“Cotton kills.” If you’re serious about hiking, trail running, or any kind of serious mountaineering, you will have undoubtedly heard this term during your search for the best gear for your outdoor endeavors. In general terms, “cotton kills” is a massive sweeping statement. But in the world of hiking and outdoor sports where temperatures can plummet drastically, cotton can kill you.

Scary right? Well, fear not. We’re diving into how cotton can kill you in cold, wet climates, and introducing some moisture-wicking alternatives.

How Cotton Kills

Image via Wikipedia

The saying ‘cotton kills’ emerged was coined in the wake of tragic stories of hikers who have died or been hospitalized as a result of wearing inadequate clothing in the outdoors. In many cases, the victims shared one common denominator: cotton clothing.

Clothing keeps you warm by trapping warm air near your skin in microscopic pockets of the fabric. However, when cotton gets wet, it ceases to insulate you because all of these air pockets fill up with water.

When you perform a vigorous activity like hiking or trail running, you sweat, and any cotton touching your skin will absorb your sweat like a sponge. Add rainfall or heavy mist into the equation and this problem is magnified tenfold.

If the air outside is colder than your body temperature, you begin to feel cold because your cotton clothing is saturated in sweat or water, thus no longer providing any insulation. This can lead to disorientation, hypothermia, and potentially death if you become too cold for too long.

Hypothermia can even occur in temperatures well above freezing and become life-threatening if you get wet and chilled at the same time.

What Is Wicking and Why Does It Matter?

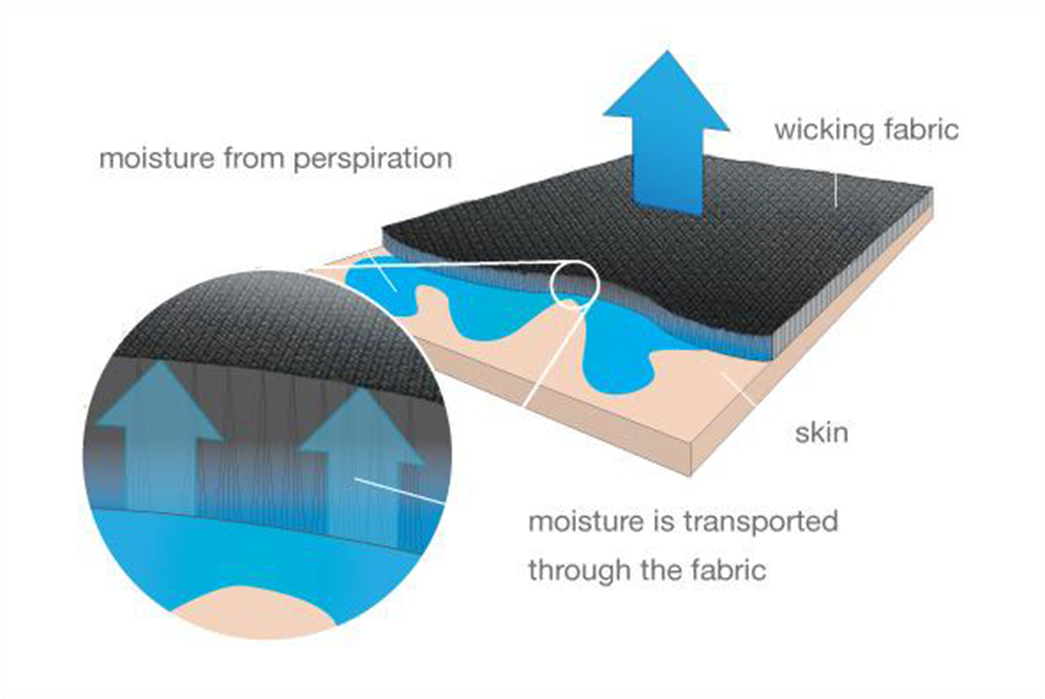

Wicking is when a material moves water from wet areas to dry areas through a process known as capillary action. Capillary action is the movement of a liquid (i.e. sweat), through tiny spaces within a fabric, due to molecular forces between the liquid and the fabric’s internal surfaces.

The layer touching the skin will move the moisture from the surface of the skin to the outer layers, leaving the part that touches the skin dry. Essentially, sweat and other moisture is pulled from away from the skin and pushed to the outside face of the fabric, where it can evaporate faster.

Imager via Olorun Sports

In the context of ‘cotton kills’ and generally keeping dry, wicking matters because it is exactly what cotton cannot do. When cotton gets wet, it stays wet.

Wicking allows materials to not get saturated by moisture it comes into contact with. Cotton garments can absorb up to 27 times their weight in water, something which means they also take forever to dry out.

Moisture Wicking Materials

Image via Aphrodite Clothing

Synthetics (polypropylene, nylon, polyester, etc.)

Synthetic fibers are “hydrophobic,” which means they resist the penetration of water. At a minimum, that means materials made from them will dry more quickly than cotton.

Most garments made from polyester or nylon are designed to insulate the body while wet by retaining trapped air. Many synthetics are designed to actively shed moisture through the shape or arrangement of their man-made fibers.

Wool

Wool, especially Melton wool, is considerably better at wicking than cotton. Wool does absorb a small amount of liquid into the core of its fibers, but it also wicks moisture out through small openings within the fabric.

Due to the fuzzy nature of wool fabrics, rain droplets are less likely to break up, instead, they ‘bead’ on the surface and run off.

A Quick Word On Layering

Layering different fabrics is widely accepted as an effective method of staying cool and dry while hiking.

For example, a wicking baselayer shirt will move moisture from the surface of your skin to the outer layers of your shirt leaving the part of the fabric touching your skin dry. The moisture is then free to move through the other layers you are wearing, such as a polyester fleece, and then an outer shell jacket.

Hopefully this clears up any confusion you might have had regarding cotton as a suitable mountaineering material and perhaps helped you reconsider your kit before your next outdoor outing.