This piece comes to us from Nemanja Nikolic, the editor of Serbia’s Domino Magazine.

Heddels has already published an article about the History of Jeans Behind the Iron Curtain. But, there was another country in Europe which had special relationship with blue jeans, Yugoslavia. It was one of the many formerly communist countries, but one that held a unique position outside of the eastern bloc and away from the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence.

Yugoslavia was established as a communist state in the aftermath of WWII, but after it refused to become a satellite state to the USSR turned towards the West and initiated its own bloc of non-aligned countries comprised of the rising number of new world nations across post colonial Africa and Asia. Until its dissolution in 1991, Yugoslavia remained one of the the most modern and most approachable communist countries in Europe.

This meant that citizens were free to watch western produced movies on state TV channels and in cinemas, read foreign books, indulge in foreign magazines, listen to the latest music hits, and follow emerging art scenes of Europe and the USA without any apparent restrictions. Most importantly, citizens of Yugoslavia were free to travel to the West, in stark contrast to citizens of nearly all other communist countries who were unable to cross the Iron Curtain.

Map of the former Yugoslavia. Image via Wikimedia.

It was in this atmosphere in the 1960s that jeans arrived in Europe.

Slowly, but steadily, jeans started pouring into Yugoslavia. At first, Levi’s were worn by those who had relatives living in the West. On occasion, jeans were available for purchase in “Komision” stores where the state sold merchandise seized from the smugglers by customs control. These goods, however, came at very high prices.

Still, everything was much more complicated than in the rest of western Europe. Yugoslavia and its western neighbor, Italy, maintained a special relationship. In 1954 the two governments signed numerous bilateral agreements that allowed for closer cooperation and mutual visitation rights for citizens of Yugoslavia and Italy. In a short while, millions of people started crossing the border.

Image of Yugoslav teen wearing jeans in the 1975 tv program “Grlom u Jagode”.

During his visit in 1965, Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro described the border with Yugoslavia as one of the most open in the world.

The Italian city closest to the border was Trieste and it became the top destination of Yugoslavs, but Italians were likewise also visiting Yugoslavia, whether it was for holidays, or to buy cheap wine and cheese.

For citizens of Yugoslavia, Trieste was the nearest showroom of everything unavailable on their side of the border: shops, wealth, and the one symbol of the West that stood above all others–blue jeans.

In the early 60s, Italian entrepreneurs saw the opportunity and opened a flea market in Ponte Rosso square specifically for Yugoslavs. Thousands traveled every weekend to Ponte Rosso for shopping but back home, Yugoslavian customs only allowed the import of up to two pairs of jeans and a couple of kilos of coffee. Many tried their luck at smuggling past the state imposed limitation.

The Ponte Rosso market in 1960s Trieste, Italy. Image via Slavenka Drakulic.

Men would dress as many pairs as possible layered over each other, and girls would dress them under wide skirts. The ban was not in place for ideological considerations as one might think, but rather economic ones. Yugoslavia was always short on foreign currency, and so citizens were constrained by customs regulations for how much foreign currency they could have and thus buy foreign goods.

Levi’s, Wrangler, and Lee were everyone’s top choices, but there were also Italian brands that popped up to meet demand. One such was Rifle Jeans, the cheapest and very likely the best selling jeans in Trieste. Rifle confirmed that at the peak of its popularity during the late 1970s they were producing 50,000 pairs per day.

A vintage pair of Rifle Jeans via Etsy.

Rifle was so popular that its brand name became synonymous with the concept of jeans. Many would just colloquially reference Rifle, and ask for “Rifle Levi’s” as an example. That term remained in some Eastern European countries until today.

According to some contemporary estimates, more than 3 million pairs of jeans sold annually in Trieste stores. The vast majority of them ended up in Yugoslavia, but also other countries behind the Iron Curtain through smugglers who carried them over from there.

