally famous by Clarks of England, known for their classic Desert Boot from 1950.

Clark’s famous Desert Boot. Image via Google.

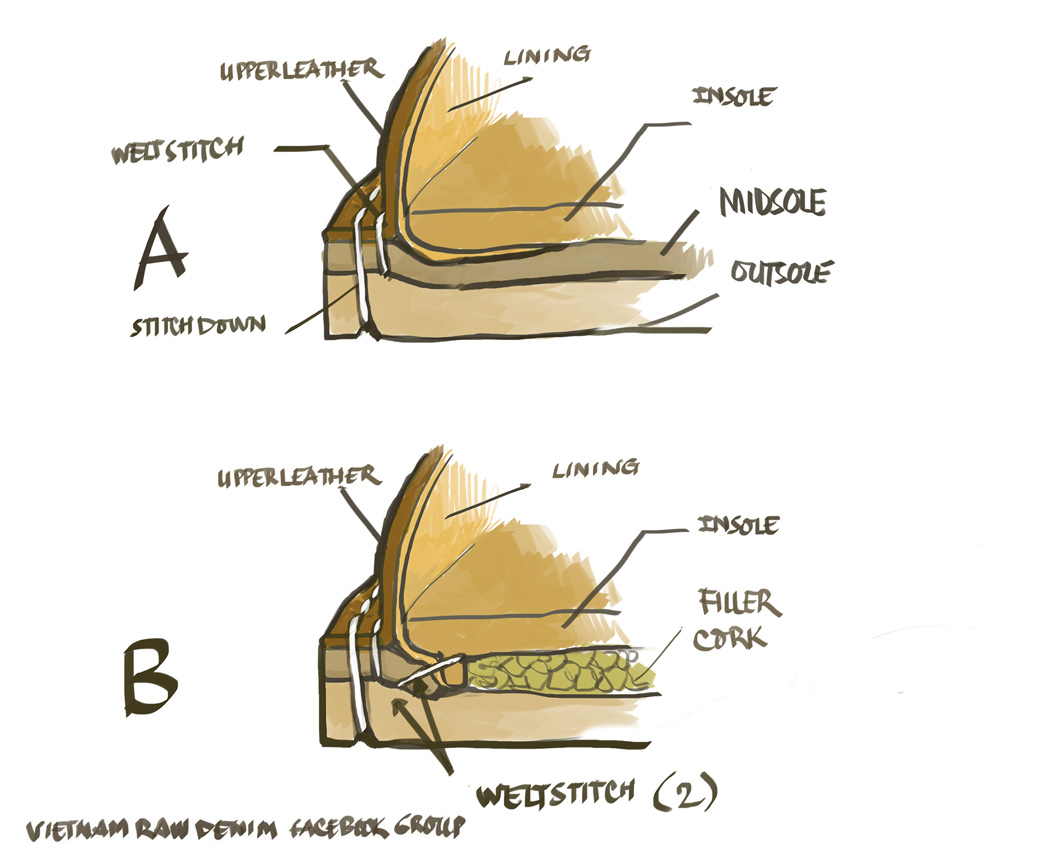

Like the rest of the methods, the Stitchdown construction has evolved with modern day innovation in machinery, so now, a contemporary Stitchdown-constructed shoe will typically make use of both a Goodyear-welting machine and a Rapid stitcher. The typical distinction with a Stitchdown is similar to that of a Norwegian constructed shoe, because the upper is flanged outwards and sewn to the mid- and outsole.

The construction methods are what ultimately separate the Stitchdown from the Norwegian. With a stitchdown-constructed shoe, the lining is typically welted onto the insole before the upper, which is subsequently sewn onto the mid- and outsole, and thus connected to the welt with two separate stitches.

Wesco Jobmaster made from the Stitchdown construction. Image via Life Time Gear.

Unlike the Norwegian, but similar to the Goodyear construction, the welt stitch is not visible from the outside of the shoe, and the two exterior stitches are both connected to mid- and outsole respectively, making for a sturdy construction often used in hard wearing work boots, like the American Wesco or Canadian Viberg. As with the Desert boot, it’s not always common to make use of two Rapid stitches, and some brands prefer the use of adhesive tape instead of or in addition to the stitching. The basis of the construction remains the same though.

Conclusion and Comfort

A punch-cap toe on a pair of stitchdown White’s Boots. Image via DenimHQ.

Many enthusiasts have strong feelings about which construction method is to be preferred. Goodyear constructed shoes are easier to have resoled than Blake, but if you’ve spent several hundred dollars on a model, the retailer will usually (and the maker almost always) offer some sort of resoling option relevant to the initial construction method, and I have, as such, never encountered any problems upon getting a new sole for either a pair of Goodyear or Blake constructed shoes.

Aesthetics and tradition also play a role in which option people prefer, just the same way that Italian makers (and Europeans in general) prefer methods that originated in their region. The Stitchdown, for instance, is popular in England and Holland, whereas American makers will typically prefer construction methods stemming from their region, such as the Goodyear construction. I have yet to see an infallible field test (and consequent breakdown of how each construction performs in harsh weather conditions) but I’ll generally say that storm welting is a good option for anyone wanting to use their shoes in rain and snow. Additionally, adding a chunky outsole, raising the level of the shoe from the ground, as well as adding grip, will certainly help those wanting to hike in mud or over hilly terrain.

Assuming we’re comparing footwear of equal quality, but of different construction methods, the most common rationale, I’ve found, towards preferences in comfortability, comes down to getting the right fit for your foot, which basically comes down to the last of the shoe. Sure, aesthetics, durability and weatherproofing matters, if that’s what you’re going for, but I won’t advise anyone to sacrifice comfort and endure potential back problems or problems with your knees, your shins or your feet. For now, farewell and tread safely!