Blue jeans has marked an entire generation of Yugoslavs, with jeans featuring in many novels, movies, and songs. The quest for jeans also initiated travel beyond Italy to farther countries of Western Europe and forged closer ties of Yugoslavia and the West. A 1975 episode of the Yugoslav tv show “Grlom u Jagode” (below) depicts teenagers shrinking their jeans in the tub and scuffing them up to achieve a worn in look.

But despite their popularity, jeans in Yugoslavia were long seen as subversive and decadent element from the West. They were strictly forbidden in schools for many years.

The young communist activists maintained patrols in the streets of some cities, preventing youth from wearing tight jeans and cutting their jeans with razors, often causing intentional injuries along the way.

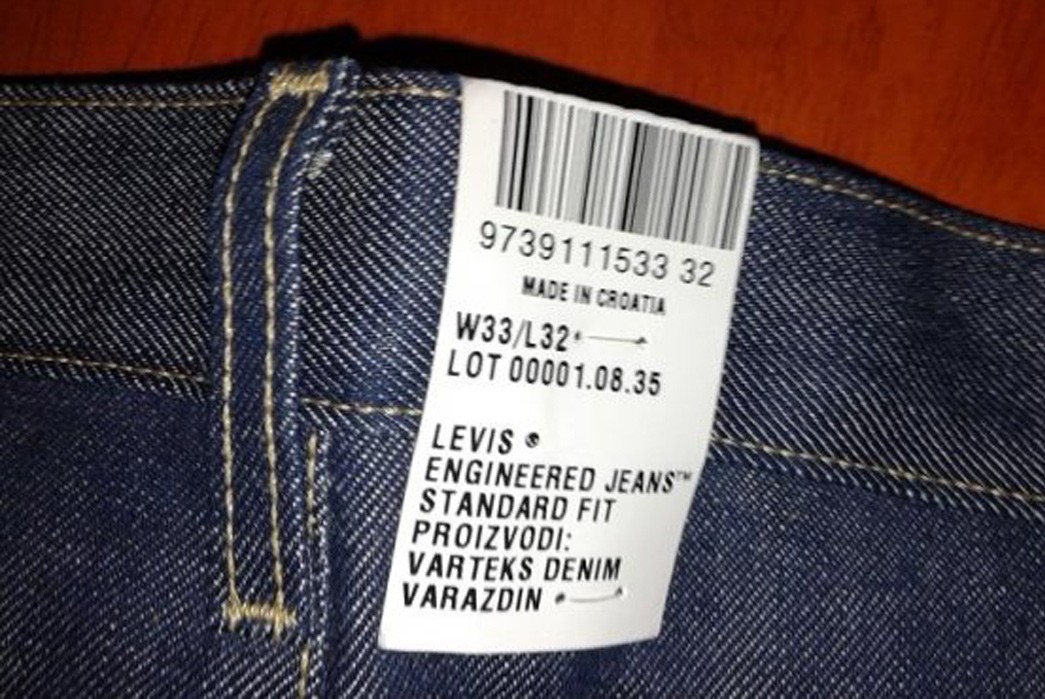

But the influence continued to grow, and in 1983, the state run corporation Varteks from Varaždin (now in Croatia) began manufacturing Levi’s under license by Levi Strauss & Co. The production began in 1984 and many proud owners claimed that these particular jeans were the best they ever owned. Better than Italian counterparts!

Everyone was able to buy the original 501 in their home country, years before the rest of Eastern Europe.

Varazdin Levi’s produced in Croatia.

Today, quality jeans can be bought everywhere, but going to the West for shopping remained a part of the culture in countries of the former Yugoslavia, even if the concept of west has shifted to include countries of the former eastern bloc, such as Hungary or Romania.

There is one more interesting effect of shopping in Trieste. Quite soon Italian “entrepreneurs” started producing and selling counterfeited jeans in the black market. It was probably the very first experience with faked goods for Eastern European consumers.

That served as inspiration for launching of a similar “business model”, in particular in the city of Novi Pazar, Serbia. By 1990’s there were hundreds of small factories that were producing fake Levi’s. Today, many of these factories still exist and continue producing high quality jeans under their labels.